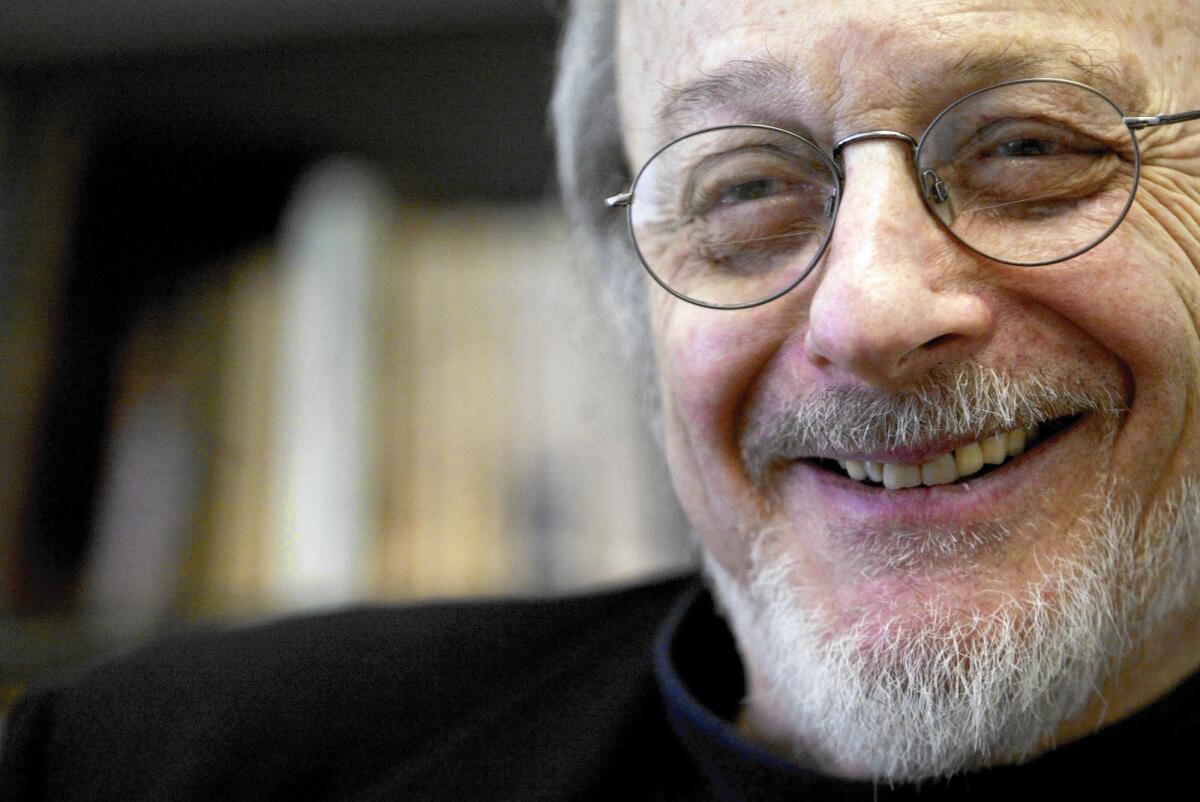

E.L. Doctorow dies at 84; ‘Ragtime’ author turned history into myth

“Ragtime” was E.L. Doctorow’s breakthrough novel. It takes place in New York during the Gilded Age, offering a fabric of real and fictional characters.

E.L. Doctorow, an elder statesman of American letters, whose best-known works weaved historical figures such as Harry Houdini, Emma Goldman and Julius and Ethel Rosenberg into imaginative retellings of a distinctly American tale of class, race and fragile truths, died Tuesday in New York City. He was 84.

The cause was complications of lung cancer, said his son, Richard Doctorow.

The author of a dozen books, including “The Book of Daniel,” “Ragtime,” and “Billy Bathgate,” he was an imposing talent, who came of age with a vivid generation of American writers. His contemporaries include Joan Didion, John Updike and Philip Roth, but unlike them he was not content to write with a personal filter; he had a broader literary mission in mind.

“Every book has its own voice,” Doctorow told The Times in 2006. “I think there’s a kind of ventriloquial thing that goes on when I write. I don’t ever want to hear my own voice; it’s one of the worst things that can happen.”

