Getty Research Institute gets photos of performance art ‘Happenings’

How do you archive a performance? Can you put human speech and action under glass and frame it? Stow art that unfolds in three dimensions within acid-free archival boxes, to be filed away in a cool, dark vault?

The conundrum of how best to preserve the history of midcentury American performance art — art created before phones had video cameras — lies at the center of the Getty Research Institute’s recently announced acquisition of Robert McElroy’s archive. In more than 700 prints and 10,000 negatives, the photographer documented the performative works of Allan Kaprow, Jim Dine, Claes Oldenburg and other artists whose “Happenings” grew from niche New York art events into a full-fledged pop culture phenomenon.

“The Happenings, which began in the late 1950s, marked this starting point of a new type of avant-garde in the U.S. that we see as still being incredibly relevant today and incredibly well suited for our archives,” said Glenn Phillips, acting head of the research institute’s architecture and contemporary art department. By making art from the everyday reality around them, artists such as Oldenburg and Kaprow “took the energy and spirit of abstract expressionism and allowed it to spill into gallery.”

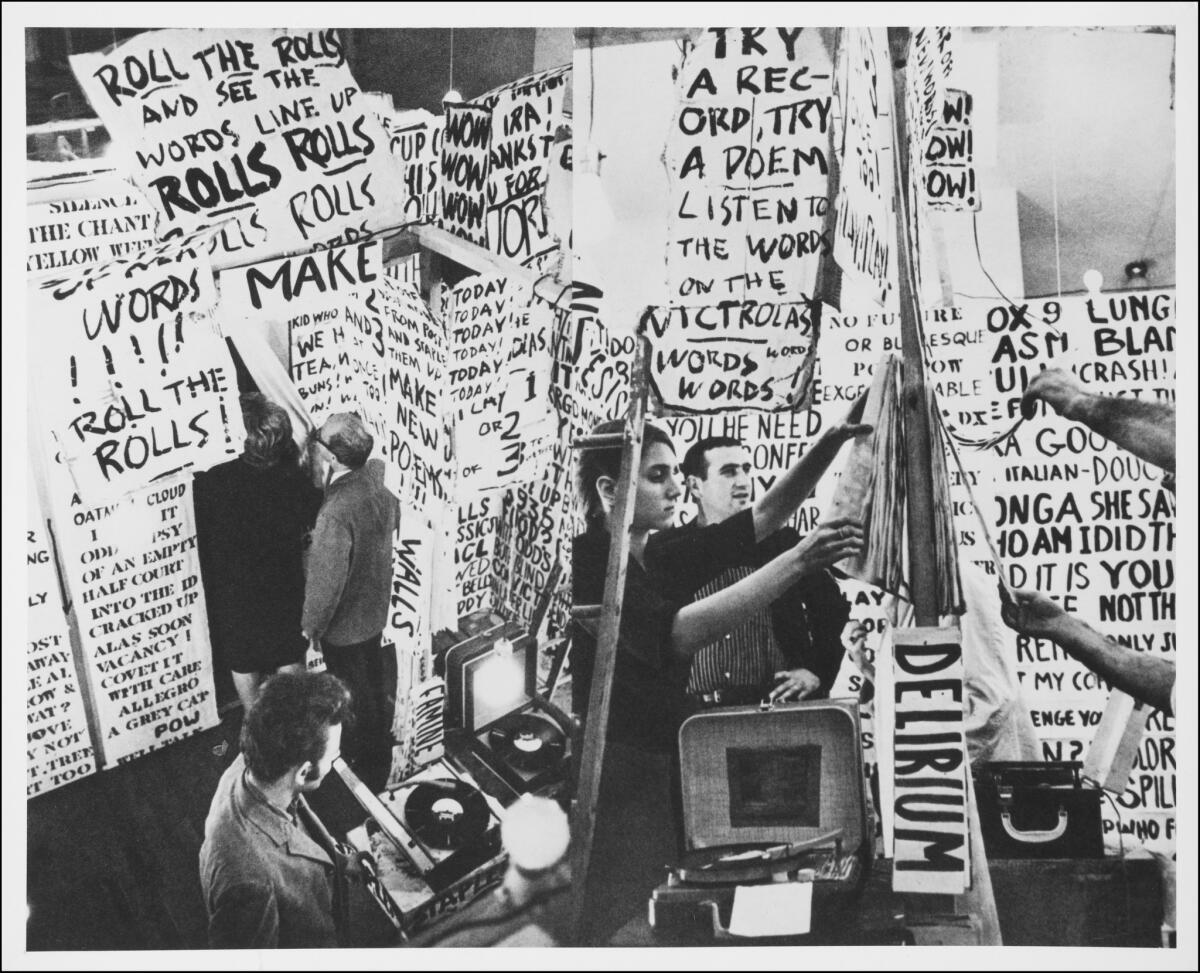

For “Words,” Kaprow set up two connected rooms, the first filled with stenciled pieces of cloth. “You could manipulate them, move them around. Visitors could roll the rolls, tear off the word strips, staple them around,” Phillips said, while Victrolas played any number of things — “records of Kaprow’s lectures, advertisements, ramblings of nonsense.”

In the intimate second room, lighted by a single bulb, more strips of cloth hung like cobwebs. People could contribute to the installation by leaving their own small notes.

McElroy’s images provide “the tiniest hint” of the experience, which is precisely why the artists loved him — and partly why the Getty wanted to acquire the work. (The research institute has not scheduled an exhibition of the archive, but a spokeswoman said it may be put on public display.) Other photographers certainly recorded the Happenings and tracked the art scene, but the artists liked McElroy because his photos echoed their intentions, Phillips said.

“The Happenings were very casual, striving in a way toward the undramatic,” he said. In that vain, McElroy’s images are not trying to capture the perfect dramatic moment in the same way that a contemporary Playbill picture might try to encapsulate the drama onstage in a single frame or a ballet photographer might strive to catch the principal dancer at the apex of her leap. “With McElroy photographs, you never have the feeling that this is the one moment,” Phillips said. “You always know it’s a fragment of what’s going on.”

The photos feel as ephemeral as the performances.

The archive of McElroy, who died in 2012 at age 84, includes a strong selection of Oldenburg’s performances and some of the earliest works of Yvonne Rainer, Phillips said. Crucially, the images show not just the performers but also the audience and its reaction.

“I’ve met so many people who said, ‘Oh, I was in a Happening,’” Phillips said. “It’s so rare that something that starts as a tiny sliver of the art world ends up as a fad.”

Twitter: cnakano

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.