Capitol Journal: Brown’s water quest taps forebears’ inspiration, if not their flexibility

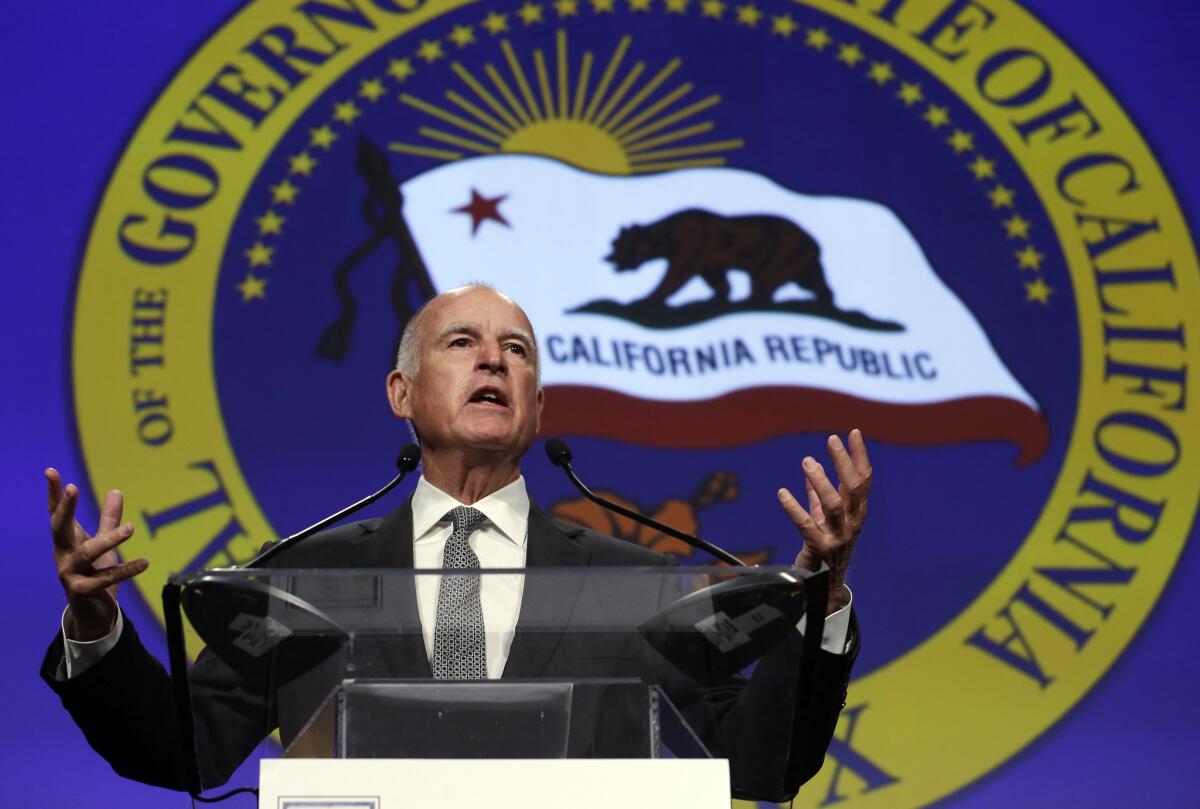

California Gov. Jerry Brown speaks at a gathering of political, business and community leaders at the annual California Chamber of Commerce Host Breakfast in Sacramento on May 28.

Gov. Jerry Brown increasingly seems to be drawing from the past, inspired by his pioneering forebears and comparing their struggles with his own.

They had much tougher lives, he tells audiences. Surely if they could cross the Plains in covered wagons, tame the land and fight mosquitoes, he can dig two big water tunnels and erect a bullet train.

And remember that President Lincoln, Brown sometimes adds, boldly authorized construction of the transcontinental railroad while waging the Civil War.

Never mind that Abe and the railroaders stole much of the Western right-of-way from Indians.

