Caltrans Out Front on Quake-Safe Bridges : Seismic safety: Shaken by the collapse of roadways in the Bay Area quake, it has undertaken an unparalleled retrofitting program.

Jim Roberts, a gruff-talking engineer who is happiest poring over bridge designs and calculating stress and load factors, has been thrust by the Loma Prieta earthquake into the unlikely role of an international celebrity.

Since the Oct. 17, 1989, collapse of the upper deck of Oakland’s Nimitz Freeway, engineers and seismic experts from Soviet Armenia, Japan, France, Italy, Australia and New Zealand have made pilgrimages to California to trade information with Roberts and his engineering team in the structures division of the California Department of Transportation on their favorite topic--seismic retrofitting of highway bridges.

An appreciation of the subject may elude most people, but in earthquake engineering circles California offers the latest in the design of seismic safety devices for existing bridges.

In the year since the Loma Prieta temblor showed California that its bridges were not earthquake-proof, Caltrans has embarked on a seismic safety program for bridges unparalleled in the world.

Shaken out of what officials admit was complacency, state officials have approved more than $50 million for seismic bridge projects--roughly the same amount they spent on seismic safety in the previous 17 years. The Legislature has demanded that every bridge, freeway connector, overpass or other type of elevated road structure in California be examined for earthquake vulnerability. It has mandated that any roadway deemed a possible earthquake risk be placed on a priority list for seismic retrofitting and that all of it be completed by 1994.

So far, Caltrans has identified 6,862 state bridges as potential candidates for seismic retrofitting. Officials believe that further analysis will pare down the list to about 4,800. Another 6,792 locally maintained bridges are expected to be added to the retrofit program. Before it is over, officials estimate that the retrofitting may cost between $1 billion and $2 billion, a far cry from their original guesses of between $300 million and $500 million.

“We’re in a mandated crash program and right in the middle of that mandated crash program we are developing, experimenting with, learning and applying stuff that hasn’t been done any place in the world,” said Caltrans Director Robert K. Best. “We’re doing things here in California during the last year that have never been done any place in terms of earthquake research and evaluation.”

In the 15 seconds that the Loma Prieta earthquake shook Northern California, it did more to change Caltrans than any single event. The collapse of a milelong stretch of the Cypress viaduct section of the Nimitz killed 42 people and exposed critical flaws in a seismic retrofitting program that had been considered a national model.

George Housner, a retired Caltech professor who headed a board of inquiry appointed by Gov. George Deukmejian to investigate the collapse, said the disaster showed that seismic retrofitting could no longer be treated as an afterthought in the transportation budget-making process or permitted to proceed at a snail’s pace. Nor, he said, could engineers use past experience as their sole guide for designing seismic protections for bridges.

“If you put it (the Nimitz collapse) in the context of the total deaths and injuries that occurred in transportation-related accidents in California every year, it looks pretty small,” said Best. “But it’s a single, very spectacular event and because of that it has created a dedication both with the department and with the policy-makers of state government that we’re going to make damn sure it doesn’t happen again.”

From its inception 17 years ago, the retrofitting program has been driven by earthquakes. Each time a temblor strikes California and cripples highway bridges, engineers rush in to assess the cause of the damage and develop techniques for strengthening similar structures.

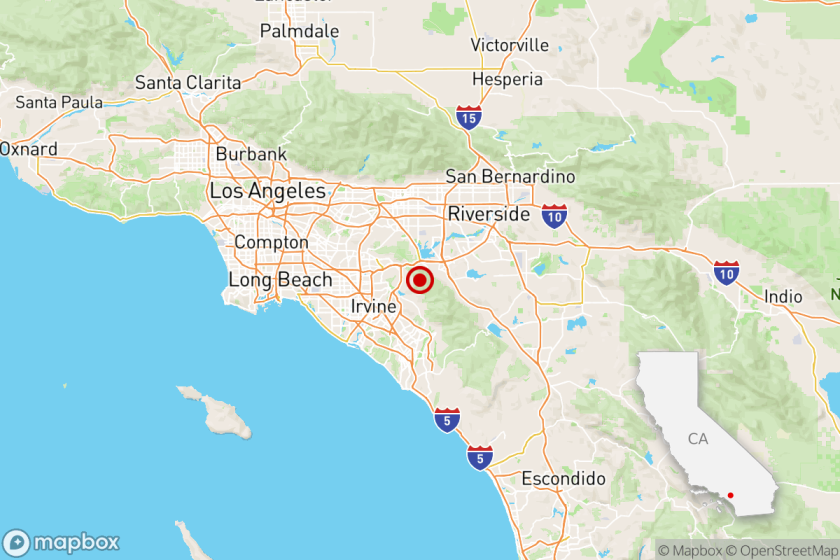

After the 1971 Sylmar quake collapsed part of the I-5 and I-210 interchange, Caltrans launched a retrofitting program of reinforcing bridge spans by tying roadway sections together and mooring them to support columns to prevent slipping during intense shaking. After the October, 1987, Whittier quake, Caltrans turned its attention to the columns that support bridge decks and began designing ways that they could be buttressed to prevent crumbling under extraordinary stress.

