So you want to be a sommelier?

Massage therapists, bellmen and valets aren’t the people you’d expect to sit through a rigorous 10-month wine course. But in Southern California, the race is on to gain certification as a sommelier and get a foot in the door of one of today’s hottest careers.

Los Angeles has long struggled to attract top sommeliers. But now as the area’s restaurant scene matures and restaurateurs elevate wine service to match the standards of their cuisine, salaries for sommeliers are soaring. And a new generation of ambitious wine professionals eager for a leg up in a suddenly competitive industry is seeking membership in the Court of Master Sommeliers, an elite organization that selects its members through a series of rigorous examinations.

FOR THE RECORD:

Master sommeliers: A Dec. 12 article on the local community of sommeliers stated that there are no master sommeliers in Los Angeles County. It did not mention Elizabeth Schweitzer, a master sommelier living in Monrovia. She works as an educator and writes reviews for Wine of the Month Club. —

It’s attracting more than just seasoned pros such as the sommeliers who meet weekly at Wolfgang Puck’s Cut restaurant in Beverly Hills to study for the tests. Thanks to employer encouragement and subsidies, rank-and-file hospitality workers are cracking the wine books as well.

The evolution of a serious regional wine culture relies on senior sommeliers willing to teach those less experienced. An entry-level course with 40 students at Disneyland’s Napa Rose restaurant looks ultra-democratic. But the highly politicized Court of Master Sommeliers invites just some students, not all, to advance through the process. Even then, the London-based organization’s final exam has a 97% failure rate.

That elitist approach has had cachet in San Francisco, Las Vegas and, to a lesser extent, New York City. But not in Southern California, where self-taught sommeliers have been the heart of an eclectic and informal wine culture. That lack of formal training can lend an appealing, unpretentious ambience to restaurant wine service.

Yet, as diners experience all too often, it has also made it possible for hobbyists with no more than a subscription to Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate and the ability to babble to masquerade as sommeliers.

The final stretch

NOW there is a critical mass of potential master ommeliers in the region. As many as a dozen local wine professionals plan to take the final exam when it is offered in February.

