From the Archives: With ‘The Indian in the Cupboard,’ Melissa Mathison hopes she’s written a script for the ages

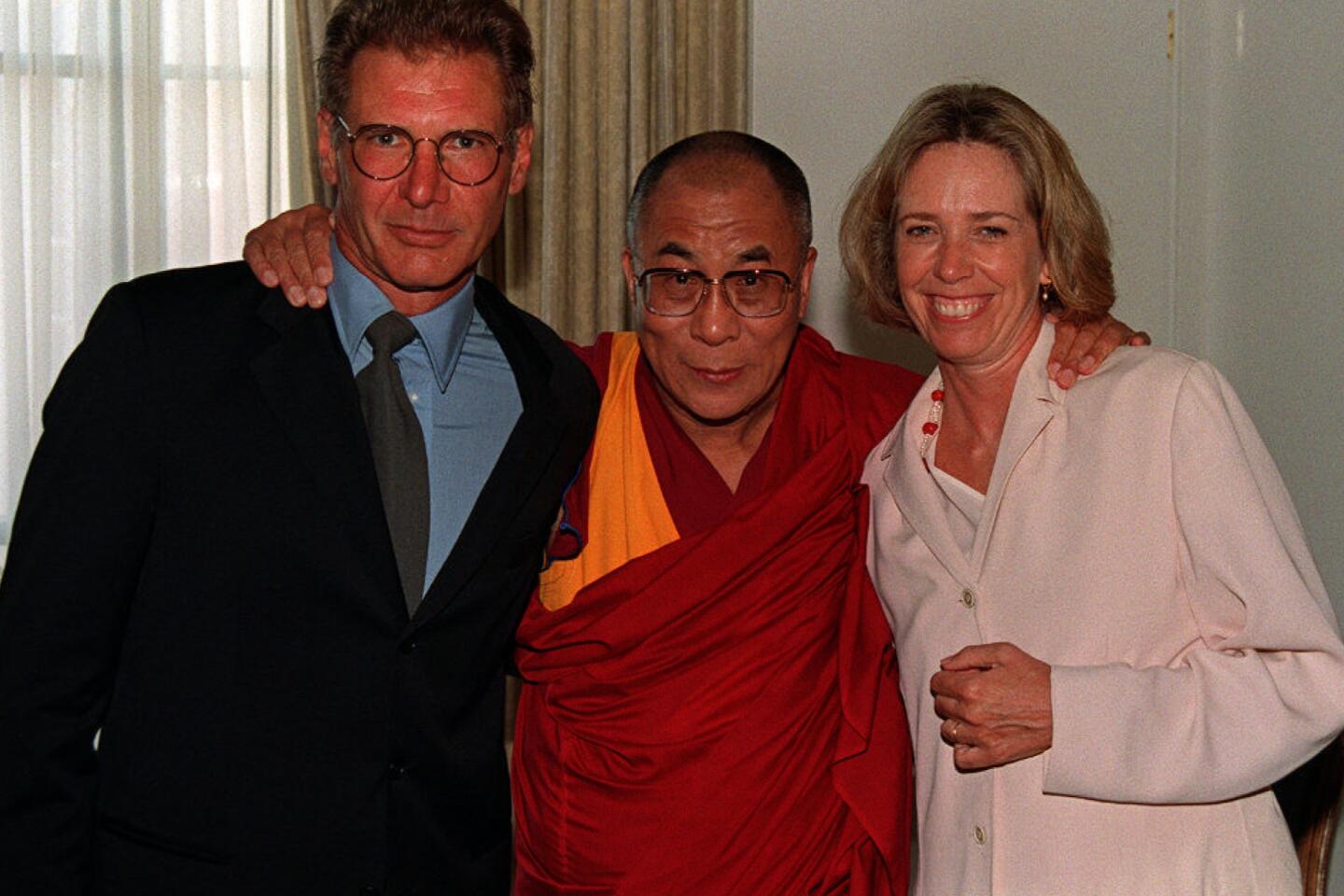

Melissa Mathison and then-husband Harrison Ford attend the premiere party for “Clear and Present Danger” on the grounds of Paramount Pictures on Aug. 3, 1994.

Melissa Mathison has been here before, waiting for a gentle fantasy movie she has written for children to open.

Thirteen years ago, the movie was “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial,” which became a phenomenon, then a classic. The magical tale coming to theaters Friday is “The Indian in the Cupboard,” based on the prizewinning novel by Lynne Reid Banks about a 9-year-old boy with a supernaturally endowed wooden cupboard, capable of bringing miniature plastic toy figures to life. Mathison says that this time, she and “E.T.” producer Kathleen Kennedy, collaborating again, “were trying to make a classic movie.”