These days, it’s not that easy. Many farmers around Bakersfield are refusing to sell out for high-speed rail. And people in the San Fernando Valley also have begun vehemently bucking the bullet train.

In the bucolic Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, where Brown wants to bore the humongous water tunnels, growers and recreationists are riled up and battling back.

These obstacles are nothing that can’t be overcome by grit, the governor implies.

Speaking to hundreds of business leaders at an annual breakfast in Sacramento last week, Brown dismissed the concept of perfection.

“What we need in the government is to build these big infrastructure projects, take care of the basic needs but don’t attempt to re-create and reinvent the world in some utopian effort to make everything all perfect,” he said. “It’s not perfect. It’s messy. There’s suffering. In the end, we all die. When you’re 77, by the way, that’s a little more imminent than it was when I spoke to you 40 years ago.”

Brown added: “I think it is very good to channel our forebears, who had a much tougher life with a lot less reward, a lot less little pleasures. … It was work and work all the time. But they built it. … And so it’s our destiny and our duty to build on it.”

In that latter comment, the governor probably was thinking of his late father, Gov. Pat Brown. If his dad more than half a century ago could lead California into building a world-class water project over fierce northern opposition and southern apathy, the son believes, certainly he can complete that troubled system with the delta tunnels.

But since the 1960s, environmentalists have witnessed the State Water Project’s ecological damage, especially to the salmon fishery, and also seen that there’s really no quenching of California’s thirst, no matter how many rivers and wetlands are drained.

Perhaps it’s time to expedite our focus on desalination, recycling and more judicious use of water. Also, seriously get going on some much gabbed-about new reservoirs.

Regardless, Brown is on a mission inspired by his family’s past.

When people ask how Brown has changed since he first was governor in his 30s, one answer is that he now shows respect for his forebears.

Back then, he practically ignored his father. And I don’t recall his ever mentioning the pioneers.

Returning to his roots, the governor and his wife, Anne Gust Brown, spent the long Memorial Day weekend in a small cabin he had built on 2,700 acres of isolated family-owned property in Colusa County.

“Right at the very spot where my father’s grandfather started a stage stop and hotel,” Brown told the business leaders. “It’s hot, there are a lot of mosquitoes and when he was there, August Schuckman, … there was no well. They had to collect the water on the roof and put it in a cistern. There was no electricity. … The guy … lived there 35 years, died there at the age of 80.

“I’d get up in the morning — it’s surrounded by very unique mountains — and as the sun comes over, I just kept thinking about this guy, what he went through. … He had to get on a boat in Germany, come all the way over here on a covered wagon.”

The governor’s cabin — basically a crude shelter — also has no electricity. Or even a toilet. There’s a nearby outhouse.

But what was acceptable to people living in the 1800s — or even politicians developing water projects a half-century ago — could be significantly upgraded for life in the 21st century.

U.S. Rep. John Garamendi (D-Walnut Grove), for example, has been trying to push a cheaper, simpler, less land-destructive alternative to Brown’s delta plan. The governor wants to burrow two 40-foot-wide, 35-mile tunnels under the delta, siphoning fresh water from the Sacramento River to southbound aqueducts at a cost of $17 billion.

Garamendi, a former lieutenant governor, advocates using what’s already there: 25 miles of a ship channel that skirts the west side of the delta from West Sacramento. He’d add on a smaller, 12-mile underground pipe to the aqueducts. The water would be fresher, he says, and the cost about one-third of the tunnels.

State water officials have rejected the concept, saying it would harm endangered smelt — what few fish remain — and also interfere with shipping. Garamendi dismisses both arguments and notes only about 30 ships a year use the channel anyway.

“They’re stuck on the tunnels,” Garamendi says. “The governor is a difficult person to talk to. He seems to be digging himself in more firmly.”

It’s admirable that Brown draws strength from his forebears’ guts and resolve. But he should also remember that they were flexible and open to new ideas.

When Great-Grandfather Schuckman returned to Germany to marry, he ditched the covered wagon on his way back to California and sailed around Cape Horn.

Twitter: @LATimesSkelton

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.