He’s Got the Beat

Want to know the secret of the drummer who’s played on more rock, pop, R&B; and blues hits than any other? Learn to dance.

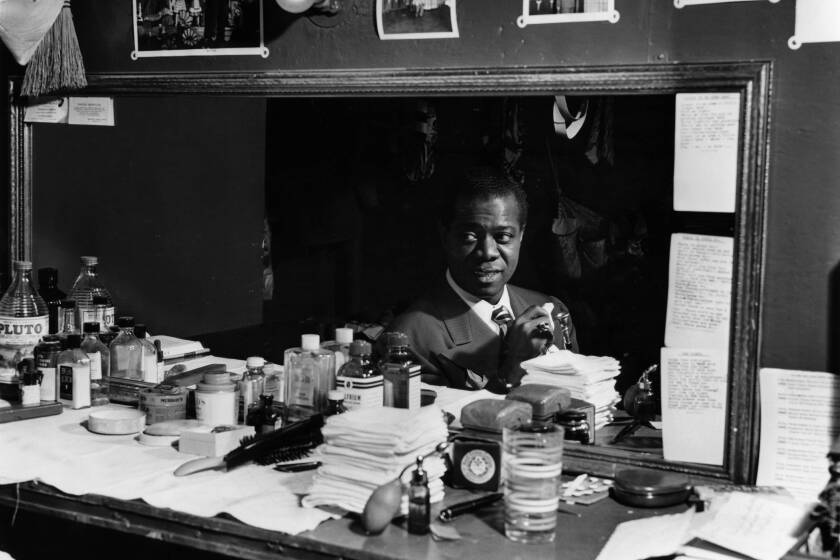

Earl Palmer, among the first batch of key musicians of the rock era inducted last month into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in a new Sidemen category, is widely cited as the most recorded drummer in rock history.

He started in New Orleans playing jazz. Then as R&B;, blues, jazz and country began to coalesce into something new in the late ‘40s and early ‘50s, Palmer helped define the beat that would become rock on hundreds of early records by Fats Domino, Little Richard and others great and small.

After moving to Los Angeles in the late ‘50s, Palmer played in thousands more sessions, not only behind countless rock performers but also for hundreds of movies, TV shows and commercials.

And he credits it all to learning to dance as a kid.

“When I grew up in New Orleans, I wasn’t playing music, I was a tap dancer with my mother in vaudeville,” Palmer, 75, said by phone recently from his home in Pacoima. “I was in vaudeville since I was 5 years old.

“I played drums a little as a kid, but I didn’t start playing music formally until I got out of the service in 1945. I think I was successful because [through] tap dancing, I got to learn about syncopation, rhythm and know the structure of a song from dancing to them,” said Palmer, who plays at Abilene Rose in Fountain Valley as part of a new Sunday jazz series at the club.

“The other thing I have from being a dancer is being able to do a little of everything”--meaning singing, dancing and playing different instruments.

As was the case with many of the musicians who developed the sound of rock, Palmer didn’t recognize at the time that he was helping create a new style of music.

“We didn’t know what we were playing was going to be rock ‘n’ roll’s great classic hits,” he said. “Like every other kid, I just grew up playing the music where I was from, which was jazz. We were trying to play like Miles Davis and Max Roach and Charlie Parker.”

The melting pot that is New Orleans contributed to the flexibility that over the years has enabled Palmer to shift from sessions with Pat Boone and Professor Longhair in the ‘50s to Sam Cooke, Phil Spector and the Monkees in the ‘60s to Tom Waits in the ‘70s and Elvis Costello in the ‘80s.

“People living in New Orleans just like music, period,” Palmer said. “They like something they can shake their fannies to and pat their feet to. New Orleans people have their own music that has tinges of this and tinges of that in it.

“So what we were playing on those early records was funky in relation to jazz,” he said. “What we were playing already had that natural New Orleans flavor about the music. I played the bass drum how they played bass drum in funeral parade bands. I had to do something to make it funky.”

Making it up as they went was one of the defining concepts of rock ‘n’ roll.

“This kind of music is almost totally creative,” Palmer said. “We had no [written] music for those things--the music was learned and it was up to the musicians to add to it. A lot of it came from the musicians.”

Because of the spontaneous, improvisatory nature of rock music, many onlookers assumed the musicians were untrained. And while many star performers could neither read nor write music, the same wasn’t necessarily true of the players working with them.

“I went to music school on the GI bill,” Palmer said. “I minored in drums and that’s where I learned how to read music. I took theory and harmony, and actually was a piano major, though I never really played it much. I studied arranging and composition.”

At the outset of rock, however, New York and Los Angeles--and to a lesser extent Chicago and Dallas--not New Orleans, were where the most studio activity was going on, and hence where the most money was to be made. So Palmer decided to head west.

“I knew I was never going to be a Buddy Rich--a great soloist. That’s why I went to music school. I wanted to learn about arranging,” he said. “I came to work [in Los Angeles] for Latin Records to do arranging and producing. What stood me in good stead was being able to come and work as a producer and arranger.”

With his reputation preceding him as a drummer on those early rock hits out of New Orleans, he quickly found as much demand for his instrumental services in L.A. as back home.

Palmer said he came to appreciate a camaraderie among West Coast studio players.

“When some of those guys would come out from New York, they brought that New York animosity with them,” he said. “But we were always helpful to people doing those sessions. . . . That was some of the most fun: playing with guys who, if you were a little better than some, you never felt that you were so much better than anybody. It was always refreshing to go to work.”

That, he said, made it easier to bring freshness to whatever he was called upon to play--whether a wall-of-sound pop session with legendary producer Spector or the theme to a TV show or movie--no matter how many times he might have to play the same piece.

“They don’t want you saying ‘I’m tired.’ You have to bring yourself up every time, and lock into a way to do it every time with something interesting, yet without totally changing it,” said Palmer, who still plays club dates as often as he can. “You always want it to sound like it’s the first time the musicians have heard the music, that it has all the fire of playing it the first time.”

BE THERE

Earl Palmer plays Sunday at Abilene Rose, 10830 Warner Ave., Fountain Valley. $8 to $10. 6:30 p.m. (714) 963-1700.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.