What elevates a film to classic status is a favorite topic of dinner conversation in Mathison’s home.

“I don’t know where he got this idea,” she says, “but my 8-year-old son wants to know if every movie he sees is a classic. He says, ‘What about “Coneheads,” Mom? Is that a classic?’”

Not by Mathison’s definition. She awards that designation to “a movie that is more than something that is watched perennially. It must create a really strong feeling--whether it’s horror, adventure or mystery. You can go back to the film again and again and you know you’ll get that exact same feeling.”

To infuse screen stories with emotion has long been among Mathison’s missions; before “E.T.,” she wrote “The Black Stallion” and “The Escape Artist,” both sensitive children’s stories. But accompanying her son, Malcolm, and 4-year-old daughter, Georgia, to recent movies that unabashedly celebrate all that is dumb and dumber strengthened her resolve to craft quality entertainment for children.

“I go to movies with my children and see fat kids burping, parents portrayed as total morons and kids being mean and materialistic, and I feel this is really slim pickin’s here,” Mathison says. “There’s a little dribble of a moral tacked on, but the story is not about that. We’d get back in the car after seeing a movie and I’d say, ‘Now, what did you think about this?’ and they had nothing to say.

“There was nothing to talk about, because the movie had just been pratfalls and stupid jokes. It needed no imagination to be appreciated.”

It certainly isn’t the genre that offends Mathison--she has collected children’s literature for years and reads with her kids for 45 minutes every night. That practice has reinforced her belief that children can digest meaty material.

If children are given some real content, they can feel powerful with their own understanding of it.

— Melissa Mathison

“If children are given some real content, they can feel powerful with their own understanding of it,” she says. “I think a movie like ‘Indian in the Cupboard’ will instruct them how to proceed as people. They can think about whether they would have done something the way a character did, how they would have felt about an event in the story.

“There’s stuff in it that they can think only they discovered. The material massages that imagination muscle in order to help it get bigger and stronger. Children are primed to take in something of more moral value than they’re getting. I know I’m blowing my own horn here, but ‘E.T.’ had value to it, in terms of the feeling about yourself that you walked away with.”

When Mathison talks about moral value, the expedient stench so often present when a politician utters the same words is not in the air. She projects a tempered warmth uncorrupted by insincerity. Kennedy describes her as “very secure and comfortable in her own skin.”

Tall, lean and sporty, at 45 Mathison has a fresh-faced attractiveness that she laughingly points out is not best showcased in the glare of a paparazzo ‘s flash. (Appearing on the arm of husband Harrison Ford makes her the occasional target of photographers’ ambushes.)

When Mathison was a girl, her real-life adventures took place in the wild Hollywood Hills, where a favorite pastime was hunting for coyote tracks. As one of five children born to a journalist father and a mother who sometimes worked in publicity, Mathison remembers the household in which she grew up as a place where independence and creativity were encouraged.

“We weren’t your mainstream ‘50s family,” she says. “Both my parents had wonderful, eccentric, artistic friends who treated us as friends as well. How your mind worked was considered important.”

Mathison was a political science major at UC Berkeley when she took a leave to work as Francis Ford Coppola’s assistant on “The Godfather, Part II.” She wasn’t thinking about a career in movies then, but for a 22-year-old, the atmosphere of a film set was electric.

“All the things that were tedious and mundane to most people were exhilarating to me,” she says. “I had been working in a bakery. Bringing coffee to Al Pacino was exciting.”

Coppola prodded her to write, and a few years later he set her to work on “The Black Stallion.”

For weeks, she wrote script pages after midnight that were filmed the next day.

“Francis said, ‘You can do this,’ and that was it,” Mathison remembers. “Somebody else might have said, ‘How much am I being paid, and I need 12 weeks.’ I just said, ‘OK. And I get per diem on location?’ We all agreed the movie should be like a children’s book, with just pictures. That’s when I learned to take out the words, to tell the story visually, which is the best training there is.”

By the time Mathison had become Ford’s companion, traveling to far-flung locations with the company making “Raiders of the Lost Ark,” she had worked as a stringer for Time in San Francisco, assisted Coppola on “Apocalypse Now” and written “The Escape Artist.” Steven Spielberg turned his attention away from directing Indiana Jones long enough to ask Mathison if she would like to write a children’s movie about a visitor from outer space.

It might be tempting to write Mathison off as a woman blessed with good luck and an instinct for being in the right place at the right time. Coppola was a family friend; she had baby-sat for his children when they lived in Los Angeles. Her introduction to Time came via a friend of her father’s, the bureau chief. But a facile analysis of Mathison’s success based on the right connections would be inaccurate, if not insulting.