This explains his range, both in terms of subject and sensibility. His first novel, “Welcome to Hard Times” (1960), was intended to subvert the conventions of the Western genre, while his second, “Big as Life” (1966), brought the same approach to science fiction.

“Ragtime” (1975) was Doctorow’s breakthrough, but it was not his first great book. “The Book of Daniel” (1971), which fictionalized the Rosenberg atomic espionage case through the eyes of the children they had left behind, moved back and forth from the Red Scare to the divisions of the 1960s, representing in many ways a coming-of-age story for the culture at large.

Later, he would revisit these themes in such works as “Billy Bathgate,” a Faulknerian portrait of gangster Dutch Schultz through the eyes of a Depression-era Bronx street urchin that won a PEN/Faulkner Award and a William Dean Howells Medal; and “The March” (2005), a re-imagining of Sherman’s march as a homegrown Grand Guignol, which won the National Book Critic’s Circle Award for fiction as well as the Pen/Faulkner.

Edgar Lawrence Doctorow was born in New York City on Jan. 6, 1931, and grew up during the Depression. His musicologist father, David, and pianist mother, Rose, named him after Edgar Allan Poe.

He attended Kenyon College in Ohio, which he described as an invaluable training ground for writers where he studied poetry with John Crowe Ransom and students “did literary criticism the way they played football at Ohio State,” he told the Paris Review some years ago.

After graduating from Kenyon in 1952, he spent a year in post-graduate studies at Columbia University. While at Columbia he met Helen Setzer, a writer. They married in 1954.

Along with his wife and son Richard, he is survived by daughters Jenny and Caroline and four grandchildren.

Doctorow wrote plays while serving in the Army. After completing his military service, he went to work as a script reader at Columbia Pictures, where he was forced to appraise “one lousy Western after another,” as he told the Miami Herald in 1975.

Convinced he could do a better job, he wrote a short story that became the first chapter of “Welcome to Hard Times,” a Western parody in which, he told the Los Angeles Times in 2006, “the bad guy just wipes out this town.”

Noting the agility with which the young author grappled with a philosophical quandary involving man and evil, the New York Times praised the novel as “taut and dramatic, exciting and successfully symbolic.”

He continued to play with literary traditions in his next novel, “Big As Life,” his satirical sci-fi tale involving naked human giants in New York harbor. He later disavowed the novel as the worst book he ever wrote.

His third novel, “The Book of Daniel” (1971), trod deeply into one of the most contested episodes in American history.

While struggling with how to tell the story, he accepted a post at UC Irvine, in 1968, that turned out to be a propitious move.

He sought to write about an explosive time, when suspected Communists were being exposed and, in many cases, prosecuted, or worse, put to death, as the Rosenbergs were.

“Out of the campuses came something called the New Left, and I began to wonder how it compared with the old left of the ‘30s,” he told the Guardian. “It occurred to me that I could tell the story of this country’s life over a 30-year period by dealing with its dissidents. And I realized that the Rosenbergs could be the fulcrum. Everything snapped together.”

New Republic critic Stanley Kauffmann proclaimed it “the political novel of our age, the best American work of its kind that I know since Lionel Trilling’s ‘The Middle of the Journey.’” Jane Richmond in Partisan Review called it “a book of infinite detail and tender attention to the edges of life as well as to its dead center.”

“Ragtime” (1975) takes place in New York during the Gilded Age, offering a fabric of real and fictional characters. Of the latter, the main figure is Coalhouse Walker Jr., a black musician victimized by racism. Doctorow “turns history into myth and myth into history,” Raymond Sokolov wrote in a review for the Washington Post.

The interplay of history and imagination drove much of Doctorow’s work, but his was a perilous undertaking.

“History is the present. That’s why every generation writes it anew. But what most people think of as history is its end product, myth,” he told Paris Review in 1986. “So to be irreverent to myth, to play with it, let in some light and air, to try to combust it back into history, is to risk being seen as someone who distorts truth.”

He was often asked what kind of novelist he was. Some observers wanted to put him in a box with historical novelists. Others saw him as mainly a political writer. Still others labeled him a Jewish novelist.

“I accept any kind of identity,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 2006. “I’m willing to participate in all of them, as long as none claims to be an exhaustive interpretation.”

Times staff writers David Ulin and Ryan Parker contributed to this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.