UCLA doubles down on ethnic studies expansion amid fraught national politics

- Share via

More than five decades ago, Morgan Chu was taught a version of American history that all but ignored the experiences of Asian Americans like him.

Chu, an attorney who grew up in New York and moved to Los Angeles to attend UCLA, never learned that the U.S. government barred Chinese people from immigrating to the United States in the 19th century and incarcerated tens of thousands of American citizens of Japanese ancestry without charges during World War II.

He was not taught about state laws in the early 1900s that prevented Asians from owning land or, even earlier, marrying outside their race. Nor did any of his classes recognize the contributions Asian Americans have made in shaping the nation beyond a scant mention of Chinese laborers who helped build the transcontinental railroad.

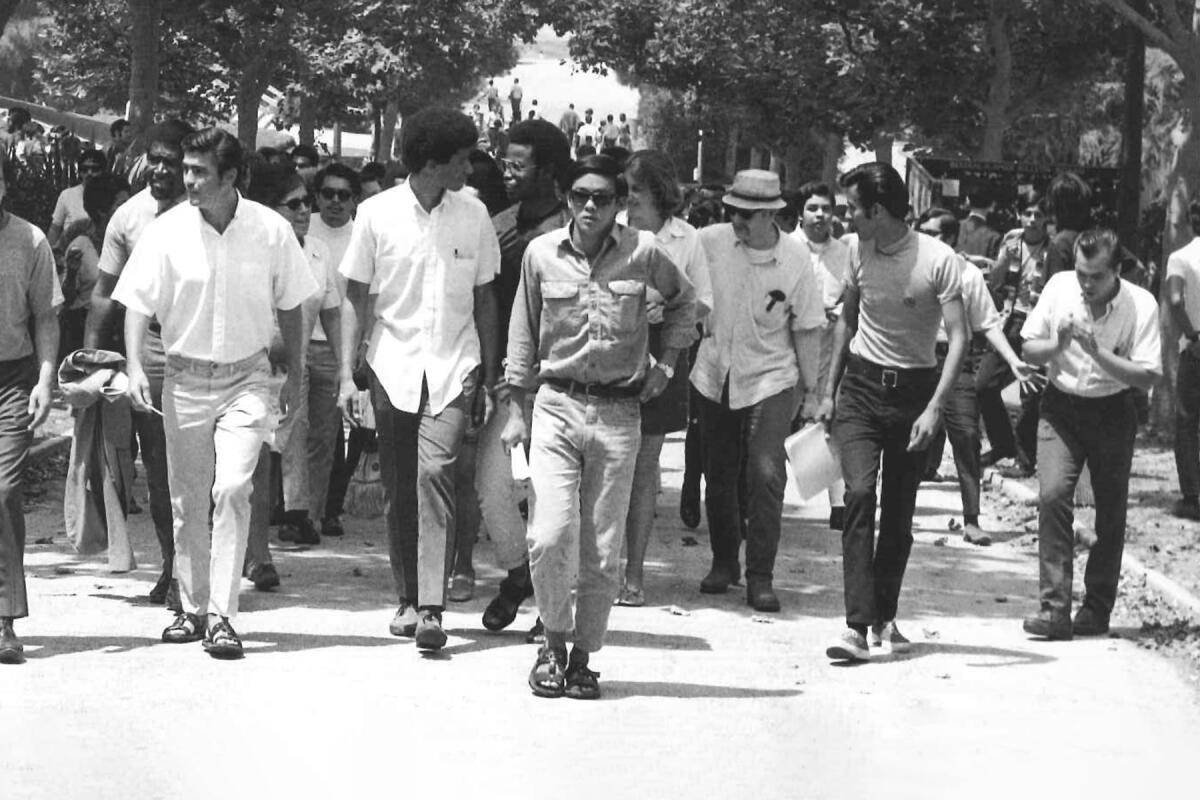

But in 1969, Chu and his wife, Helen, then a fellow Bruin, helped push UCLA to create some of the first ethnic studies programs in the nation, after joining scores of other students in protests, rallies and meetings.

Now, 55 years later, the Chus are doubling down on their commitment with a $10-million gift to create endowed chairs for Asian American, African American, Chicano and American Indian studies centers housed in the UCLA Institute of American Cultures. The gift, announced Monday, will also fund research projects and programming across the institute — cementing UCLA’s role as a national leader in this academic field.

The support for ethnic studies comes at a fraught political moment as attacks escalate against the field — including efforts by some California school districts and conservative states such as Texas and Florida to control how race and racism are taught in schools. Attacks have focused on “critical race theory” — a university-level academic framework that seeks to examine how racial inequality and racism are historically embedded in U.S. legal systems, policies and institutions. The theory, and ethnic studies, have been cast by some as an effort to portray white people as racist oppressors.

