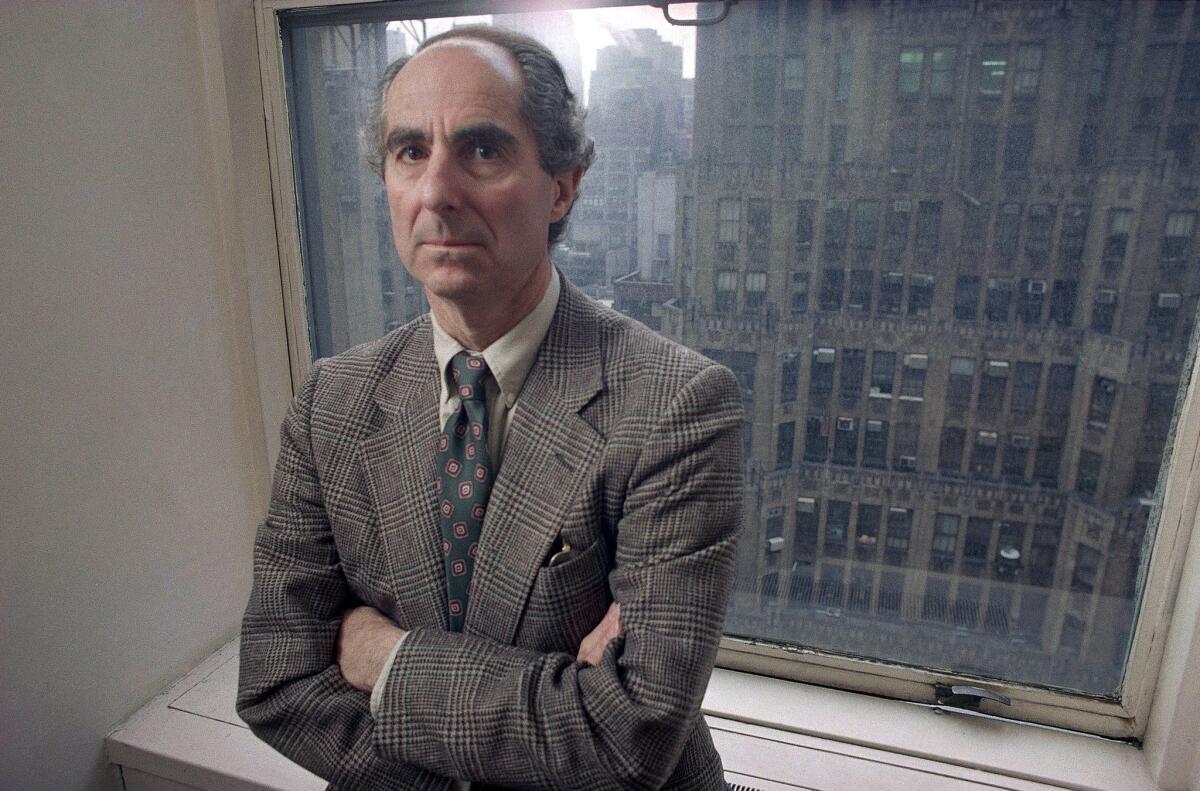

Philip Roth gets ‘Unmasked’ on PBS -- or does he?

I’m of two minds about “Philip Roth: Unmasked,” the “American Masters” documentary that airs Friday night on PBS.

On the one hand, it’s always a pleasure to hear Roth, who turned 80 this month and recently announced his retirement, speak — about the push and pull of family, the consolations (or lack thereof) of sex and literature and the never-to-be-resolved issue of identity, all subjects that have infused his writing for more than 50 years. On the other, the film, which marks the first time Roth has given an extended interview on camera, is oddly toothless, a by-the numbers hagiography.

Partly, this may have to do with Roth, who has long been interested in managing his legacy. But still, it makes me wonder: Why did writers-directors William Karel and Livia Manera check their inquisitive spirit at the door?

Don’t get me wrong: I revere Roth’s work, which is as essential as any in American literature, an evocation of place and self and society that is ambitious, messy, unfettered, ribald. We take him for granted because (it seems) he has always been there, from the late 1950s, when he won a National Book Award at age 26 for his first book “Goodbye, Columbus,” through the tumult of the 1960s and 1970s and on into a second flowering in the 1990s and 2000s, with their unrelenting culture wars.

And yet, it is precisely this taking him for granted that is the problem, for there’s more to Roth than meets the eye. Because much of his work (especially the nine novels that revolve around the writer Nathan Zuckerman) appears to be baldly autobiographical, we have the sense that we know him when in fact, as he suggests at the end of his astonishing “The Counterlife” (1986), “Being Zuckerman is one long performance and the very opposite of what is thought of as being oneself.”