Spielberg might have said to a lot of writers, “Let’s do a story about a benign alien, accidentally left behind by his spaceship, and his friendship with a boy.” How many of them could have come up with a script informed with the humor, suspense and sense of wonder of “E.T.”? Mathison wrote the first draft in eight weeks.

As Kennedy recalls, “Steven came in and said, ‘I’ve read Melissa’s draft. Let’s shoot it.’”

“E.T.” was a hard act to follow, a fact that didn’t escape its author.

“The whole thing just jelled in a moment in history in a way that was really thrilling,” she says. “I knew that I had gotten the gold ring. I was a little paralyzed by the thought, ‘Now what should I do?’ I hadn’t spent 10 years suffering and striving to achieve success, so there was no revenge in my heart. I didn’t have to prove that I could do it again. I just worked on projects I wanted to do by myself. I tried to become a better writer. I developed a greater respect for what I had had the luck and ability to do successfully.

“I read a good definition of luck--that it is being prepared when the situation arises. It’s true that in the beginning I was given opportunities, but I was able to deliver. I’ve come up with the goods.”

For years, producers and agents sent every children’s story and fantasy script Mathison’s way. She has always been interested in juvenile literature and deems writing for children a great honor. But she doesn’t label herself exclusively a children’s writer, and says she turns nearly everything down.

She is more likely to write a script based on material she has found than to accept a writing assignment. (She took “The Indian in the Cupboard” to Kennedy, suggesting that it would make a great movie.) After “E.T.,” her choice of subjects was eclectic, ranging from “Son of the Morning Star,” a historical miniseries based on Evan S. Connell’s book, to a script based on a boy detective, the protagonist of a series of popular European comics.

Some of her scripts were produced, others weren’t. Whether she was enthusiastically consulting Custer experts for the miniseries or enduring the frustration of seeing a much-loved screenplay written for Bill Murray not go into production, writing has always been only part of Mathison’s life.

“What she does doesn’t define who she is,” Kennedy says. “Writing is a talent she loves having an opportunity to exercise once in a while. It isn’t something she could just leave, but it isn’t all-consuming. Both she and Harrison have many, many interests that go beyond the movie industry. They talk about a wide variety of things, and that comes through in the kind of work that she does. She’s a voracious reader and interested in other people, interested in what’s going on around her. I think that’s why her work is so sensitive to what’s going on.”

The first draft of “E.T.” was not a fluke. Mathison is known for turning out fast, nearly perfect screenplays, and both Paramount and director Frank Oz committed to “The Indian in the Cupboard” after reading her earliest version of the script.

“Which doesn’t mean you don’t rewrite,” she says. “There are changes dictated by budgetary restrictions. A script is a jigsaw puzzle. You pull a piece out and another whole piece doesn’t work anymore. So you’re starting from scratch over and over again. But that’s screenwriting. All you do is rewrite, your whole life. They’d have you rewrite after the movie came out, if they could.”

The particular gift she brings to her work, Mathison believes, is an ability to unearth the heart of a story. Her somewhat subversive personal method of surviving the potentially destructive aspects of collaboration in Hollywood involves ignoring the negative.

“I avoid listening to too many people’s comments about my script,” she says. “I have learned to take in what is of use. It’s too frustrating looking at somebody’s notes who didn’t get what you were doing. If somebody says, ‘This stinks, and here are all the reasons,’ that’s not going to help you. You should listen to the people who like what you’re trying to do.”

In “The Indian in the Cupboard,” Mathison’s focus was on bringing levels of meaning to the story.

“It is obviously about responsibility and compassion and wisdom, and I think it will be clear to children that you have to take care of someone and their feelings--you have to respect human life,” she says. “But to me there was a subtext that was about things changing. I think the idea that nothing stays the same is one of the hardest for a child to absorb. The lesson it leads you to is to be of value to your time. To be here and now and aid what you can. The challenge was to make the movie less of an adventure and more of a profound experience, to put more emotion into what happened.

“My idea of a good fantasy is something that’s absolutely grounded in reality. And there’s a little element that doesn’t belong there--and that’s the fantasy element--that you have to react to and deal with in a completely real way.”

A fantasy blended with reality might be a description of Mathison’s life. Her early, stunning success and enduring relationship with a handsome, respected and well-liked movie star might be the stuff of many women’s fantasies. Yet the couple have deliberately sought to stay down to earth by conducting their family life as normally as possible, even moving away from Los Angeles to be in a rural Western area where the spectacular natural beauty overshadows any man-made entertainment or the people who make it.

There is the grit of the real world in Mathison’s work, in the time she devotes to developing and exercising her muse and in the professionalism that carries her through its most nerve-racking and tedious stages. She is not one to complain. “I have a very happy, blessed life,” she says.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.