LAUSD unequal reopening: Nearly full classrooms on Westside, emptier elsewhere

The first week of in-person school at Warner Avenue Elementary in Westwood rolled out like a joyous sigh of relief. Families lined up around the block, exchanging hugs as children chased one another on the grass.

Parent Dina Cohan was “ecstatic,” she said, before flying into an embrace with Principal Agnes Kamau just outside the entrance gate and shouting, “This is the best day in a year!”

About 95% of students at Warner Avenue Elementary were back on campus, Kamau said.

That makes it something of a rarity among L.A. public schools. There are only four communities where more than 40% of students were expected to return to in-person school, according to district data collected in a parent survey: western Los Angeles, Woodland Hills, Westchester and Venice. Each is a higher-income community, with majority-white populations in which COVID-19 has not had the same magnitude of impact as neighborhoods with larger Latino and Black populations.

In Latino-majority communities such as South Gate, East Los Angeles, Pico Union and Bell, only about 25% of students were expected to return. The disparate rates mean that, at least for now, in-person schooling will be very different from neighborhood to neighborhood, especially at the elementary school level.

At Madison Elementary School in South Gate, 10-year-old Anthony Sosa stood in line with his mother, Laura Martinez, on Thursday morning, eagerly awaiting his chance to get back to school. He wore a black Adidas face covering and had a large bottle of hand sanitizer, extra masks and hand wipes stuffed in his backpack. Only four other students would be in his classroom, he’d been told. But that didn’t dim his excitement.

“I’m going to get to play with my friends!” he said.

Once the school day started, teachers took turns taking their classes out for recess on the blacktop. One class with three students played hopscotch six feet apart. Another had five. About 42% of students at the school were expected to return, Principal Gretchen Young said.

“In this community there are a lot of multigenerational families, and there’s still concern about COVID,” Young said. “Our community has been hard hit because there are a lot of essential workers.

“As they start to feel it’s safe,” she added, “I suspect we’ll get more kids back.”

The COVID-19 death rate in South Gate is 292 people per 100,000 residents, according to data tracked by The Times. In South Gate overall, about 38% of elementary school students, 31% of middle school and 19% of high school students were expected back on campus, according to the survey, which asked parents whether they wanted to send their children back to school or keep them in distance learning.

Across the district, elementary schools show the highest percentage of students likely to return. In parts of the Westside, about 82% of elementary students are returning. In East Los Angeles, it is 36%. About 77% of parents and caregivers have returned surveys. The district has said that families who do not return the surveys will continue with distance learning.

Madison and Warner Avenue were among the 61 elementary and 11 early-education L.A. Unified campuses that opened Tuesday for the first time in more than a year. All 1,400 schools in the nation’s second-largest school district will be open by the end of April.

Although there are several factors at play in parents’ decision to return to school, communities with higher coronavirus case rates are opting in larger numbers to keep their children home, according to the district survey and neighborhood-level COVID-19 data compiled by The Times.

At Compton Avenue Elementary in Watts, where the hallways are lined with college flags, about 48% of parents had indicated they would send their children back to campus. But by Thursday, only 51 students, about 18%, were back, Principal Lashon Sanford said.

“We’re hoping as we continue to communicate, we can build that confidence,” she said.

Much of the reluctance has to do with concerns about the virus, Sanford said. In Watts, about 409 people per 100,000 residents died of COVID-19, according to The Times’ data.

But, Sanford added, “there are layers to the hard hits in communities like ours.” Families have also faced joblessness and homelessness, along with other challenges during the pandemic, she said.

Some also might need to get student coronavirus tests, Sanford said.

Under district rules for a safe reopening, students must be tested during the week prior to their scheduled return to campus and then take weekly tests after that. To get the test in advance, families were advised to go to one of 43 sites across the school system But testing was not available at most campuses, and some families said they were not able to get their child tested in time.

Many families have also said the school schedule is a challenge. At most campuses, the district is offering classroom instruction from about 8 to 11 a.m. and after-school care until 4 p.m. The extended supervision is free, which parents appreciate, but pre-pandemic supervision had lasted till 6 p.m. at many schools, making the current schedule a tighter fit for working parents.

Even with the shorter hours, about 75% of returning parents are taking advantage of the day care, according to L.A. schools Supt. Austin Beutner. At Warner Avenue Elementary, the figure is about 80%, significantly higher than before the pandemic.

On Thursday, Beutner visited Compton Avenue Elementary, stopping by a third-grade classroom with six students. He asked the few to make a video with him, encouraging their classmates to return.

At the suggestion of Principal Sanford, the students, superintendent and other school officials stood together, wiggling and shaking their arms and shouting: “All-day school is fun and cool!” for the video, which was later posted to Twitter.

The lower return rate at schools in low-income areas with high coronavirus rates “is a very real concern,” Beutner said.

“We can see the outliers, parts of West Los Angeles, which are less diverse, parts of Los Angeles which are less hard hit by COVID, more families are comfortable having their child return,” he said. “The families that have seen a loved one become sick or, God forbid, worse, or they’re seeing someone in their family lose work, that trauma does not heal overnight just because a series of elected officials get up today and say, it’s all good.... It takes time.”

Ana Ponce, the executive director of the local advocacy group Great Public Schools Now, said she would like to see the district invest in better outreach to Black and Latino communities so that families can feel confident to return. The group’s report, issued last month, concluded that students at all levels had suffered academically since the district closed its campuses, with young students and those who were already behind suffering the greatest harm.