Therein, I suppose, lies the problem, for a documentary is nothing if not a representation of the self. When it comes to Roth, however, that’s too reductive, for this is a writer who contains multitudes.

“I’m not crazy about seeing myself described as an American Jewish writer,” he declares at the start of “Philip Roth: Unmasked,” as if laying down a gauntlet. “I don’t write in Jewish. I write in American. Most of my work, nine-tenths of it, takes place in America. I was raised in America. I am an American. Therefore, I am an American writer.”

And yet, no sooner has he said this than he brings up his story “Defender of the Faith,” about “some Jewish guys in the Army,” published in the New Yorker in 1958.

“I met with opposition right off,” Roth recalls. “… The New Yorker began to get letters, dozens and dozens of letters, canceling subscriptions, by Jews, and I began to get angry phone calls from various Jewish organizations. Would you write these stories if you were in Nazi Germany? And I was suddenly being assailed as an anti-Semite. This thing that I detested all my life. And a self-hating Jew. I didn’t even know what it meant. It never dawned on me when I was writing that story that this was going to cause a conflagration. But that’s what happened when I began to write.”

That’s a fascinating moment, for its glimpse of a young Roth, still in the process of becoming, and for what it says about the tensions that have defined his career.

The question about Nazi Germany recurs in his 1979 novel “The Ghost Writer,” the first to feature Zuckerman, as a young writer in the 1950s trying to navigate similar territory — although this connection is not developed in the film.

Instead, Roth walks us through his writing life, recycling tropes (most notably that “Portnoy’s Complaint” represented an attempt to get on the page the outrageous humor he shared with his friends) that largely keep to the surface of his work.

Of the quartet “Zuckerman Bound” — which gathers the first four Zuckerman books, “The Ghost Writer,” “Zuckerman Unbound,” “The Anatomy Lesson,” “The Prague Orgy” — Roth says, “When all of those books were taken together, you have my story.” Of the 1995 novel “Sabbath’s Theater,” considered his most scabrous and sexually provocative, he explains, “Shame isn’t for writers. You have to be shameless. You can’t worry about being decorous. I couldn’t have written ‘Sabbath’s Theater’ if I felt shame.”

That’s all true, in a basic sense, but it overlooks what makes Roth important, which is everything that bubbles up from underneath. Again, “Portnoy’s Complaint,” with its structure borrowed from a psychoanalytic session, is enlightening, the entire novel one long rant until, finally, the therapist offers what Roth specifically labels a “PUNCH LINE”: “So… Now vee may perhaps to begin.”

That freedom, the permission to say anything, opened Roth’s writing, changing the way he thought about what fiction could do. It’s no understatement to suggest that his subsequent masterworks — not just “The Counterlife” and “Sabbath’s Theater,” but also “Operation Shylock,” “American Pastoral,” “The Human Stain” — have their roots here.

“I was very curious as a writer as to how far I could go,” he observes in the documentary. “What happens if you go further?” And: “I’ve had to fight my way to the freedom of drawing upon what I know. Life isn’t good enough in some ways. If it was just a matter of putting things down that happened to you, or happened to your wife, or happened to your friend … you wouldn’t be a novelist.”

This is the Roth whose work so moves me, the transformative Roth, the one who aspires to Kafka’s dictate: “We should read only those books that bite and sting us.” Such a Roth, though, emerges here only in pieces, in between the talking points.

Part of the problem is the paucity of outside voices; we get a few scattered comments from Jonathan Franzen, Nicole Krauss, the New Yorker’s Claudia Roth Pierpont and Mia Farrow (Mia Farrow?), but for the most part, these are glosses on the main event.

Even more, it’s the inability of Karel and Manera to get Roth to reveal himself in any unexpected way. Sure, he is discursive, thoughtful, and (yes) very funny, but where is the wildness that has defined his work?

“When a writer is born into a family, the family is finished,” Roth tells us, quoting Czeslaw Milosz, but such a danger is rarely found in “Philip Roth: Unmasked.”

ALSO:

A conversation with Philip Roth

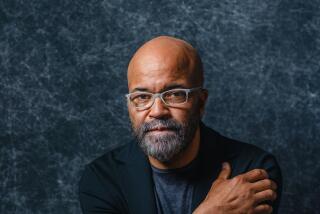

Remembering Chinua Achebe, a writer who connected us to the world

david.ulin@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.