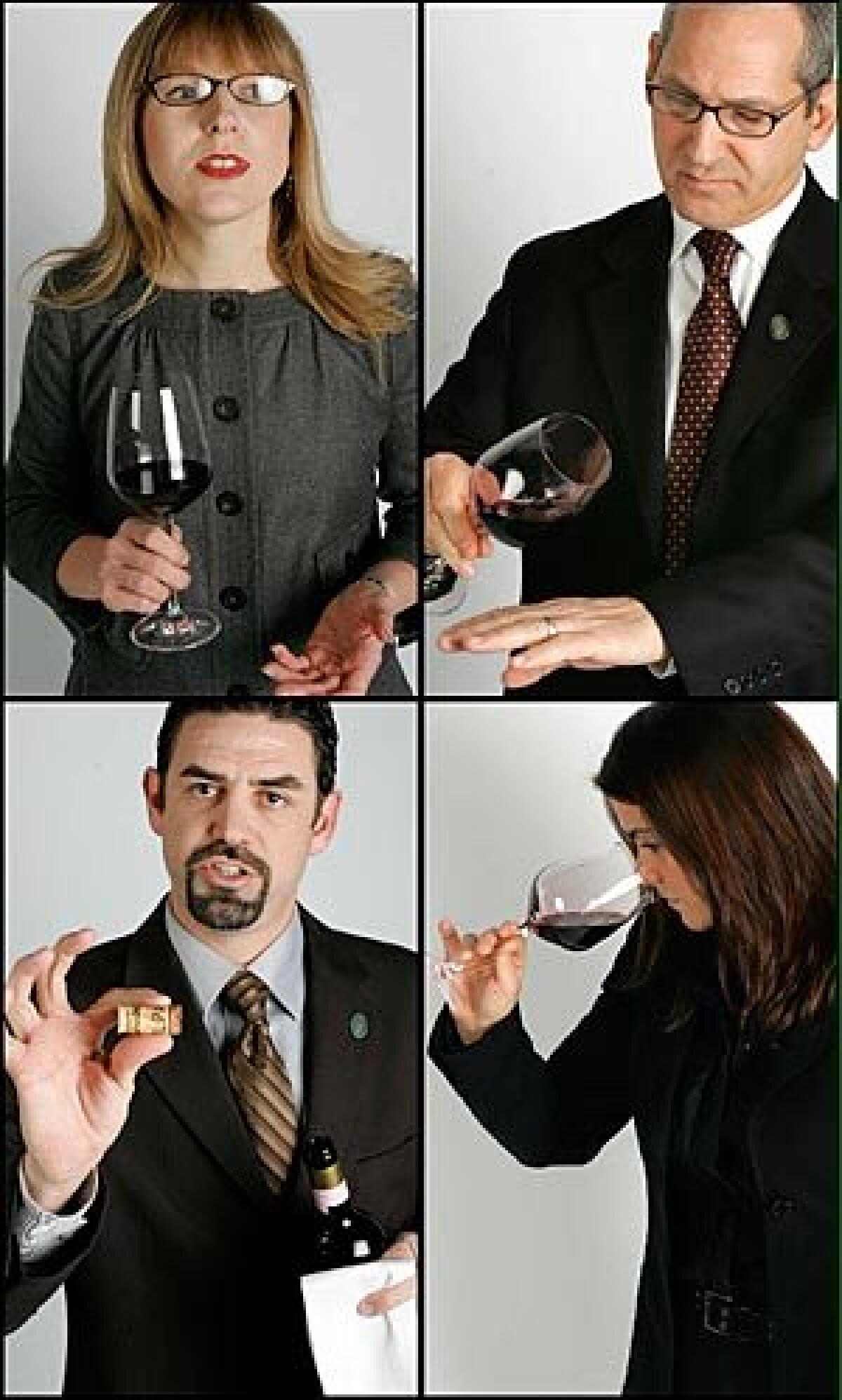

The four experienced sommeliers who study together at Cut -- Mark Mendoza from Sona Restaurant, Cara Bertone with Water Grill, Paul Sherman of Valentino and Dana Farner with Cut -- range in age from their late 20s to early 50s and have each decided to push their expertise to the next level.

Los Angeles County has been home to only an occasional master sommelier and has none now. So these four help one another. The men have passed the advanced-level test and are preparing for the final exam, while the women are working toward their advanced certification, the third step in the four-step process.

Orange County boasts two master sommeliers. One, Michael Jordan, general manager of Disneyland’s Napa Rose restaurant at the Grand Californian Hotel, passed the test last month. As he worked his own way through the program, Jordan coached 280 Disneyland employees through the entry-level sommelier test. Of that group, 50 have advanced to intermediate and six have passed the advanced level.

At Montage Resort & Spa in Laguna Beach, wine director Christopher Coon has taught the entry-level course to 76 of the hotel’s employees while he’s been studying for February’s final exam. The MS certification program is “more meaningful than ever,” says Kevin O’Connor, wine director of Spago in Beverly Hills. O’Connor never bothered to earn his master sommelier certificate, he says, because the program was little known in the 1990s when he was building his career.

But now, when he hires young sommeliers, O’Connor says he looks for people who have had formal MS training. “There is so much heat around wine these days,” he says. “There needs to be some standard to judge whether one wine person is better than another, some bar to clear.”

The Court of Master Sommeliers, founded in 1969, is the best known and among the most highly regarded wine service educational organizations. It established an American chapter in 1986, and 87 of the 158 master sommeliers certified worldwide have been Americans.

It can take a sommelier years to matriculate through the four levels of the master sommelier program. The introductory course ($495 for the test) is designed for restaurant servers and anyone who needs a basic understanding of wine. The intermediate ($295) and advanced level tests ($895), which require extensive memorization and experience serving wine, must be passed before a candidate is eligible to be invited to take the final exam ($800).

With its extraordinary failure rate, candidates expect to take the final test several times. When Montage’s Coon sits for the February exam, it will be his sixth attempt. Napa Rose’s Jordan passed on his fourth try.

Factoring in cost

THE costs add up. And that doesn’t include the expense of studying and traveling to wherever the final exam is being held, usually in San Francisco, Napa Valley or Sonoma County. “I have never been willing to calculate the costs,” Coon says.

Convinced that a wine-savvy staff distinguishes their resorts, Disney and Montage pay for their employees’ tests, as well as the cost of bringing in master sommeliers to teach classes. Most independent restaurants can’t afford to do the same.

That leaves people like Sona’s Mendoza to foot much of the cost himself. Studying to take the exam in February, he says he isn’t concerned about the service aspects of the test, even the arcane cigar-lighting rituals. He has memorized the world’s wine regions and all of the obscure wine grape varieties.

But the blind taste test will be tough, he says. It requires that he accurately describe the wine in a glass, naming the varietal, region and vintage while explaining his rationale for those conclusions -- and that he do so in four minutes. The right answers with the wrong rationale earn an F. The wine can be from any established wine region in the world.