The two quakes together only caused two highway deaths, and seismic retrofitting took a back seat to other road programs in the budget-making process.

“When the 1971 and the 1987 quakes occurred there was tremendous focus and rhetoric and a lot of promises immediately after the quakes, but as time went on seismic upgrading became less and less of a priority,” said Assembly Transportation Committee Chairman Richard Katz (D-Sylmar).

Housner credits Roberts’ engineers for always being “willing to do a good job,” but said that in the past they were often “cut back because somebody else felt they had more urgent need for the money.”

Then came the Loma Prieta earthquake and the death toll was not two but 44, the Bay Area highway damage not a few million but nearly $1 billion. Within weeks, the Legislature elevated the seismic retrofitting program to top priority in the department.

“As of right now, the environment has changed definitely because we now have a law that essentially says earthquake retrofit is the No. 1 priority for the expenditure of funds in the state,” said Best.

Housner said the new funding priority forced the department practically overnight to change its fundamental mind-set. Expanding highway capacity became secondary to ensuring the safety of those that existed.

“California has always been sort of a leader in earthquake engineering but Caltrans has just sort of put the blinders on,” said Housner. “(Caltrans) had such a big building program they were turning out a bridge a day for years. Their main thought was how to build bridges efficiently and rapidly. Retrofitting was a low priority.”

After Housner’s committee issued its recommendations it was determined that Caltrans would not only have to develop techniques to protect bridges from the type of damage created by the Loma Prieta quake, but it would have to predict what might happen to bridges in future quakes.

With supercomputers and new techniques, Best said, the department could simulate different kinds of quakes and determine how individual structures would react to them.

“Now that’s a tremendous advancement away from the days of saying, ‘Well, we saw this happen, now how can we stop that from recurring?’ to sitting back and predicting things that we’ve never seen before and then designing ways to stop them from happening,” Best said.

He said the department is aiming at a retrofitting standard that would set the survival probability at 99.99%.

“You talk about change,” Best said. “We are so far ahead of almost everybody else in terms of seismic design and retrofitting of transportation structures that there is nobody to turn to. We’re just developing everything as we’re going along.”

Before the quake the department retrofit program employed just a few engineers and contractors; now at least 500 people work in one aspect or another of seismic retrofitting. Because of the retrofitting and accelerated highway construction programs, each year Caltrans is recruiting and hiring one-third of all civil engineering graduates in the United States.

To assist in the development of techniques for retrofitting bridges, it has awarded nearly $8 million in research contracts in the last year to the University of California campuses at Irvine, San Diego, Berkeley and Davis; USC, the University of Nevada at Reno and two private consulting firms.

“One thing I think will make a big difference in the future is that they now are appointing some earthquake advisory committees that include outside experts,” said Housner. “Before they were sort of inbred. They were not asking for any comments from outside so they fell behind on some of the earthquake engineering part of it.”

California’s crash program is not without its potential aftershocks. State government has only begun to pay the bill for the massive retrofitting projects. The engineering and design work of the early months was relatively inexpensive; the real costs will come in a few years when some of the bigger projects get under way.

“As you go on you start spending more and more money. That will be the test. Whether in a couple of years from now as the bills begin to mount it is still a crash program, full speed ahead, costs be damned, or whether the program is leveled out and those funds are distributed over more years,” Best said.

Initially, $80 million from a temporary quarter-cent sales tax was earmarked for bridge retrofitting. The state Department of Finance has indicated that another $300 million from the special sales tax may also be slated for earthquake retrofit work. The Federal Highway Administration has made funds available for the replacement of structures damaged or destroyed by the quake but has ruled that other retrofit programs are not eligible for federal disaster relief funds.

Once the initial funding is used up, Katz said, the department will have to begin using money from a gasoline tax increase that was approved by voters in June. Although it was originally determined that some revenue from the tax increase would be used for seismic work, it was never contemplated that the “final price tag” would be over $1 billion, Katz said.

Katz recently held a legislative hearing to examine the costs of the retrofitting program. He said the purpose of the hearing was twofold. He wanted to put Caltrans on notice that lawmakers were not going to back off from their decision to make seismic retrofitting the agency’s top priority. At the same time, he said, he wanted it known that they would be watching expenditures.

“Part of our purpose was to let Caltrans know we’re not going away,” said Katz. “The commitment I made was that seismic retrofitting is going to be high priority. I will honor that commitment even if it means some new project for new capacity is delayed. We have an obligation to make the existing roadways safe before we build new roadways.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.