Auditors Put New Spin on Revolt Over Royalties

As fans rush to record stores for their favorite stars’ new CDs, some artists behind the music are getting themselves auditors to make sure they don’t get shortchanged by their labels.

Many musicians and their managers are seeking outside help in challenging royalty formulas and contracts that they--and a few courts--have said are denying them their fair share of the profits.

Last month, shortly before her death, torch singer Peggy Lee and as many as 300 other performers obtained a proposed $4.75-million settlement in a class-action suit that accused their record company of cheating them out of royalties dating back to the 1940s.

Before Lee, the Ronettes, a ‘60s group, won a similar judgment, as did rock singer Meat Loaf, whose music label paid him an estimated $10 million to drop his royalty suit. Other stars claiming to have been shortchanged in royalties include the Dixie Chicks, Merle Haggard, Tom Petty, John Fogerty, Don Henley, Courtney Love, Tom Waits and the estates of Billie Holiday, Patsy Cline and Buddy Holly.

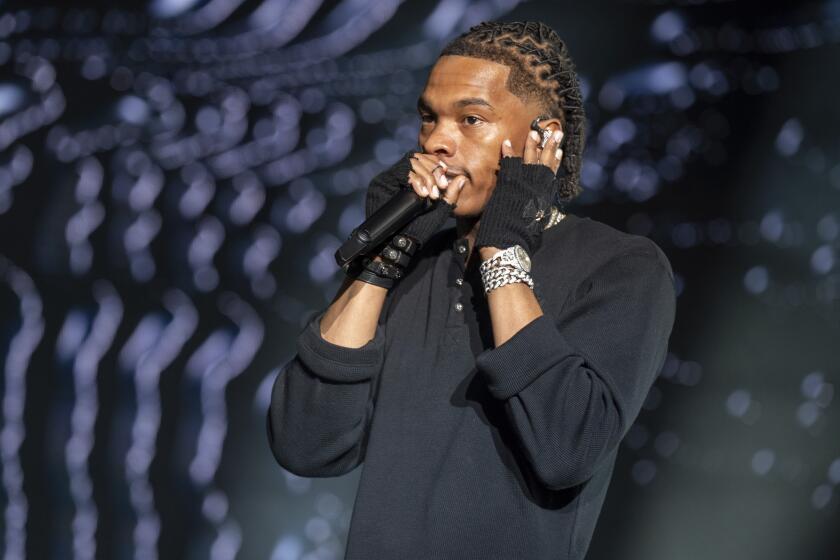

This week, as the annual Grammy Awards ceremony approaches, the war over royalties is intensifying. Tonight the Eagles, Sheryl Crow and a dozen other stars will take the stage at four sold-out benefit concerts organized by the Recording Artists Coalition to raise funds to lobby lawmakers for fairer record contracts and to clean up accounting practices.

The five major music conglomerates--Vivendi Universal, Sony, Bertelsmann, EMI and AOL Time Warner--say they pay artists accurate royalties based on time-honored industry accounting practices.

The recording labels say accounting errors have occurred unintentionally and that, on occasion, the companies have negotiated settlements simply to keep important artists happy.

Record companies say their royalty departments do not plot to cheat artists. They say they pay accurate royalties based on provisions in recording contracts, which each artist voluntarily signs. The companies contend that many of their differences with artists stem from interpretations of what the contracts specify.

“Most of the problems we detect are contractually permissible,” said Nevada accountant Phil Ames, who has been performing royalty audits for three decades. “All of these artificial deductions are embedded in the contract.”

Auditors at the dozen firms that specialize in this field say some record labels routinely fleece artists of millions in unpaid royalties.

“Record companies use questionable accounting tactics and contractual provisions to get away with unconscionable things,” said accountant Wayne Coleman, whose St. Louis firm has recovered more than $100 million in unpaid royalties for clients, including Haggard. “Of the thousands of royalty compliance audits I’ve conducted over the past 30 years, I can recall only one instance where the artist owed money to the company.”

These accounting practices are about to be scrutinized by lawmakers. State Sen. Kevin Murray (D-Culver City) plans to introduce a bill this year to penalize record labels that purposely underpay royalties--making it a crime punishable by a $100,000 fine. Murray said he expects to hold hearings in Sacramento by May.

These political moves follow lawsuits filed in the last year by Love and the Dixie Chicks against their record companies, Vivendi Universal and Sony. The suits accused the companies of engaging in “systematic thievery” to “swindle” them and other acts out of millions of dollars in royalty earnings with “corrupt” accounting practices.

The record companies deny the allegations.

Outside auditors acknowledge that some in their business submit inflated royalty claims to music companies. They also say not all record companies treat their clients unfairly or are unwilling to open their books.

