Jazz Life Gets a Bit Less Blue

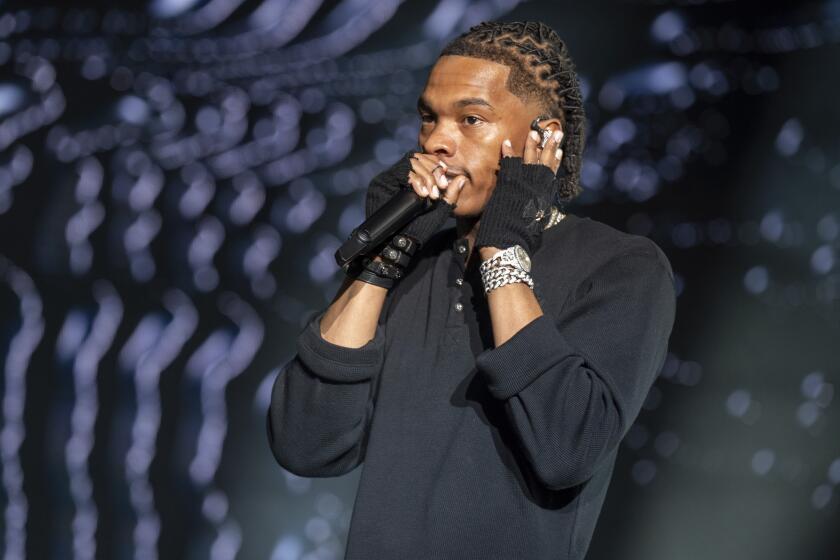

He lived through the days when gigs were nowhere to be found, when he was thankful to play for pennies. He flipped burgers and stocked the shelves at Kmart to pay the grocery bills. But Mitchell Player couldn’t lay his bass down, not for anything. Jazz was an infection he couldn’t shake.

He plays New Orleans, a town thick with the tales of music and hunger, music and racial oppression, music and slavery, music and death. Look what’s left when the lore is peeled back, when the tourists go home: hundreds of men and women trying to keep it together, moonlighting and divorcing and struggling to pay the landlord but holding their heads up, baby, because they’re not in it for creature comforts.

Now, for the first time, New Orleans is trying to give a little help to the hundreds of struggling musicians who haunt these streets. This summer, the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Foundation, local banks and the city agreed to sponsor a $1.5-million program to grant low-interest housing loans to working artists--people whose income has traditionally been considered too erratic for loan payments. At the same time, a three-year-old musicians’ clinic offers deeply discounted medical, dental and psychiatric care.

The specter of the starving artist is nothing new. But this is the cradle of jazz, the heart of indigenous American music. New Orleans beckons visitors from every continent with its banquet of sound, its zydeco and Cajun, its blues and gospel and swamp pop and, of course, its jazz. Undaunted by dank fogs and slamming heat, the tourists swarm to the Louisiana swamps to hear the music and to join the famed jamborees.

“They’re realizing what our talent means for business,” says Player, who hopes to buy himself a small house. “I mean, what do you think New Orleans would do if there were no musicians here? What would there be? People don’t think about how we’re living.”

The programs are a small start: Songsters still live hard and die poor in the classic New Orleans vie boheme. But the health and housing initiatives mark a new consciousness, the novel notion that New Orleans should pony up a little money for its beloved music. As a matter of sheer ethics, musicians argue, the community should invest in the artists who lure the tourists.

“The awareness of the value of the music is rising slowly in this community, but at least it’s beginning to rise,” says Harold Battiste, a saxophonist and producer who teaches in the University of New Orleans jazz studies program.

“It’s difficult when it’s in your backyard. People pass by and say, ‘Look what you got.’ And you say, ‘Aw, that ain’t nothing but junk.’ ”

The night clings to the skin in the stone tunnel that opens into Preservation Hall. This is jazz stripped, sweating and unapologetic in the feeble light of bare bulbs. No beer for sale and no air-conditioning.

The tourists crouch on benches in the shadows along the wall or curl Indian-style on the floorboards. Having paid their $5, they wait in their straw hats and diamond rings. They straighten up and clap like children when Player swings in off the street, wheeling his bass before him.

Out in the garden, Tom Ebbert sips at his Coca-Cola, waiting for showtime. He’s 81, and in the long years of late nights and worried days, he’s grown to resemble his trombone--thin as brass pipes, rounded and stooped at every angle.

“You know what they call a trombone player with a business card?”

Trembling fingers pull one from a cracked, creased billfold.

“An optimist.”

