Juan Carlos Osorio may have been caught sleeping on latest attempt at innovation

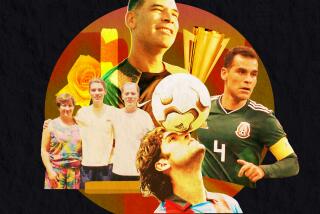

Juan Carlos Osorio is not your typical soccer coach.

Serious and professional, he has played the game on two continents and coached it on three, studying the sport at a pair of American colleges and earning a diploma in Science and Football from Liverpool John Moores University.

Resourceful and obsessive, he worked for a time as an undocumented immigrant, doing odd jobs for low pay to continue his soccer education in the U.S., then stood on a table to peer over a fence and watch Liverpool’s closed training sessions after moving to England.

So the Colombian did not get his job as manager of the Mexican national team through good luck or good contacts. He earned it with a slow, methodical climb during which he pored over soccer tomes in two languages and debated tactics with both accomplished coaches and with those who had accomplished nothing, all the while scribbling notes in the journal he always keeps at hand.

It’s a singular path that has taught him to trust science, trust his instincts and not to fear exploring the road no one else has taken.

In a couple of otherwise pedestrian discussions of soccer last week Osorio, who speaks with both conviction and a mischievous twinkle that makes you wonder if it’s all a joke, veered off to talk about the frontal lobe and the role low levels of alcohol consumption may have played in getting Iceland to the World Cup.

“I am a man of the world,” he offered without prodding.

Maybe. But in soccer terms Osorio, 56, is a “tinkerer,” a label given to tireless experimenters unable to leave well enough alone. In a sport bound by tradition, it’s a label that reads like a scarlet letter — and one Osorio wears as a badge of honor.

He is a proponent of squad rotation, soccer’s version of a platoon system in which he alters lineups for tactical purposes, to keep players fresh and to increase versatility. It’s a controversial approach that has won him few fans in Mexico — where, as a Colombian, he had few supporters anyway — but it has made him Mexico’s most successful national team coach in the last 30 years.

“We have more players playing in two or three positions, which makes the team stronger,” he said after Friday’s 3-0 win over Iceland in a World Cup tune-up. “And we are adapted to play against different styles of football.”

That’s hardly the extent of Osorio’s tinkering though.

After losing defender Carlos Salcedo to ligament damage in his left shoulder during last summer’s Confederations Cup, Osorio studied information from the 2014 World Cup in an effort to learn how to lessenthe impact of injuries.

“The conclusion is that in each game there are about three injuries. And the soft-tissue injuries, basically whoever gets [them] is out for the whole tournament,” he said.

So Osorio persuaded the Mexican federation to expand his medical staff by adding a masseuse, a physical therapist and a chiropractor.

The next innovation, Osorio said, will be the addition of a sleep coach, an assistant who will help his players maximize their rest, adjust to time changes more quickly and learn to sleep better.

“I think this is going to be the new thing in the future,” said Osorio, who read about it in a book this winter and already has three candidates for the job.

But while that’s a radical new wrinkle for the Mexican national team, it’s an idea that has been gaining popularity in several sports for nearly a decade.

A landmark 2011 Stanford study on the effects of rest for college basketball players found that increased sleep led to faster sprint times, a nearly 10% improvement in shooting accuracy and quicker reactions. Other researchers reported similar findings, leading several NBA and NHL teams to eliminate some morning practices on game days in favor of extra sleep.

“Twenty years ago, it was all about who could play the best with poor sleep and nutrition,” said Brandon Marcello, a high-performance strategist who works with professional athletes and the U.S. military, and is one of the researchers who produced the 2011 Stanford study. “Now teams are paying attention to [sleep] and making it a priority.”

It’s become so big, in fact, Fatigue Science, a Vancouver-based company that measures the effect of fatigue on performance, has worked with more than 50 teams in several professional sports on planning team schedules for long road trips.

Osorio, now among the converted, said Mexico will take a sleep coach with it to Russia for this summer’s World Cup. However, Marcello said, this is one innovation Osorio may have been too late in embracing.

“With just under three months remaining, all [a coach] could do is make recommendations as to travel schedules, adaptation strategies and the like,” he said. “While those things are important and can help, there is far more to it that. It’s about evaluation, education and implementation.”

Osorio is going to give it a shot anyway because…well, why not?

“When you open yourself,” he said “then you learn a lot.”

Follow Kevin Baxter on Twitter @kbaxter11