“I have never had a problem with Universal and wouldn’t put them in the same category as other record companies,” said Coleman, who has done consulting for Vivendi Universal.

But others are not so generous in their assessments. They accuse all five major companies of, at times, impeding audits by refusing to turn over proper documents, an allegation the companies deny.

Auditors say they often catch music corporations overcharging artists for in-house label services and underreporting sales figures, particularly overseas. It’s not uncommon, accountants say, to uncover a 10% to 30% underpayment of royalties in an audit. And a typical audit can cost $50,000.

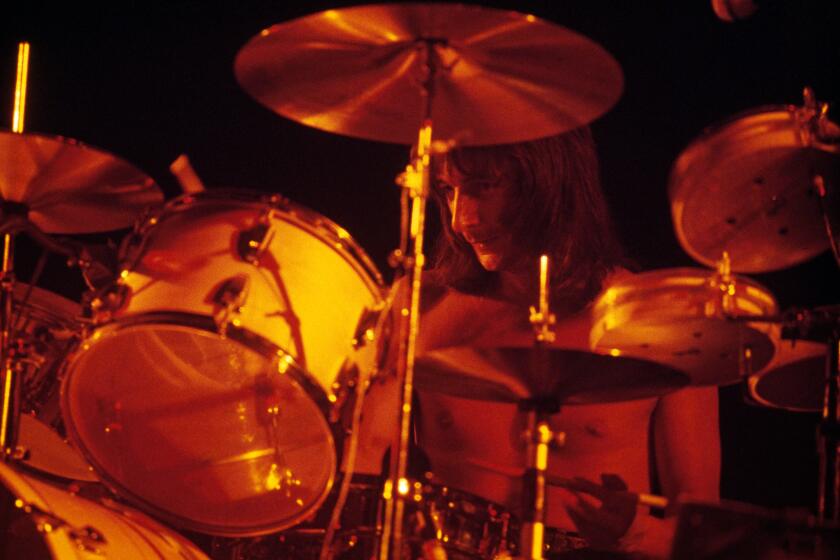

Six years ago, rock singer Meat Loaf sued Cleveland International, a small Ohio record label that signed him to a contract in 1977 and, with Sony’s Epic Records, manufactured and distributed “Bat Out of Hell,” which became one of the best-selling pop albums.

Throughout the 1980s, Meat Loaf suspected more copies of “Bat Out of Hell” were being sold than his record company acknowledged. The singer’s suspicions were confirmed in 1991 after SoundScan, an independent computerized sales tracking system, began tabulating store sales. The first week that Billboard published SoundScan charts, Meat Loaf’s 14-year-old album was in the top 50. By 1993, SoundScan had tracked 3 million sales of “Bat Out of Hell” in the U.S. alone.

Meat Loaf sued Cleveland International and Sony, alleging that its Epic division sold more than 25 million copies of the album and owed him an estimated $14 million in unpaid royalties. The case was resolved with an out-of-court settlement estimated at nearly $10 million, sources said.

Rocker Tom Petty said he routinely audits his record companies after every new release. “I personally have turned up millions of dollars missing [in royalties]--money that I would not have been paid without an audit.” Petty said he reached royalty settlements with his record companies.

Under most recording contracts, a music company does not pay royalties until it recovers funds paid to the artist to cover studio recording expenses, plus radio promotion, tour support and living expenses. The record labels also deduct for packaging and promotional giveaways before paying royalties.

The record industry prohibits auditing of crucial manufacturing and distribution documents, making it difficult to determine how many CDs are sold, bartered for radio airplay or discount-priced through record clubs. Auditors say record companies began inserting restrictive audit provisions into recording contracts in the late 1970s.

Another restriction prevents an auditor from performing more than one audit at a time per record label. Contracts typically give artists and their managers a window of only three years after the release of a record to initiate an audit.

Even after an audit, getting a record label to pay is another matter.

“The company holds my money for five years and I pay an auditor to collect it,” said Haggard, who has paid for audits of several record companies. “[My auditor] catches them cheating me out of hundreds of thousands of dollars and then the company offers to pay me half of what they owe--with no interest. What’s wrong with this picture?”

Under most contracts, if an artist catches the company failing to pay proper royalties, the musician must pay for legal expenses. And if the act wins the case, the company has 30 days to pay the royalties before an act can break its deal.

“The companies play this ‘catch-us-if-you-can’ game with artist royalties,” said Sherman Oaks accountant Fred Wolinsky. “It’s not like they sit down and scheme how to take advantage of everybody. But the systems are designed to impede. They’re archaic and the royalty staffs are lean. Only artists with muscle really have the ability to get their money.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.