A Santa Ana student’s father faced deportation. Her work to free him helped send her to Harvard

Before Cielo Echegoyén got accepted there last fall, only three Santa Ana High School students ever had been admitted to Harvard University.

For Cielo, the mileposts along her arduous journey from Orange County to Cambridge, Mass., included countless nights poring over books at the public library until closing time — it was too crowded to study at her family’s apartment — and three operations to correct a disorder called funnel chest that caused her breastbone to press against her heart and lungs.

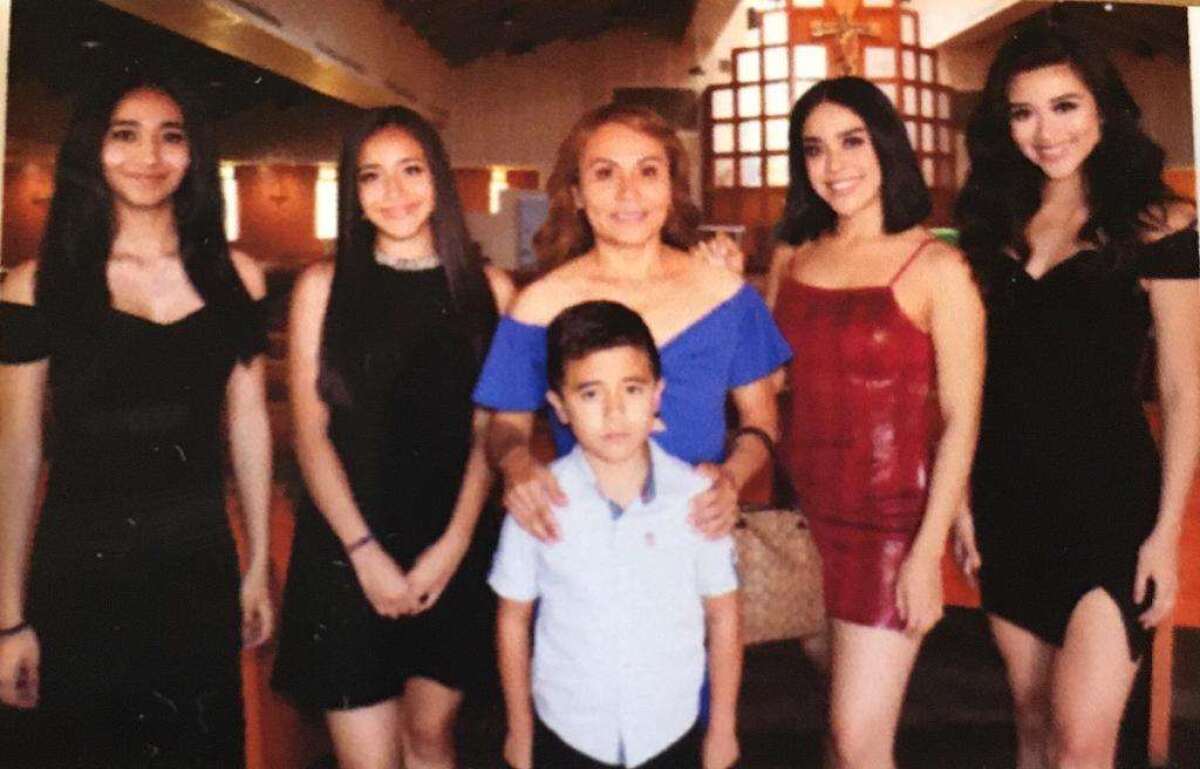

“She was falling behind in school due to her surgeries,” recalled her mother, Elvia Soriano. “But a month or two later she was at the same [academic] level as before.”

“My daughter has worked day and night to achieve this dream,” she added.

As news of Cielo’s acceptance spread, this daughter of Mexican and Salvadoran immigrants has been held up as an inspirational figure in the predominantly Latino Santa Ana Unified School District, where 87% of students come from low-income families.

