Vincent Harding dies at 82; historian wrote controversial King speech

Exactly a year before the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down in Memphis, he delivered a speech that alienated ordinarily sympathetic politicians, liberal commentators and even some of his fellow leaders in the civil rights movement.

In a blistering address at Riverside Church in New York City, King denounced the Vietnam War, likened U.S. bombings to Nazi atrocities, and called for unilateral withdrawal. The problems eroding America, he said, were “the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism and militarism,” and as a Christian, he had to “speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation.”

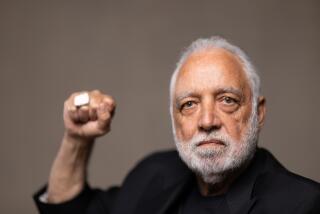

King advisor Vincent G. Harding, a historian and lay minister who wrote what is said to be the Nobel Peace Prize laureate’s most controversial address, died Monday in a Philadelphia hospital from the effects of a heart aneurysm, according to the University of Denver’s Iliff School of Theology, where Harding taught for many years. He was 82.

Years after King’s April 4, 1967, speech, Harding recalled its explosive reverberations. Other black leaders, he said, were concerned about offending President Lyndon B. Johnson, who had pushed through landmark advances in civil rights.

“All the keepers of the conventional wisdom, especially in the New York Times and the Washington Post, simply vilified and condemned Martin,” he said in a 2007 interview with Sojourners magazine. “They spoke about the fact that he had done ill service, not only to his country, but to ‘his people.’”

The Riverside speech — known as “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence” — was pilloried by 168 newspapers, said commentator Tavis Smiley, who produced an hourlong PBS special on it in 2010.

It “led to the demonization of King,” Smiley told the Atlanta Journal and Constitution that year. “The speech caused black leaders to turn against him. It got him disinvited by LBJ to the White House. He couldn’t get a book deal. It’s fascinating, given the adulation and adoration we have for MLK today.”

Harding and his first wife, Rosemarie Freeney Harding, who died in 2004, met King when they traveled from Chicago to Atlanta to continue the civil rights work they had begun in the Mennonite church. Harding became an advisor and friend to both King and his wife, Coretta Scott King, and later served as the first director of what is now known as the King Center in Atlanta.

In 1965, Harding, then chair of the history and sociology department at Atlanta’s Spelman College, wrote an open letter about Vietnam to King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

“I raised the question as to whether or not we could, in conscience, keep still about what was going on in Vietnam,” Harding recalled in 2007, describing the war’s origin as an “anti-colonial struggle.”

King and other black leaders wrestled with the question for two years.

“Down deep within all of it,” Harding said, “was America’s racist attitude, which essentially said, ‘It’s all right, King, for you to talk about colored things but, when it comes to foreign policies, that’s our business. We really don’t want to hear anything from you about it because that’s our business.’”

While some of King’s top advisors tried to dissuade him from delivering the speech, which was also known as “Beyond Vietnam” and “The Breaking of Silence,” his words from the altar were grimly determined: “I come to this great, magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice.”

Born July 25, 1931, in New York City, Vincent Gordon Harding grew up in Harlem and the Bronx, the son of a single mother who worked as a cleaning woman. He received a bachelor’s degree from the City College of New York, a master’s degree from Columbia and, in 1965, his doctorate in history from the University of Chicago. He served in the Army from 1953 to 1955.

His works of history include “The Other American Revolution” (1980) and “There Is a River: The Black Struggle for Freedom in America” (1981).

Of the latter, he wrote that, while offering “a rigorous analysis of the long black movement toward justice, equity and truth … I have freely allowed myself to celebrate.”

He was a senior consultant for the PBS documentary series on civil rights “Eyes on the Prize.”

Harding also taught at Temple University in Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania. He was to deliver the Iliff School of Theology’s commencement address June 4.

Harding’s survivors include his second wife, Aljosie Aldrich Harding; daughter Rachel Harding; and son Jonathan Harding.

The Associated Press was used in compiling this report.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.