California is the first state in the nation to require an ethnic studies class for high school graduation under legislation signed into law in 2021. The California Community Colleges and California State University systems also require students to take an ethnic studies course for an associate and bachelor’s degree, respectively.

The University of California has been enmeshed in a protracted review process since 2020 over whether to require ethnic studies for admission and what the course content should include. UC requires all undergraduates to complete a course in “American Histories and Institutions,” which can be ethnic studies, economy, history, political science or related disciplines.

The University of California enrolled a record number of California undergraduates in fall 2023 and cut out-of-state students to accommodate surging local demand for seats.

Some critics have urged UC to reject any ethnic studies admission requirement in part because they fear how Israel would be discussed in such courses — particularly if critiques of colonialism and imperialism against marginalized communities include the plight of Palestinians.

The Chus stress that their gift — the largest ever received by the institute — was not prompted by the politics of the moment. Morgan Chu said the couple want to support and sustain a field of studies he likens to a “rainbow with contrasting colors and different points of view” that can help deepen understanding and bridge divides among people.

“It’s just a way to teach everyone about the richness of the history and background of all cultures,” said Chu, who became a prominent litigation attorney after earning three degrees, including a doctorate at UCLA, a master’s degree at Yale and a law degree at Harvard. Helen Chu enjoyed a long career as a public school teacher after her UCLA graduation.

UCLA Chancellor Gene Block said the gift will help the campus advance its scholarship and teaching in the field.

“UCLA has long been at the forefront of the examination of the histories, cultures, contributions and experiences of different racial and ethnic groups in the United States,” he said in a statement. “The Chus’ investment will allow us to deepen the impact of this essential work.”

Shannon Speed, the director of UCLA’s American Indian Studies Center, called the Chu gift a “game changer” that would ensure the survival of ethnic studies at a time of fiscal challenges in higher education and political attacks against the field.

The gift is particularly powerful because it supports all four ethnic studies centers at the institute, said Celia Lacayo, assistant director of the Chicano Studies Research Center.

The funds will endow directors’ chairs for the African American, Chicano and American Indian studies centers. The Chus also plan to fund an academic chair for a faculty member in the Asian American Studies Center. Their prior gifts have funded chairs for a director of that center and a professor in Asian American studies, along with a scholarship fund.

Those four groups have formed the core of ethnic studies since the academic field’s inception in the late 1960s when the Black Student Union and a coalition of student groups at San Francisco State University, known as the Third World Liberation Front, began a five-month strike demanding inclusive curriculum, equal educational access and more faculty of color.

Lacayo noted that the 1960s struggles for civil rights and ethnic studies drew people from all backgrounds who believed in social justice and racial equity, and the donation to all four centers reflects that legacy. “All four of these groups fight [for] racial equity, but we also fight together,” she said. “That coming together is very critical.”

Chu recalled the power of unity during his own student activism. “We locked arms in 1969 to move forward and it was a wonderful, beautiful thing. And when we now have been able to help support all of the centers, we wanted to do that because of the common issues we shared 50 years ago, and will probably share into the future.”

The UCLA institute and its centers were launched just months after San Francisco State established the nation’s first College of Ethnic Studies following the 1968-69 strike.

The Chus joined scores of other students making similar demands at UCLA. But Morgan Chu’s serendipitous encounter with a key UCLA official at a poker game would greatly help the cause. The official was David Saxon, then UCLA’s second-in-command as executive vice chancellor of academic affairs who would go on to become UC president in 1975.

In another move, UC regents delayed action until March on a controversial proposal to ban faculty from expressing opinions, such as criticism of Israel, on university websites.

Chu said Saxon was initially resistant to the demand for separate ethnic studies programs, questioning why the material could not be woven into existing history, sociology and other courses. But he eventually got on board and, Chu said, helped sell the idea to other campus leaders.

Today, the centers’ affiliated faculty have grown from a handful in 1969 to about 250 throughout the campus engaged in law, education, public health, the arts and other disciplines. The institute and centers have awarded about $7 million in research and fellowship grants, produced more than 3,000 publications and boast some of the nation’s best ethnic studies libraries and archives, including Chicano film and music and the Japanese American Research Project collection with rare oral histories of early immigrants, said David Yoo, the institute’s vice provost.

The centers are also active in civic work through wide-ranging community partnerships with social service agencies, museums, historical societies and others.

They collectively work on some issues — including a project on mass incarceration and proposed curriculum for ethnic studies courses that legally must begin in the 2025-26 school year.

