When All Else Fails, So Does Quake Alert

The electronic alarm that alerts Caltech seismologists to a major earthquake broke down with the first jolt at 7:42 Thursday morning.

“It didn’t work for the main show!” said senior seismologist Kate Hutton, who heads the list of scientists to be notified of earthquakes over Magnitude 4 on the Richter scale. Thursday’s quake was 100 times stronger than that--6.0 on the scale, where an increase of one magnitude represents 10 times as much ground motion recorded on seismographs.

In this case, the scientists, whose pagers are connected to the alarm, got the message the same way everyone else did: They felt it.

Well Prepared

The first of several earthquake casualties at Caltech, the malfunctioning alarm only served to show how well-prepared scientists can perform despite breakdowns.

Less than two hours after the quake, the ground floor of Millikan Library was filled with reporters and news photographers.

Answering their questions was a team of experts--Hutton; Don Anderson, director of Caltech’s seismology laboratory; Lucy Jones of the U. S. Geological Survey; Clarence Allen, a geology professor; Paul Jennings, chairman of the engineering and applied sciences department, and Michael Guerin, coordinator for State Emergency Services.

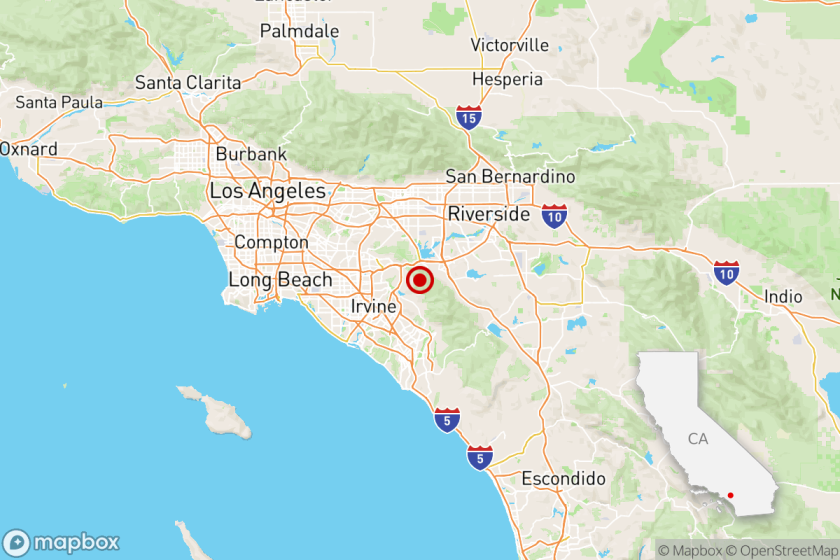

Maps Showed Fault

Performing just as they would if called upon to discuss an earthquake anywhere else in the world, they dispensed a wide variety of information, including maps that pointed out the underground fault in the Whittier Narrows area that was suspected of causing Thursday’s quake.

The scientists’ smooth operation belied the fact that the building housing the seismology lab had been ordered evacuated just after the quake, when it was most needed.

The building, Mudd South, holds sensitive seismology instruments on the second floor and a geochemical laboratory in the basement. The quake ruptured a basement pipeline carrying hazardous chemicals.

For an hour, the secretarial staff that serves as communications personnel for the seismology department stood outside while the spill was cleaned up.

Hutton said she and several others stayed in their lab anyway.

Thursday’s earthquake jolted the seismology instruments so that they could not accurately record the quake. (Some of the information released to the media came from outside sources, such as UC Berkeley.) And the computer that digests information from 260 seismic substations throughout California was overloaded, delaying for several hours the signals that come by telephone and microwave lines.

At 7:42 a.m., Hutton had just finished her early morning workout at the Caltech gym. Jones was driving from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory Child Care Center, where she had dropped off her son.

“I thought my steering went out,” she said. “If you can feel an earthquake in your car, it’s big.”

Jennings left the press conference as soon as he could to check possible damage to his house in Altadena.

The team of earthquake experts, which varies in number and composition but always represents several fields of study, last assembled in July, 1986, to discuss earthquakes that occurred within a few days in Oceanside, Palm Springs and Bishop.

During the 10 years Hutton has worked at Caltech, the team has informed the media about earthquakes all over the world.

Southern California became an earthquake study center in 1922, when the Carnegie Institute financed the first measuring devices in Pasadena and on Mt. Wilson. Caltech built its seismological lab in 1937, headed jointly by Harry Wood of the Carnegie Institute and Beno Gutenberg, a Caltech professor. New instruments have continually been added to the network they founded.

Charles Richter, who spent his entire career at Caltech and retired in 1970, worked with Gutenberg in the 1930s to devise a way to grade earthquake sizes. His name is used for the internationally known logarithmic scale that the two men created. Richter’s dedication to seismology helped make Caltech a center of earthquake study, several school spokesmen said.

“Caltech is absolutely without doubt the earthquake center of the world,” said Robert Finn, a science writer for the school.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.