India says it will ship hydroxychloroquine to U.S. after Trump threatens retaliation

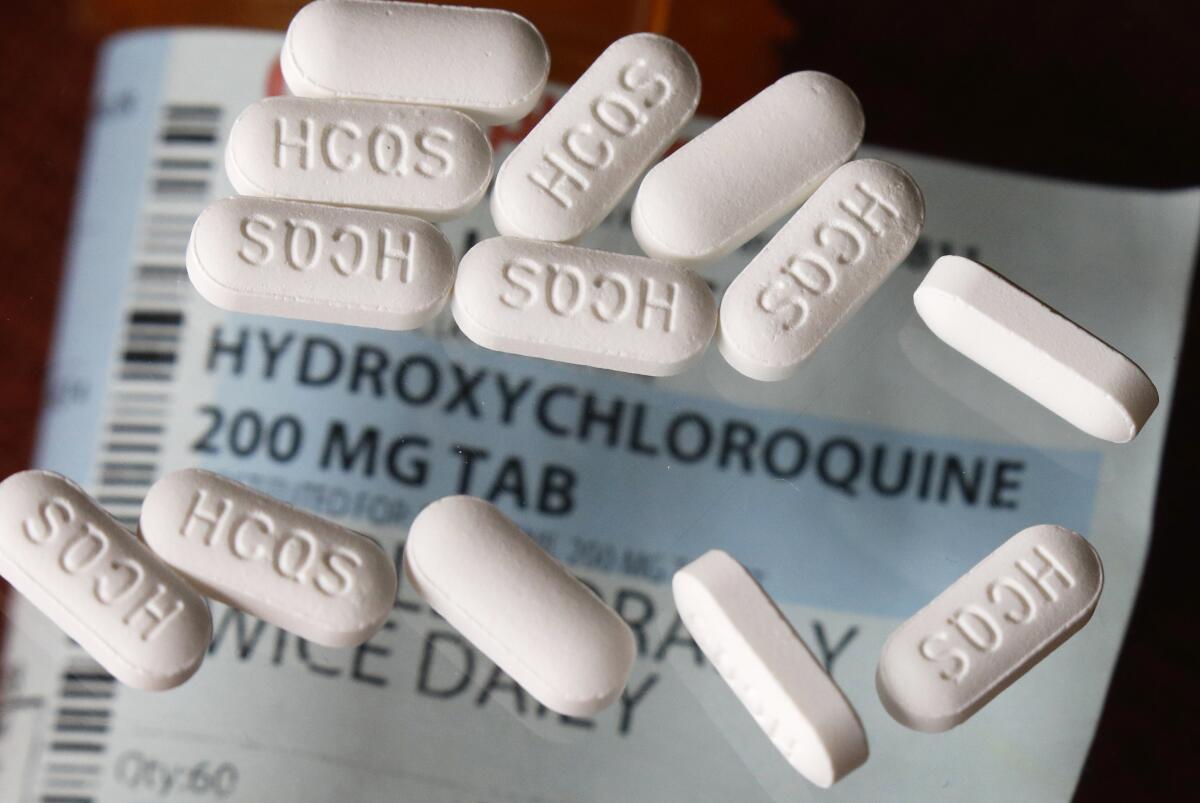

Under pressure from President Trump, the Indian government Tuesday lifted a ban on the export of hydroxychloroquine, paving the way for the anti-malaria drug to be shipped to the U.S. for use against the coronavirus.

The decision came after Trump appealed to Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in a phone call, then told a White House news conference Monday that India could face “retaliation” if it didn’t release the drug.

“I said, ‘We’d appreciate your allowing our supply to come out,’” Trump said of his call with Modi. “If he doesn’t allow it to come out, that would be OK. But of course there may be retaliation. Why wouldn’t there be?”

Trump has aggressively touted hydroxychloroquine as a possible “game changer” in the pandemic despite a lack of conclusive evidence that it works to treat COVID-19, the disease caused by the coronavirus. The U.S. gets nearly half its supply of the drug from India.

India’s foreign affairs ministry said restrictions against the export of hydroxychloroquine and several other drugs were “largely lifted” after the government had ensured there were sufficient supplies to meet domestic need.

New Delhi had stopped exports just days earlier amid a global rush to stockpile the drug, which was developed nearly a century ago to battle malaria and is also used to treat autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis and lupus.

The prospect that malaria drugs will become go-to medications to treat COVID-19 before they’ve been rigorously tested is prompting safety warnings.

Hydroxychloroquine, which is already being used by doctors in the U.S. and other countries to treat the coronavirus, has sharply divided Trump’s pandemic task force.

White House trade advisor Peter Navarro has championed the drug, which has been shown in limited studies in France and China to reduce some symptoms of COVID-19. But Dr. Anthony Fauci, head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, has pushed back against those claims, saying the drug has not been subjected to rigorous clinical trials.

The drug can also have severe side effects, including heart damage.

Still, as Trump tries to show that the U.S. is turning the tide against a virus that has sickened more than 360,000 Americans — by far the most in the world — the Food and Drug Administration last week authorized the experimental use of hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 patients.

Trump has often accused India of unfair trade practices, but he enjoys a warm relationship with Modi, who threw a giant stadium rally for the president when he visited India in February.

Modi’s decision divided India, which is grappling with its own widening coronavirus epidemic. With nearly 5,000 Indians having tested positive for the virus despite one of the lowest rates of testing in the world, the outbreak is threatening to crush India’s overstretched healthcare system.

“We should ramp up production and build our national stockpile before we start exporting,” said K.M. Gopakumar, legal advisor to the Third World Network, a nonprofit think tank that focuses on the pharmaceutical industry. “My concern is that, in a couple of months, when the pandemic surges in African nations, will India be able to send them drugs as well? America is not the only country depending on us.”

Ashok Madan, executive director of the Indian Drug Manufacturers Assn., praised Modi’s decision on humanitarian grounds.

India’s giant generic drug industry was committed “to being the pharmacy of the world,” Madan said. “We are nowhere withering from our responsibilities.”

The race to secure drugs amid the pandemic has seemingly skated over regulatory problems in India’s $37-billion pharmaceutical industry.

Ipca, one of the leading producers of hydroxychloroquine, was banned from exporting products from three facilities to the U.S. in 2015 after FDA inspectors found the Indian company was manipulating raw data and test results to meet quality-control checks.

But last month the company told Indian regulators that the FDA had lifted the ban because of the growing demand for hydroxychloroquine.

Some in India also worry about a double standard in the U.S. drug market.

One of the most promising treatments for COVID-19, an antiviral drug called remdesivir, which was originally developed to fight Ebola, is made by the U.S. pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences. Last month, the FDA designated remdesivir an “orphan drug,” potentially limiting its availability — a decision that sparked such a fierce backlash that it was rescinded two days later.

“Countries should work together, especially at a time of crisis,” Gopakumar said. “So a good question worth asking right now is, will [the] U.S. government give us remdesevir when the time comes?”

Times staff writer Bengali reported from Singapore and special correspondent Krishnan from Goa, India.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.