“Sending text messages and lengthy emails and robocalls is probably not the best strategy to engage families that are disengaged or families that have already made a decision to not send their kids back,” she said. “We need a more proactive communications strategy that really gets to where the parents are so they can be moved to have more trust in the district.”

At Warner Avenue, the elementary school in Westwood where nearly all students are returning, many parents were at the forefront of the movement to push schools to reopen.

On Wednesday morning, second-grader Lenna Shahhosseini waited with her father and nanny to enter Warner Avenue. She carried a white orchid gift and a note that said, “Best teacher ever.” Lenna bluntly expressed her discontent with distance learning.

“It’s boring,” she said. “Because you can’t do anything. You have to look at the screen for three hours.”

“We are waiting for this day,” said her father, Nouri Shahhosseini, who also has a fifth-grader.

The neighborhood has one of the lowest COVID-19 death rates in the city: 41 per 100,000 residents. Westside residential communities like this have among the highest vaccination rates in Southern California.

The small number of students who are staying online are being taught by a substitute instructor with assignments overseen by the same teacher they’ve had all year.

Second-grade teacher Conny Chan said she was coordinating closely with the substitute. The curriculum, the lessons — “it’s still all me,” Chan said. “We want consistency for the kids.”

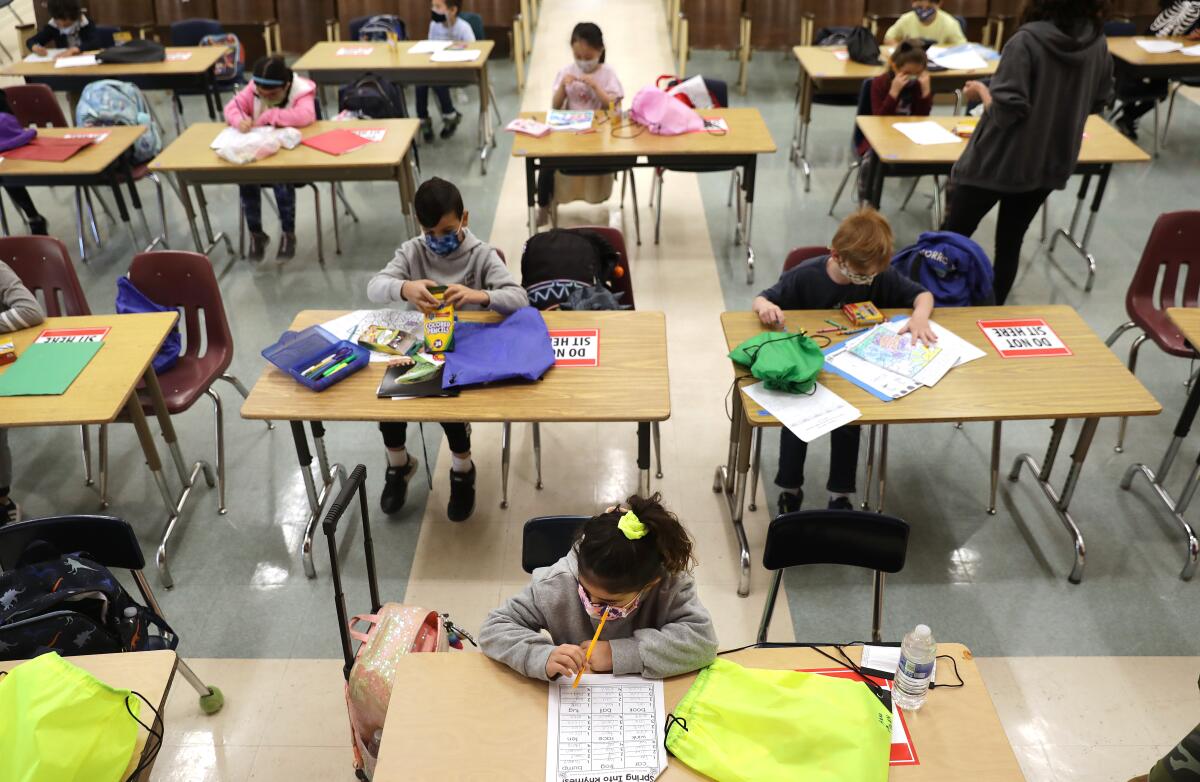

At Warner Avenue, every square foot of campus is put to purpose throughout the day, including the auditorium, the lunch shelter and the asphalt playground, which has tents to provide ad hoc areas for activities and student workspace.

At Compton Avenue Elementary, there were plenty of empty desks in the classrooms and just a few students on the asphalt playground. In one classroom, reading recovery teacher Rita Worley-Schell worked with 6-year-old Laila Howard as she spelled the word “looks” on a whiteboard with magnetic letters.

Worley-Schell, whose one-on-one and small groups’ work with first-graders provide extra help to develop literacy skills, said the students she has worked closely with since the start of the year had not yet returned to campus.

One had trouble getting tested, she said. The other two had parents whose work schedules led them to decide to keep them at home.

“It’s been tough to get consistent schedules,” she said.

Standing outside the quiet campus near a display of yellow-and-blue “Welcome back” balloons, Sanford, the principal, said she was confident students would start to trickle in with time.

“We’re ready for them,” she said. “The urgency is paramount. We’re talking about their futures.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.