‘We don’t feel OK here’: Detainee deaths, suicide attempts and hunger strikes plague California immigration facility

The Adelanto immigration detention center has been plagued with complaints. (Aug. 8, 2017)

Alexander Burgos Mejia was in his bunk at the Adelanto Detention Facility on a Tuesday evening in July when he heard a guard scream.

Walking into a common room, Burgos Mejia saw a man hanging from the second floor with a bedsheet around his neck, he recalled in an interview. A female guard was trying to lift the man, and Burgos Mejia ran to help before other officials arrived and cut the man down, he said.

The July 11 incident was the fifth report of an attempted suicide at the immigration detention center since December, according to San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department 911 call logs obtained by The Times through a public records request.

The incident unnerved Burgos Mejia, 28, who came to the U.S. earlier this year from Honduras, fleeing gangs and seeking asylum, and has been detained since.

“I think doing something like that is something that has crossed the mind of all of us who are locked up here,” he said.

As soon as he arrived at Adelanto, Burgos Mejia said, he felt like he was treated like a criminal, not a refugee.

“It’s the most horrible [feeling]” he said. “From the moment that they chain you up from your feet and hands.”

We don’t feel OK here. We’re in danger here. We’re in the middle of a hurricane here.

— Adelanto detainee Omar Rivera Martinez

Government officials say the Adelanto Detention Facility is subject to “rigorous operating requirements” and is tightly monitored to ensure those standards are met. When problems are identified, they are promptly addressed, officials say.

But complaints about the facility have grown particularly loud this year following the suicide attempts and three deaths since March, with multiple hunger strikes by detainees.

*

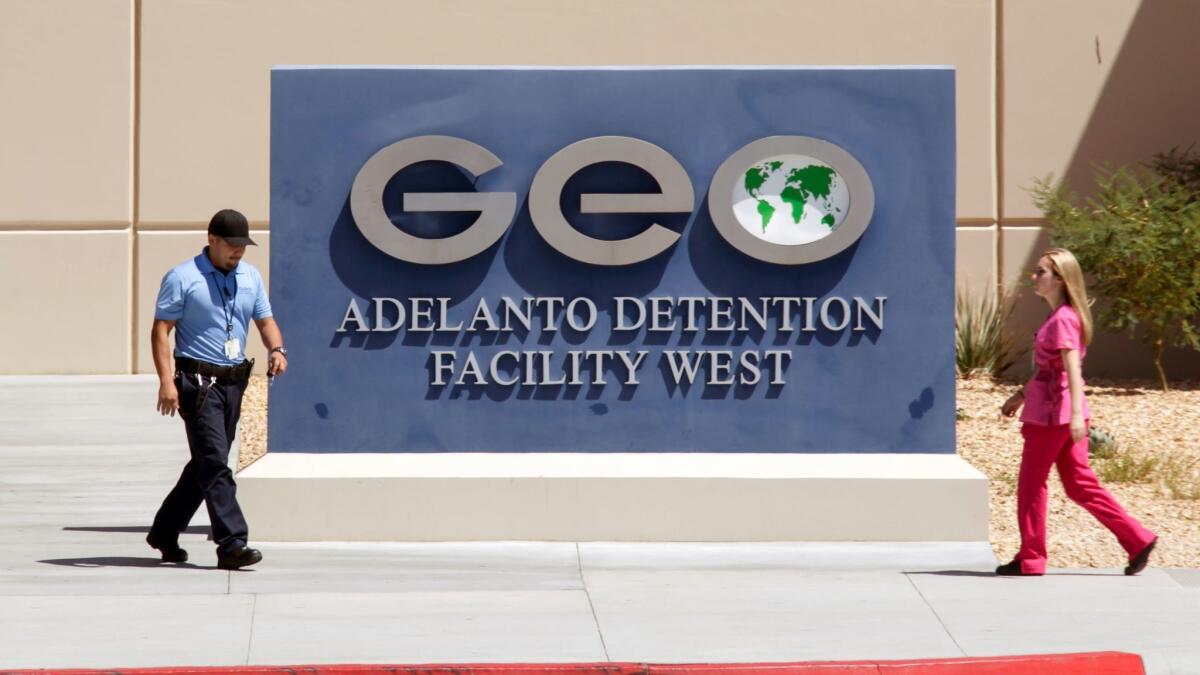

Located in the high desert 85 miles northeast of Los Angeles, the Adelanto Detention Facility can house nearly 2,000 men and women. Officials say more than 73,000 detainees have passed through since it opened in 2011.