A scrawny cat slips from the shadow of a banana tree, winds around Ebbert’s shoes. The wrinkled musician doesn’t take notice. He grew up in Pittsburgh, Ebbert did, and picked up the trombone in the eighth grade. He’s been living behind the brass bell ever since.

He came to the swamp in the late 1960s, lured by the promise of a steady gig. Work or none, he’s been here ever since. He tried Las Vegas once, only to fall on tight times. He bumped north and south, crossed the country on dark interstates, dozing in buses and cars. He went to Los Angeles and worked a factory job.

He got bored. He came back. He couldn’t stay off the stage. Hooked on jazz and he doesn’t even think he’s all that talented.

“I’ve played beside very good musicians before,” Ebbert says. “That’s when I found out I was mediocre.”

But he keeps blowing, keeps sliding, arm still spry. For all the hard and hungry times, the days he wondered if he should pack it in, Ebbert is still plugging away.

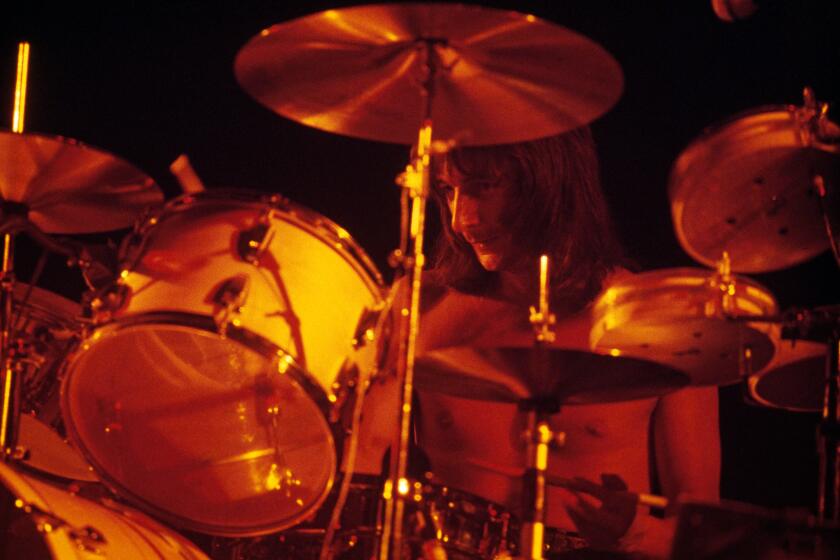

“I’m hard of hearing,” he shrugs, tugging at an earlobe. “Sitting in front of drummers all my life.” After the first set, he’ll be too tired to talk. Behind him, the tourists stomp in from the flashing caverns of the French Quarter.

It’s 8:30 p.m. The night is just beginning to crack open and run, warm and liquid over the antique rooftops.

These days, if he’s quick and clever, a New Orleans musician can make a living--just--from the music. Player plucks his steel strings on the steamboats of the Mississippi River. He plays Sunday brunches and in the famed old clubs of the French Quarter, where jazz is as organic as sweat and the simmer of red beans and ham hock.

Not so long ago, he was a high school football player from Shreveport who pondered law school. But at Grambling State University, the music kept tugging. Finally, he gave in, dropped out and drove the steamy Southern pilgrimage.

“All the cats were in New Orleans,” he says.

At 30, Player does pretty well: On a very good year, he figures he pockets about $30,000 in spurts and chunks. It’s enough to get by, enough to raise his son. Trouble is, random cash windfalls don’t exactly light up the eyes of a loan officer.

“They want to see regular employment,” Player says. “It just doesn’t work that way for a jazz musician. You do a gig here, do a gig there.”

That’s where the housing program comes in. Player is one of the artists applying for a loan and mortgage from the jazz foundation. To qualify, he’ll have to log 12 hours of classes in homeownership and money management.

The jazz foundation will put up money for down payments, and local banks have agreed to set up the mortgages and help the artists renovate blighted homes. Musicians can soften their monthly payments by borrowing money from the city--debts that will be dropped if the artist lives in his new home for a decade. Eventually, the program could provide as many as 20 houses a year, says jazz foundation program director Sharon Martin.

“We’ll hang in with them,” she says, “as long as it takes.”

Martin knows the bumps of a musician’s life. She too is wearing herself weary on song, heading to the clubs after work to sing her nights away.

“These are not regular get-a-check-every-month workers,” she says. “They are out there pumping away, day after day. And we need to help them out, to make sure they can stay here.”

“You hear about them and you think, ‘Oh, there goes another one,’ ” says disc jockey Judy Wood. She’s in the studios at WWOZ, in the heart of the Treme, one of the nation’s oldest black neighborhoods. Slanting over the cramped streets, a late afternoon sun throws stripes of shadow on shelves of dog-eared albums.