So every Thursday morning, Mendoza meets with his study group at Cut to practice blind-tasting wines, each person bringing wines for the others to taste. “You can’t do this by yourself,” says Valentino’s Sherman.

At a recent practice session, Sherman was on the money when he guessed a red wine was a cool climate Pinot Noir from 2005. (It was an Ojai Vineyard Pinot Noir from Santa Maria.) Cut’s Farner tasted a red wine that she thought could be a Sangiovese from Tuscany or a Cabernet Franc from the Loire Valley. “It smells like an overflowing leaf bin set out in the sun on a hot day,” she said. Then, correctly, she declared it a 2005 Chinon, a Cabernet Franc from the Loire Valley.

There is plenty of private complaining about the perceived politics of these tests. To some, it appears that the pass rate of 3% is artificially low. Swelling the ranks of credentialed master sommeliers could lessen the value of being a member of the club.

As a result, some sommeliers are attracted to other credentialed wine education programs. Pieter Verheyde, Bastide’s wine director, prefers the analytical approach of the Institute of Masters of Wine in London. That test has less of an emphasis on memorization and involves more theory and essay writing.

The Wine & Spirit Education Trust, another London-based organization, is considered the training program for the institute and can be taken as a correspondence course.

Noel Baum, a sommelier working under Mendoza at Sona, is taking classes through the International Sommelier Guild, an educational organization based in Coral Springs, Fla.

Valentino’s Sherman began teaching a wine program at the California School of Culinary Arts in Pasadena after completing a yearlong course for college credit at the UCLA Extension that graduates 20 or more students a year.

Matthew Straus, wine director at Wilshire restaurant in Santa Monica, went to cooking school to focus on pairing wine with food.

“Some of the best palates I’ve ever encountered don’t have an MS,” Spago’s O’Connor says. “In the end, it’s just a test. Passing it can represent little more than an ability to study. And it sure doesn’t mean you can run a wine program or have any sense of wine.”

Salary potential

BUT it does mean you will earn more. “If you have the credential, you can command the money,” says Steve Morey, who earned his master sommelier credentials working in San Francisco restaurants and now owns a wine distribution company in Las Vegas. “No one will question your wine knowledge.”

Five years ago, a top sommelier in Los Angeles could earn, perhaps, $60,000 a year, according to local sommeliers. Today, those jobs often pay $100,000 or more. A master sommelier not only has an edge in getting those jobs, but also can take advantage of opportunities in wine distribution, restaurant management and even winemaking.

Raj Parr manages the wine program for Michael Mina’s group ofrestaurants and travels the world buying wines. A central figure in the San Francisco wine community, Parr never earned his master sommelier certificate, but is often cited as a role model by Los Angeles sommeliers because of his mentoring of junior sommeliers.

Parr says the wine community in L.A. is becoming much like that of San Francisco. “It’s supportive, collegial,” he says. “The learning curve has been incredible in Los Angeles.”

At this point in his career, Parr says, it would be redundant for him to become a master sommelier. But the training he received from Larry Stone, one of America’s first master sommeliers and now the general manager of Francis Ford Coppola’s Rubicon Estate, made the difference in his career. “What matters is discipline and ethics. You have to learn, taste and study, which you do with the MS,” Parr says.

Stone and the other master sommeliers in San Francisco had a seriousness of purpose that set the tone for the city’s wine culture, Parr says. The great news for diners is that the growing ranks of master sommeliers will do the same for Los Angeles. “There is a sharing of discoveries, helping each other access hard-to-find wines,” he says, that follows as a matter of course. “We hook our customers up with new wines.”

Says Peter Neptune, an Orange County wine distributor with Henry Wine Group who earned his master sommelier certificate in 2005, “Having master sommeliers here raises the bar, brings everyone up a notch by increasing the professionalism and encouraging everyone to improve their wine programs.” Neptune is the first master sommelier in decades to earn that credential while working in Southern California.

Having Neptune and Jordan available as mentors makes it easier for Southern California’s sommeliers to study for the MS exam. And as the community matures, earning the credential may well be the standard career path, says Jay Perrin, wine director at Campanile in L.A. Right now, it’s still a choice.

“Part of me wants the piece of paper; it’s validation. Anyone can call themselves a sommelier, but not everyone is a master sommelier,” Perrin says. “But it’s a huge commitment.”

Water Grill’s Bertone and Cut’s Farner, who each have university degrees, believe it’s important to also earn a wine credential. “The food and wine culture here has become much more serious,” Bertone says. “The sommeliers are trying to build a community together; they’re trying to elevate wine for their guests.”

Actually, Sona’s Mendoza says, “I’m doing it for my mom. It’s a diploma.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.