Among those held there are asylum seekers, people caught in immigration sweeps and those identified by authorities as potentially deportable after landing in jail. Some have lived in the U.S. for decades, others were sent to Adelanto soon after crossing the border.

The GEO Group, which operates dozens of private prisons and detention centers around the country, owns and operates the facility. GEO Group receives a fee of up to about $112 per day per detainee from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, with the city of Adelanto serving as a go-between.

Detainees and advocates have long complained of medical neglect, poor treatment by guards, lack of response to complaints and other problems. Government inspectors have also noted significant deficiencies at the facility — often related to medical care.

The Times interviewed detainees and their lawyers and advocates, and examined local law enforcement reports, city records and federal reviews dating to 2011, when the facility opened.

In November 2011, an ICE contractor conducting an annual review faulted the facility because “medical officials were not conducting detainee health appraisals within 14 days of arrival, and registered nurses were performing health assessments” without proper training or certification.

Ten months later, a report by ICE’s Office of Detention Oversight found that many requests for medical care were delayed and medical records were not promptly reviewed.

That report also said that the death of detainee Fernando Dominguez Valdivia in March 2012 followed “egregious errors” by medical staff and could have been prevented.

In 2014, another report by the Office of Detention Oversight found Adelanto deficient in 26 areas — including 16 related to the facility’s efforts to prevent and intervene in sexual abuse cases.

After the 2015 death of Raul Ernesto Morales-Ramos, inspectors again found fault with Adelanto.

In the months before he died, Morales-Ramos submitted two complaints to Adelanto officials.

“To who receives this, I am letting you know that I am very sick and they don’t want to care for me,” he wrote in one. “The nurse only gave me ibuprofen and that only alleviates me for a few hours. Let me know if you can help me. I only need medical attention.”

Morales-Ramos had been detained since his 2010 arrest on a warrant issued in El Salvador for conspiracy involving aggravated homicide.

His case persisted for years, and he was transferred to various detention centers until landing at Adelanto in May 2014. He complained throughout his detention of gastrointestinal and other problems and was given pain relievers and medicine for constipation and diarrhea.

Eventually, a doctor who examined him found an abdominal mass that was “the largest she has ever seen in her practice,” according to the review conducted after his death. Based on its size, the tumor had likely been present for months.

The report on his death, prepared by the Office of Detention Oversight, said Adelanto failed to provide Morales-Ramos with timely and comprehensive medical care, among other lapses.

ICE officials declined an interview request.

In a written response to questions, agency spokeswoman Virginia Kice said detention centers have undergone reforms in recent years to ensure “that those in ICE custody receive timely access to medical services and treatment.”

Those reforms include assigning medical coordinators to the agency’s field offices who can closely monitor complex cases, Kice said. Immigration officials have also simplified the process for authorizing detainee healthcare from outside providers, she said.

Pablo Paez, a spokesman for GEO Group, also declined an interview request.

In a statement, he said “the Adelanto Detention Facility has a long-standing record providing high-quality, culturally responsive services, including comprehensive around the clock medical care, in a safe, secure, and humane environment that meets the non-penal, non-punitive needs” of immigration detainees.

“We take all reviews and audits with the utmost seriousness and when necessary implement prompt corrective actions,” Paez said.

He said that during its most recent annual audit the facility was found to be “in compliance with 100% of the mandated ICE standards.” He did not provide a copy of that report. The Times filed a Freedom of Information Act request for copies of all recent inspections of the Adelanto facility in early June, but they have not yet been provided.

*

Attorney Mayra Gamez, who has represented dozens of Adelanto detainees in their immigration cases, said she often finds herself also acting as a medical advocate — pushing for their access to doctors and follow-up care.

“There’s times when they do finally see someone and it’s not a doctor, it’s an RN or some other nurse and they’re just given Ibuprofen or told it’s nothing,” she said.

“Sometimes they agree to [deportation] because they’re afraid of just dying in a detention facility after multiple attempts at seeking help or getting care,” Gamez said.

Since Morales-Ramos’ death in 2015, four others have died at the facility.

Two days before Christmas in 2015, Jose Manuel Azurdia-Hernandez, 54, of Guatemala, died of a heart attack, according to ICE.

