Iranian bookstore gives exiles a taste of freedoms lost in homeland

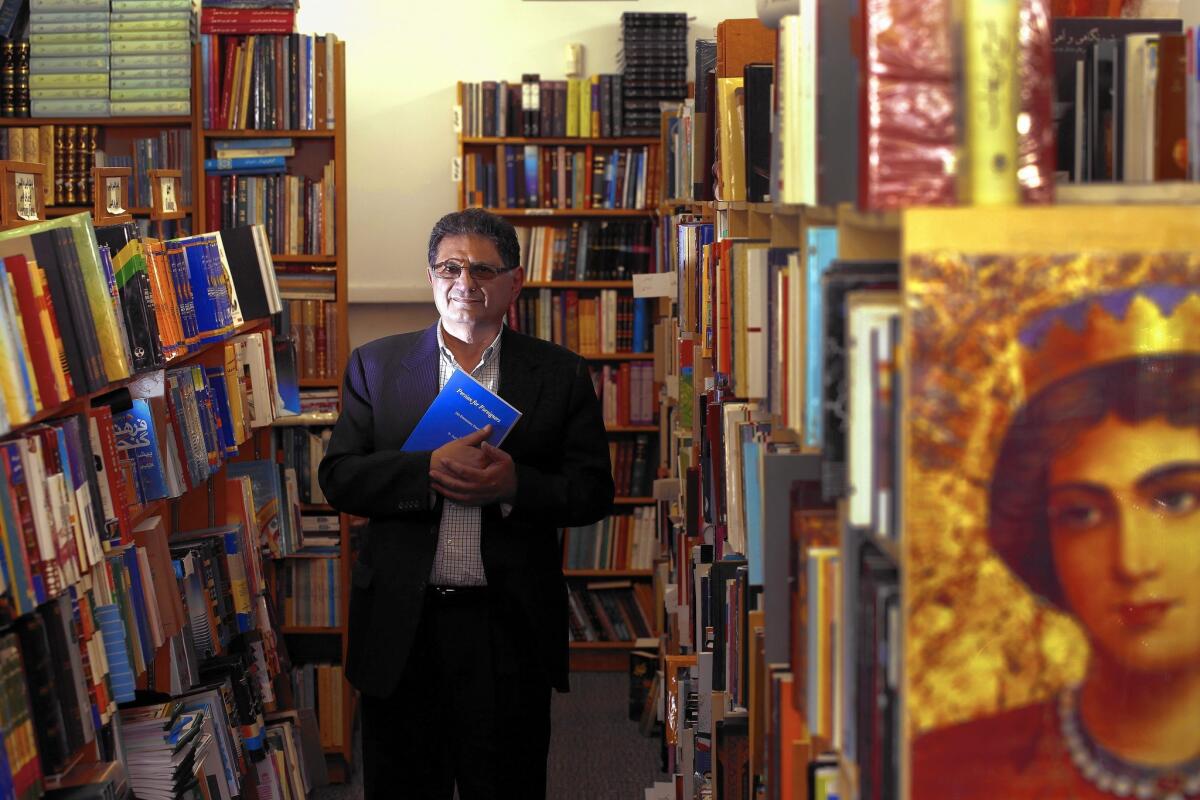

Bijan Khalili, 64, owner of the Ketab Corp. bookstore in Westwood, has a section for books banned in Iran because they promote a “dispassionate look at religion.”

The scene inside the bookstore in Westwood could have been a peek into Tehran in the 1960s and ‘70s, before revolution brought Iran under the stern rule of an ayatollah.

Several visitors filed in on a weekday evening for a poetry reading. They sat just steps from the “prohibited books from Iran” section of Ketab Corp. Back in the 64-year-old shop owner’s homeland, those books could get a person killed for promoting a “dispassionate look at religion,” Bijan Khalili said.

The visitors, mostly Iranian exiles, were here to listen to the words of someone who took dispassionate views. Fereshteh Malekfarnoud laughed nervously before coming to the microphone to call people to either read their own poems or the works of feminist poet Forough Farrokhzad, an influential writer and iconoclast who passed away in 1967.

Mahmood Safarian, 78, read a poem he wrote called “The Lost Homeland.”

I know not how to find her,

The land of lights,

Mother of a million memories,

Home of bright stars.

The intimate, monthly meetings were a way to “vent out and share our deepest thoughts with the people around us,” writer and researcher Jafar Jamshidian said later. “We don’t judge. We listen.”

During the gathering, some made statements defending Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi, who had been deposed when revolution broke out in 1979, while others made pointed political statements. The increasingly serious mood was broken when one elderly woman was asked to speak about Farrokhzad.

“I met her father once who told me Farrokhzad was a lesbian,” she blurted out.

Silence descended for a few beats, before people started talking again. Malekfarnoud told the woman she was confusing the poet with another writer, before gently adding, amid good-natured laughter: “We should be focusing on the art, rather than the artist’s sexual orientation.”

The fact that these conversations can even take place is a stark contrast to the land that those gathered loved but felt compelled to flee.

Many Iranians came to the United States either before, during or after the 1979 revolution. There are hundreds of thousands of people who trace their roots to Iran in the U.S., with L.A.’s Westside and the San Fernando Valley harboring a large population. Thus the community’s nickname: Tehrangeles.

They are Muslims, Jews, Christians, Baha’is.

Mohammad Behrooz, 50, who works with the disabled, left Iran to study in the U.S. and never left. He spoke about eking out a living in the U.S. “It is a tough life. I have been living here for 35 years now, and haven’t gone on a real vacation for the past 20, so you can imagine how tough it might be,” he said.

He came to read and listen to poetry, but like others, Behrooz had an opinion about the nuclear talks between the government of the land of his birth and six international powers, including the U.S.

“It’s all about money and power at the end of the day,” Behrooz said. “It seems more of a deal between the governments than the people.”

Khalili, the bookstore owner, was a student who used to deliver fiery speeches at Tehran’s National University during the revolution that brought Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to power. He continued to speak up but was arrested in 1980 and taken to a prison that mostly housed political prisoners.

“I was kept there for 11 days, and that’s enough time for anyone to reconsider a few things in life,” Khalili recalled. “I was not tortured physically. But I was under immense pressure by knowing that like many other prisoners before me, I might be executed without a trial.”

Less than a year after being released, he and his wife fled to the U.S. with 10 of his favorite books.

“Those were the first books I kept in my new shop when I came here,” Khalili said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.