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

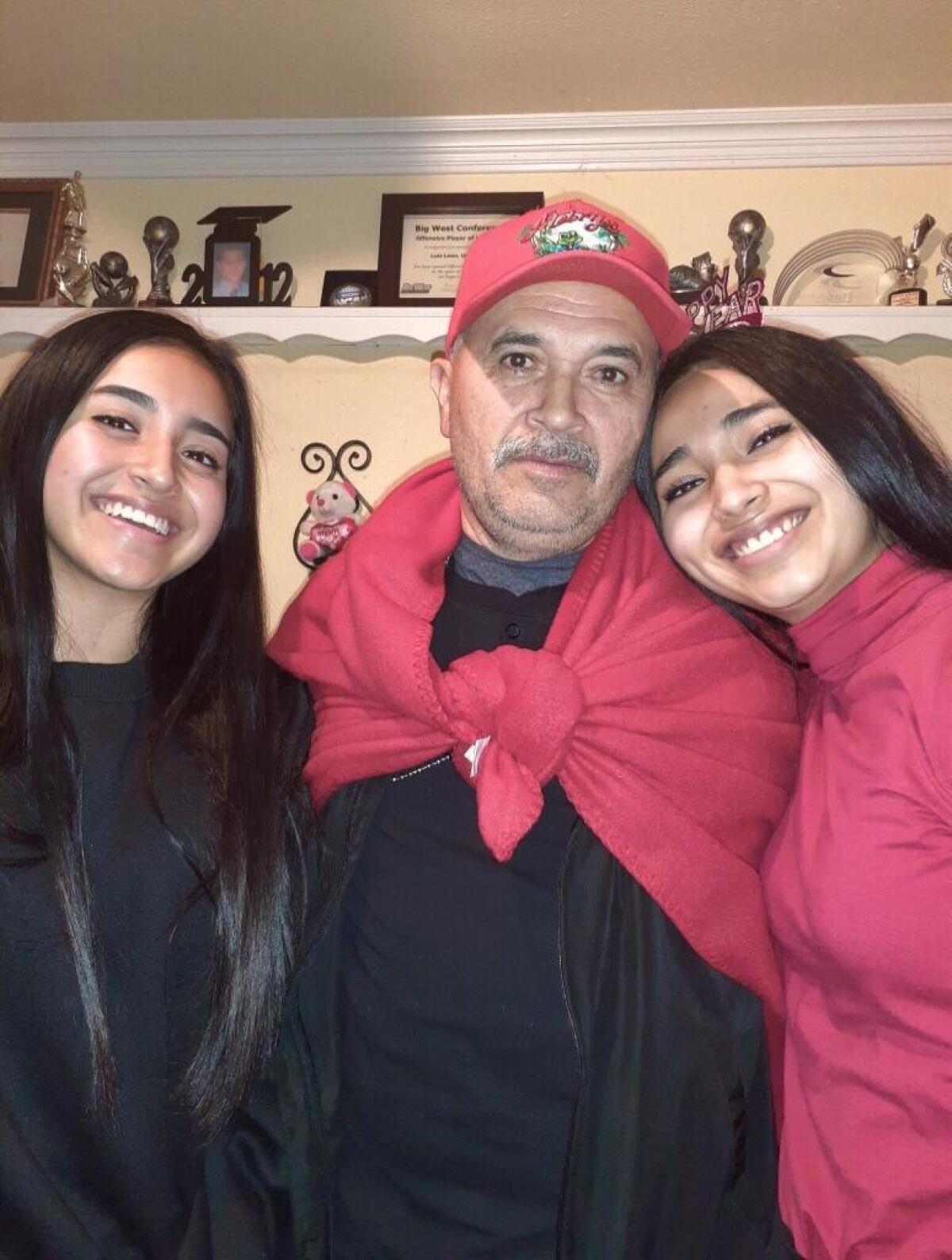

But to hear the 18-year-old Cielo tell it, her struggles paled in comparison to the travails of two men being held at an immigration detention center. She came to know the men because her father had been held there too.

“They were going through something more difficult than I was,” she said.

In a roundabout way, their detention would play a role in her admission into the Harvard class of 2025.