The centers also undertake their own community-focused work. The Asian American Studies Center, for instance, publishes two major academic journals, has produced some 50 books and reports and led research into such topics as the hidden face of Asian American homelessness and anti-Asian hate crimes.

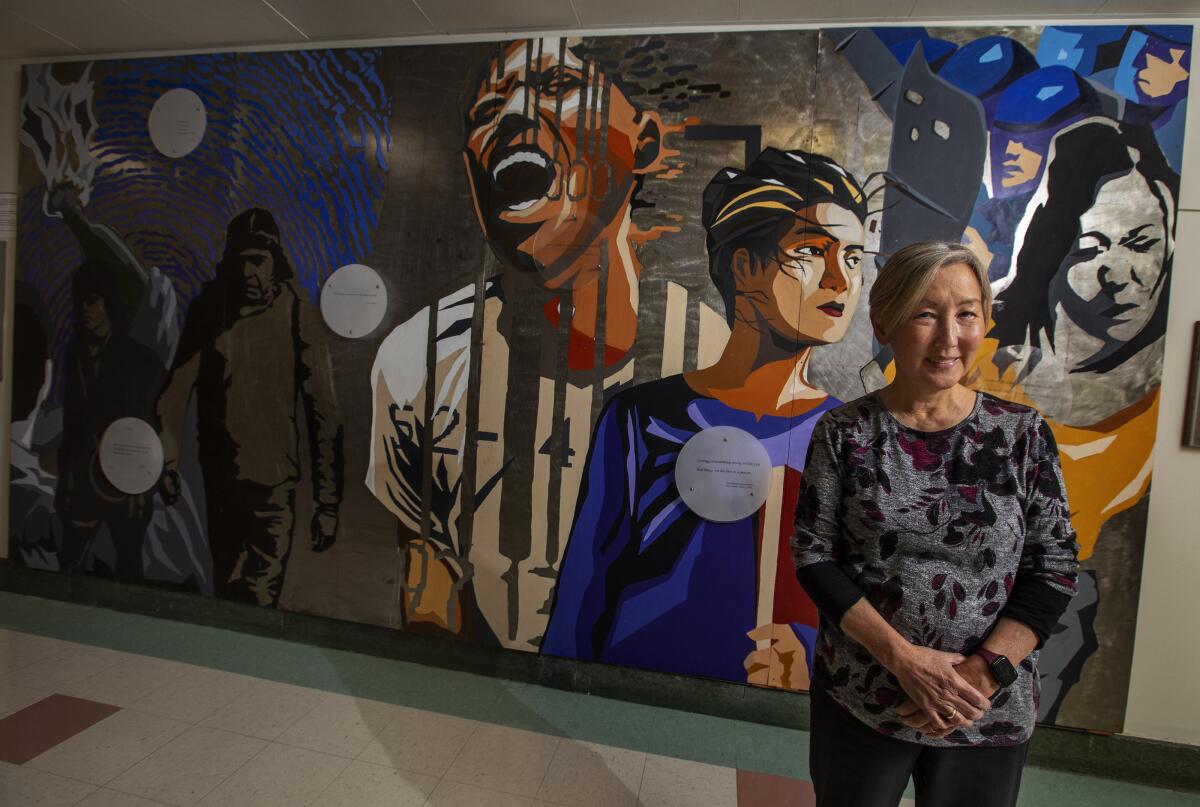

“Many of our histories have been erased or marginalized or maligned, leading to stereotypes that allow so much hatred and propaganda to take flight,” said Karen Umemoto, director of the Asian American Studies Center. “The whole origin of ethnic studies has been a project to allow our voices to be heard ... so we can do thoughtful research and tell the stories of our experiences and histories for the world to know.”

The Chicano center’s projects include a student-led summer voter education and research initiative and a state-funded effort to research and promote equity for Latinas in careers, civic leadership and health.

The Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies supports research into mass incarceration, reparations for descendants of enslaved people and also funds a fellows program for students to work with faculty in studying conditions of Black life.

The American Indian Studies Center is leading several research projects, including Indigenous perspectives on water issues, such as the diversion of snowmelt and groundwater from Northern Paiute tribal homelands — known as the Owens Valley — to Los Angeles. The center is also helping build a pipeline to college for Native American high school students with outreach and assistance. UCLA plans to double the number of Native American and Pacific Islander faculty over the next several years.

For their part, the Chus said the impulse behind their long support of ethnic studies is “pretty simple.”

“We thought that teaching more about everyone in a very inclusive fashion would improve the overall educational experience for everyone,” Morgan Chu said. “Whether it’s today, or 50 years ago, or 50 years in the future, we will have a better world, a better society, if people understand one another.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.