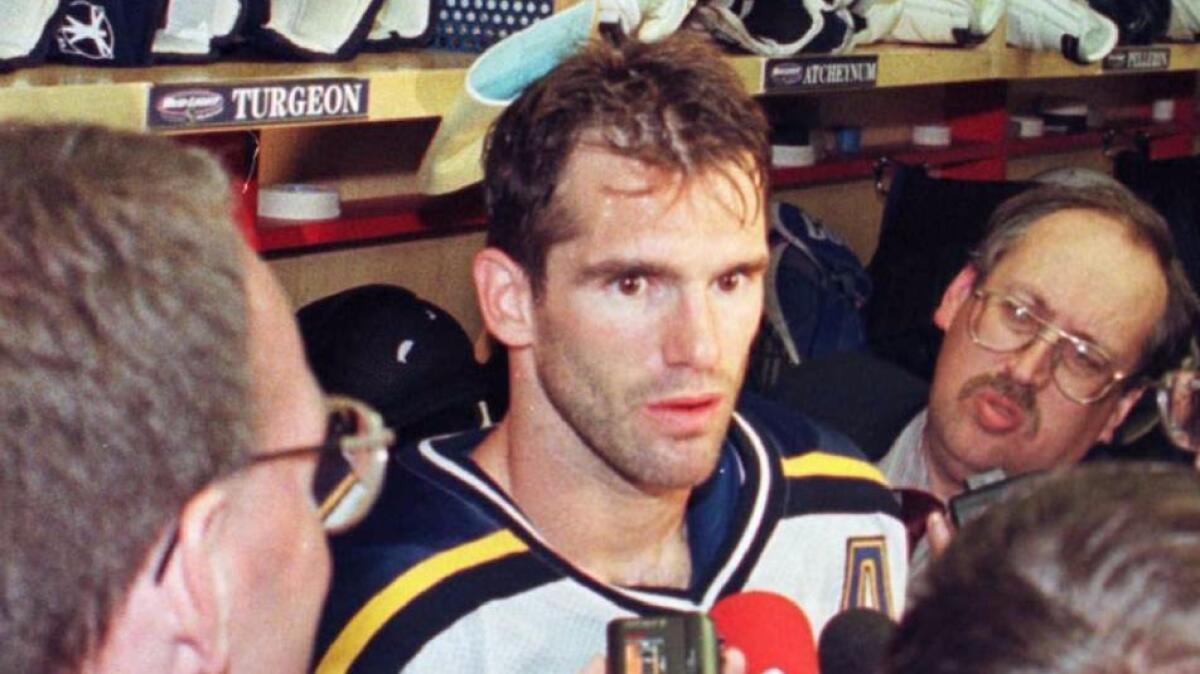

Column: Pierre Turgeon has the challenge of helping Kings develop a more productive offense

The Kings’ stagnant offense could use a Pierre Turgeon-type of player, a big forward blessed with finesse, playmaking skill and a knack around the net.

Although Turgeon is a decade into retirement as a player, he might still be able to help them: he was hired this week to be their first-ever offensive coordinator, in essence hoping he can coax them into producing enough offense to coordinate.

The Kings ranked 25th in NHL scoring in 2016-17 at an average of 2.43 goals per game, a prime reason they missed the playoffs for the second time in three seasons. Turgeon, who stands 38th in career goals with 515 and 32nd in career points with 1,327, can’t score goals for them. He probably can’t teach them to score goals, either. That’s an innate skill.

What they believe he will bring to his first NHL assistant coaching job is a fresh perspective on an old problem and the rare ability to express his ideas in ways players can grasp and execute.

Great players rarely become great NHL coaches; they were guided by instinct, and that’s difficult to put into words.

Luc Robitaille, the Kings’ president and a friend of Turgeon’s since they were rivals in the Quebec Major Junior Hockey League more than 30 years ago, invited Turgeon to the Kings’ development camp a few weeks ago and was impressed at how well Turgeon communicated what he knew and what he learned while watching action and video. That was motivation enough for Robitaille and coach John Stevens to create a position for Turgeon, who will work with players on the ice during practices and watch games from above to provide advice and analysis.

“What he demonstrated to us in our conversations and from everything we know about him from when he was a player is that he can articulate what he saw on the ice,” Robitaille said. “We also know that he isn’t scared to put in the time.”

Turgeon hadn’t sought this job or any other. It found him at the right time, a year after his and wife Elisabeth’s youngest child, Valerie, had left the family’s Colorado nest to play hockey at Harvard. Daughter Alexandra, 24, had returned home but manages on her own; their son Dominic, 21, a 2014 third-round draft pick by Detroit, recently won the American Hockey League championship with the Grand Rapids (Mich.) Griffins. Alexandra’s twin, Elizabeth, a member of the U.S. women’s under-18 national team, died in a 2010 car crash.

Turgeon, who settled his family in Colorado after he ended his 19-season career with the Avalanche, had kept busy coaching his kids and traveling to their games. He was ready for something new, even if he didn’t initially realize it.

“It was all about me being on the road and traveling and it was all about my job and then I had the chance to be around the kids, so I did that for many years,” he said in a phone interview. “I just didn’t want to start working right away. But talking to my wife, she said, ‘You know what, they’re all gone.’ Everyone is gone except my oldest one. … This is a new chapter, a new challenge, and my wife said, ‘Do it.’ So we’re going to be moving there. It’s a great challenge and I’m looking forward to it.”

He plans to spend a lot of time analyzing video of opponents’ plays and tendencies, looking for the smallest crack or quirk the Kings can exploit. “There’s things you can teach, or make other players realize the time and space they have to create,” he said. “Or if [opponents] are very aggressive as far as the power play or penalty killing, bring ideas on where can you relieve the pressure by putting the puck in areas where you’re not going to have as much pressure, if that makes sense.”

He also plans to lead drills designed to refine players’ skills. “You can work on targets, or shooting quick release, or shooting and finishing on the left side or right side of your legs,” he said. “You repeat this in practice, you get in a game situation and you’re reacting to what you have in front of you without thinking about it.”

The NHL has changed since Turgeon was at his peak, now driven by smothering defenses and athletic goaltenders. He scored 58 goals and 132 points in the 1992-93 season but finished in a tie for fifth in goals and a tie for sixth in points. Only once in the last eight season has a player scored 60 goals — Tampa Bay’s Steven Stamkos had 60 in 2011-12— and Edmonton’s Connor McDavid won the scoring title this season with 100 points.

“It’s a different game as far as the neutral zone, as far as defensive play and the way they’re structured defensively. And everyone’s doing it,” Turgeon said. “If you want to score today, you’ve almost got to hit the post and go for that rebound on the right side or the left side and create traffic in front of the net.”

Well said. The next step is for it to be well done. That’s the tricky part.

Follow Helene Elliott on Twitter @helenenothelen

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.