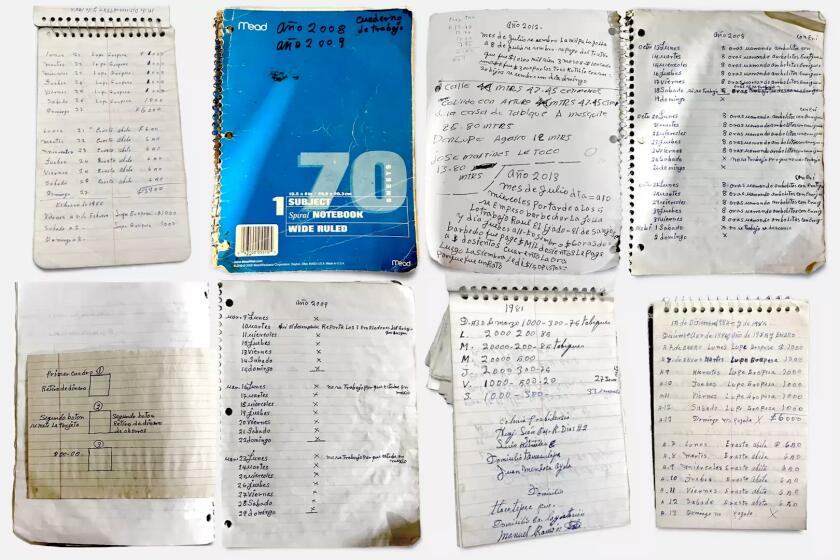

In June 2019, her father, Héctor Echegoyén, who’d been working for a local cleaning service, was detained by immigration authorities in Santa Ana while going to pick up the mail with his son, Ethan. A native of El Salvador, he had been facing a deportation order since 1994, the year he entered the United States without documents.

“My family was shocked,” Cielo said. “I was quite scared of the possibility that my father would be deported.”

For six months, while Héctor was held at the detention center, Cielo and her three sisters visited him at least once a week, driving 82 miles from Santa Ana and making authorities aware that they were watching over their father. Cielo also began to immerse herself in studying the legal complexities of his predicament, and the family sought help, retaining a pro-bono attorney from the white shoe law firm Gibson Dunn.

To raise funds for Héctor’s bail, the family drained part of its savings and then, in December 2019, started doing food sales in the courtyard of their apartment building: tacos, pozole, flan and cheesecake. Later they went door to door offering their wares.

“I knew that the quicker we raised those funds, the quicker my dad was going to be able to get home,” Cielo said. Eventually, the family pulled together $30,000.

In the months since her father was released on bail in December 2019, he has been prohibited from working; his wife, Soriano, works for a parachute manufacturer. He is scheduled for a hearing in October, when he plans to request that his deportation order be suspended.

Cielo’s turn toward activism began in June, when she started an internship with the Project Summer Employment in Law Firms (SELF), a program that connected her with a group of lawyers connected to the Public Law Center (PLC), a Santa Ana nonprofit that provides free legal services to low income residents and other Orange County nonprofits.

Cielo received her training through PLC then, due to the pandemic, she started working independently, volunteering as an interpreter assisting detainees, among other activities.

One such Adelanto detainee was Pedro Chicas, a 27-year-old from Usulután, in eastern El Salvador, who’d fallen into the hands of immigration authorities in January 2020 based on a previous arrest for drunk driving.

“I don’t know what to do, I’m desperate,” Chicas confided last April 2020 to his cellmate George Napoles “Napo” Leyva, a 34-year-old Cuban immigrant who’d made friends with Cielo’s father. Chicas had lost contact with his lawyers, so Leyva put him in touch with Cielo, who offered to help him.

The young woman tracked down the lawyers, who took up the case again. She also contacted Chicas’ mother, who lives in South Los Angeles, to enlist her help, and the judge who was handling the case, to discuss the impact that Chicas’ absence was having on his family.

At least once a week, Cielo called the detention center to check on Chicas. On several occasions she sent him money for essentials — soap, toothpaste, shampoo.

“For me it was like an angel sent by God,” Chicas said. “It helped us greatly, to this day I am grateful to her.”

Cielo also encouraged Leyva to stay hopeful while trying to regain his liberty. One night in August, Cielo and her father went to a liquor store to buy a stamp and print some photographs of Leyva’s daughters, to send to him to lift his spirits.

Now, when she thinks back on those days, Cielo can’t recall how she found time to do everything.

“It was something that mattered to me. Because of what happened with my dad, I made the time, but I don’t even know how.”

Separately, as the COVID-19 pandemic grew, advocacy groups had sued U.S. Immigrations and Customs Enforcement, calling for the release of detainees to stem the spread of infection. In response, the agency began freeing detainees — Leyva last September, Chicas in November.