“Remember Ed Frank?” broods station programmer Michael Gourrier. “Then Johnny Adams. And who was that little sharp dude used to have that place on LaSalle?”

“Fred Kemp.”

“Fred Kemp,” Gourrier nods. “They’re dying off all the time. It’s depressing.”

Classic New Orleans axiom: There’s a funeral parlor and a bar on every block. The equation of music and death goes something like this: Funerals have their own kind of jazz--dirges--and musicians have their own sort of burials: the makeshift kind, scraped together from charity when a neglected body finally gives out.

This summer has been thick with death. Cancer took down musician and mixer Rodger Poche. Before bluesman Ernie K-Doe died earlier this month, his old friends were scraping together concerts to pay for his hospital bills. Instead, the money went to funeral costs. Timothea, a native blues songstress, has crooned in three funeral benefits in the last six weeks.

“We’ve had nobody else to raise that money, so that’s what we do,” she says. “So many of us have died on the steps of the Charity Hospital.”

It was the funerals that prodded former undertaker Johann Bultman to scrape together public and private cash to found the Musicians’ Clinic at Louisiana State University Medical Center. He’d spent years in the parlor of his family’s New Orleans funeral home.

“People were always looking for a casket to bury a dead, poor musician,” he says.

The clinic is supposed to keep an eye on the musicians before, in Gourrier’s words, they “hole up and die.” So far, 600 artists have been treated there. But sometimes it’s too late.

Timothea, 50, was aching and weary for years. Too tired, some days, to get out of bed. When she finally strolled into the clinic, she hadn’t seen a doctor in 20 years.

She had liver cancer, the doctors told her. Turned out undiagnosed hepatitis C had been festering in her veins for years.

“I was feeling bad all the while and not even knowing why,” she says. “But musicians aren’t born with silver spoons in our mouths. We don’t have any insurance; we take our chances.”

Louis Armstrong had a key to the city but never owned a piece of New Orleans dirt. Today, a wide, leafy park bears his name. But when Louisiana banned black and white musicians from sharing a stage, Armstrong stayed away for a decade.

If he’d lived, Armstrong would turn 100 Saturday--and New Orleans is decking the old balconies for yet another jazz celebration, the Satchmo SummerFest. By day, professors will expound on Armstrong’s long influence. By night, big-name musicians will blow and scat in his memory. With pomp and ceremony, the city airport will take his name.

In life, Armstrong had a tricky relationship with New Orleans, where he was born a prostitute’s son on a hardscrabble street near what is now City Hall. A young Armstrong unloaded crates of plantains on the docks, sold coal and drove a milk wagon. Finally, he headed north to make his name in Chicago and New York.

“Thank God we’re honoring him now,” says Tad Jones, a biographer researching Armstrong’s New Orleans years. “We’re finally getting to it.”

Gourrier--the WWOZ programmer, jazz foundation board member and self-described “cultural custodian,” paces Armstrong Park in the dead afternoon heat, a great ceiling of elm and oak laced above him.

“Here,” he says with a sweep of the arm, “the seeds were planted.”

The park is built around old Congo Square. There was a time when slave women came to these stones to stomp and sing away the Sundays. Their congo, calinda and bamboula dances somehow crossed the Atlantic uncrushed in the bellies of slaving ships.

“It started here and we have, shall we say, a minute memory of it,” Gourrier says.

Over time, the raw rhythms mated with strands of European tradition and the notes rang off the walls in the whorehouses of Storyville, in the benevolent society halls of the Treme. The city split open and bled jazz before the musical form had that name.

It was music that gave breath to this decrepit old sin city. It was the invisible landscape of pitch and rhythm--the one that thumps at your ribs--that Louisiana had in mind when the state tourism office picked the theme for its advertising campaigns: Music.

Tonight’s audience was urged by tourist manuals to stop by Preservation Hall, to hear “Tiger Rag” and “When the Saints Go Marchin’ In.” They yammer in Japanese and Russian and bawdy American English while the band arranges itself before them in starched shirts.

Then the snare cracks and the trombone bellows and they’re off, the music swings wild and sweet, the drum smacking at its rear. And the listeners grow quiet to tap their knees, and the faces of passersby press to the smudged old windows to hear, paused on the gaudy shuffle of St. Peter Street.

“They like the music, but what nobody sees is these artists are going hungry, without medicines, without housing, in the place where their art originated,” Gourrier says.

“We’re so proud. But we should all be embarrassed.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.