In March of this year, Osmar Epifanio Gonzalez-Gadba, 32, of Nicaragua, died six days after he was found hanging in his cell.

In April, Sergio Alonso Lopez, 55, of Mexico, died days after he was taken to the hospital for vomiting blood. Immigration officials said he had a history of serious medical issues. The preliminary cause of death was internal bleeding.

And in May, Vicente Caceres-Maradiaga, a 46-year-old Honduran, died in an ambulance on the way to the hospital. The preliminary cause of death was listed as acute coronary syndrome, immigration officials said in a statement.

While any in-custody death is a cause for concern, the numbers should be considered in context, Kice said.

“Notably, Adelanto experienced no in-custody deaths in fiscal years 2011, 2013, 2014, and 2016,” Kice said. Only one detainee has died as a result of a suicide attempt, she added, a reference to Gonzalez-Gadba.

When it comes to suicide prevention, Kice said, detainees are screened upon admission and “immediate attention is provided to detainees who present a danger or an imminent risk to themselves.”

*

In early July, in a white brick courtroom behind three locked doors inside the Adelanto facility, asylum seeker Omar Rivera Martinez faced Immigration Judge Jose Peñalosa.

Peñalosa spent several minutes explaining the man’s rights. But Rivera Martinez wanted to tell Peñalosa what happened this summer, when he and eight other detainees announced a hunger strike to protest conditions inside Adelanto.

“The GEO officials beat us and sprayed us with gas, and I don’t think that’s right,” Rivera Martinez told the judge.

Rivera Martinez pointed to his mouth, where he had a gap in his teeth, and his nose, which crooked to the left, to show Peñalosa damage he alleged was caused by guards.

Attorney Nicole Ramos told the judge she was struggling to communicate with Rivera Martinez because the facility had blocked her phone number. (ICE officials say they sometimes block phone numbers for security reasons.)

Peñalosa said he would take note of the complaints. But he also explained to Rivera Martinez that his court is charged with deciding immigration cases, not resolving problems within the facility.

Rivera Martinez came to the U.S. this spring in a caravan with dozens of asylum seekers from Central America.

He said he fled El Salvador after a gang killed his brother and kidnapped him, his wife and teenage daughter when they witnessed the slaying. After the family escaped, Rivera Martinez said, he learned that the gang had occupied his house.

“I can’t return home anymore,” he said.

Nine asylum seekers from the caravan reunited after finding themselves detained at Adelanto and soon grew frustrated about their treatment.

“I would never wish this place, Adelanto, on anyone,” said group member Jose Cortez Diaz, of El Salvador. “The mistreatment is just too much.”

The group began a hunger strike and wrote a letter to officials outlining their demands. They included reduced bond, new uniforms — particularly new underwear — more time for religious services, paperwork in their native languages, clean water 24 hours a day and better food.

During breakfast on June 12, they attempted to hand the letter to a guard and asked to speak with someone who would hear their complaints. As more guards arrived, they linked arms and refused to leave.

Rivera Martinez and several others say they were showered with pepper spray and beaten, resulting in the injuries Rivera Martinez showed the judge.

Ramos, the attorney, filed a complaint with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s Office for Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, asking it to investigate “the brutal attack of these men.”

Kice, the ICE spokeswoman, said the situation posed a danger to staff and other detainees.

“Despite repeated orders from security personnel, several of the men continued to physically resist commands to submit to mechanical restraints,” Kice said in an email. “The officers applied the necessary degree of force to remove the resisting detainees from the residence unit and temporarily transfer them to a restricted housing area.”

None of the men was injured, Kice said, adding that review found “proper policies and procedures were followed.”

After the protesters were allowed back into the general prison population, they began another hunger strike, which lasted several days.

In early July, the group launched a third hunger strike, which lasted about 72 hours and included dozens of additional participants, detainees and their supporters said.

In a letter to officials, they said they wanted their bond amounts to be reduced so they could leave Adelanto while fighting their cases for asylum. Several asylum seekers said their bond was between $15,000 and $35,000.

“We need for them to please let us out of here immediately,” Rivera Martinez said. “We don’t feel OK here. We’re in danger here. We’re in the middle of a hurricane here.”

To read this article in Spanish, click here.

Twitter: @palomaesquivel

ALSO

Chicago to sue Justice Department over threat to strip funds from ‘sanctuary cities’

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.