Cielo’s advocacy work on behalf of her father and the other men eventually formed the heart of her Harvard application essay, which took her about four months to write. At first she struggled to put words to paper, because the trauma of her father’s arrest and detention had created an emotional block. She had tried to keep that memory from her mind by focusing on her schoolwork, but the tactic no longer worked.

“I couldn’t write a sentence, because I started crying,” she recalled.

As the days passed and she labored to shape her feelings into sentences, she began sharing her thoughts with her family for the first time, which served as a kind of catharsis. In October, when she had only a week left to apply, she decided to erase everything she had written because “it felt too cold.”

“I started over,” she said.

She began with the haunting phrase, in Spanish, that she asked her father when she went to visit him shortly after he’d been detained at Adelanto. “¿No puede pedir que le bajen?” — “Can’t you ask them to turn down” the air conditioning?

It’s a common complaint at such facilities, and immigrants call them hieleras — iceboxes.

“I hiccupped through tears on one of my weekly visits to Adelanto Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Processing Center, one of the largest in the country,” her essay continued. “My father’s pink, peeling scalp exposed raw skin. He shook his head in resignation and his dejected eyes reflected knowing, ‘We ask for the air to drop but it gets colder.’”

One of the first people to hear Cielo’s dramatic story was Gloria Montiel, a professor at Claremont University who graduated from Santa Ana in 2005 and earned her B.A. at Harvard in 2009 and her M.A. two years later. Last October, Harvard sent Montiel an email asking her to interview Cielo.

“The interview and the essay begin to distinguish the students, because there you see the heart and soul of what a student represents,” Montiel said.

Montiel was immediately impressed with Cielo’s involvement in her community and with the leadership qualities and passion she demonstrated in helping her father and the other detained immigrants. Top-notch grades are not enough to be admitted to Harvard, Montiel said, because the university also “wants to prepare students who are going to be leaders in their communities or a higher level.”

“Regardless of her personal tragedy, she used all the power that she has as a 17-year-old girl to mobilize the system and help others,” Montiel continued. “Cielo is going to be an unstoppable force in our community.”

As for Cielo, although she’d applied to eight other universities, Harvard was her top choice.

“This was my hope, it was my school that I wanted,” she said.

When he heard that his daughter had been accepted at Harvard, Héctor Echegoyén was more thrilled than surprised.

“Since she started studying she has always given us gifts, in the sense that she has taken very high marks,” said the native of San Pedro Nonualco.

A video that one of Cielo’s sisters posted about her Harvard acceptance has gone viral. But although many of her peers are social media addicts, Cielo opened an Instagram account only in December, to thank the people who congratulated her on her success. She will be the second member of her family to attend university. One of her older sisters, Michelle, graduated from Georgetown in 2013.

“I haven’t seen my daughter texting on her cell phone, occupying her time in vain,” her father said, “just studying, studying, reading books, and all that has led to success.”

The knowledge that her daughter will be studying biology, and hopes to become an oncologist someday, is a balm for Soriano, who wanted to train as a nurse in her native Oaxaca, in southern Mexico, but had to quit school after fifth grade. “Now I see my daughter’s dream and mine is realized in her,” she said.

In the Santa Ana district, Superintendent Jerry Almendárez said he believes Cielo’s achievement will inspire other students to aim for college. The 46,000-student district is 92.5% Latino, and 45% of students are English learners. Santa Ana Unified was founded in 1888; to date, nine students from the district have gone to Harvard. Cielo will be the 10th.

“This is truly an amazing achievement not only for Cielo, but for all the students she represents, for her teachers who have supported her on her journey, and for the Santa Ana community,” Almendárez said.

Jeff Bishop, principal of Santa Ana High — 98.9% of whose students are Latino and Latina — said Cielo’s achievement will reverberate through the community. “Cielo is positioned to be that leader who inspires both generations before her, and generations to come,” Bishop wrote in his letter of recommendation to Harvard.

Cielo still is unpacking memories of Dec. 17, when she and her family sat in front of a computer awaiting word about her application. In the video of that moment, recorded by one of her sisters, shouts ring out and confetti blasts through the family living room when she receives the nod from New England.

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.