‘Defiant Requiem’: Nazi prisoners found humanity in music. This concert keeps the message alive

Among the estimated 140,000 Jews who passed through the Nazi ghetto and concentration camp in the Czech town of Terezin was conductor and composer Rafael Schachter, founder of the Prague Chamber Opera.

After Schachter was arrested in 1941 and sent to Terezin, about 30 miles north of Prague, he smuggled in one copy of Verdi’s Requiem, an 1874 composition for Catholic funerals. He taught it to a chorus of 150 — artists, scholars and others who staged concerts of opera, contemporary music and chamber music at Terezin. There even was a small jazz band called the Ghetto Swingers.

Schachter’s singers, accompanied by a pianist, went on to perform Verdi’s Requiem 16 times. The chrous shrank over the years, as members were sent to death camps. By the time they were forced to perform in 1944 as the agitprop of SS officials hosting a delegation from the International Red Cross, Schachter’s group had only 60 members.

The prisoners at Terezin were “starving, ill, living in terror, freezing,” and yet they mustered the energy to gather in a basement and rehearse because “they wanted to learn,” said conductor Murry Sidlin, creator of the concert “Defiant Requiem: Verdi at Terezin.”

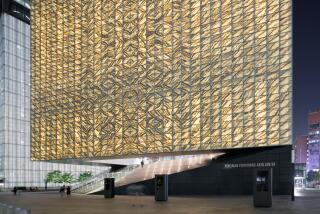

The program combines a choral performance of Verdi’s Requiem with video testimony from surviving members of the Terezin chorus, clips from a rare propaganda film shot by Germans in Terezin and a live performer portraying Schachter. “Defiant Requiem” has its Los Angeles and Orange County premieres with Sidlin conducting the Pacific Symphony and Pacific Chorale and Tony Award winner John Rubinstein (“Pippin”) playing Schachter; performances are Tuesday at Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall in Costa Mesa and April 17 at Royce Hall at UCLA. The latter is presented by the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust and the Defiant Requiem Foundation, the Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit Sidlin founded in 2008.

Paul Nussbaum, president of the Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust, is the son of two Holocaust survivors. His mother was at Terezin in 1944. He said the “Defiant Requiem” is “one of the most poignant examples of spiritual and cultural resistance from the Holocaust.”

With the rise of hate crimes against Jews and Muslims, including the killing of dozens in New Zealand last month and 11 people in a Pittsburgh synagogue last October, “there’s an imperative for all of us to do a better job educating about the Holocaust,” Nussbaum said.

Just last month, two swastikas were scrawled in blood by the restroom at Pan Pacific Park, near the Holocaust museum. Anti-Semitic flyers appeared at Newport Harbor High School not long after photos surfaced of students at a party giving a Nazi salute over red cups arranged in a swastika.

“It’s a rather critical time to expose anti-Semitism historically and make connections with how little it takes for things like this to rise again,” Sidlin said. “We try our best to talk to audiences who come into the hall and tell them what happened not terribly long ago.”

He said, ‘OK, this is hell and I am going to try to make it a little bit less like hell for as long as I can.

— Actor John Rubinstein, who will portray Rafael Schachter in “Defiant Requiem”

Since its premiere in 2002 with the Oregon Symphony in Portland, Sidlin has performed “Defiant Requiem” about 50 times. The concert led to an acclaimed 2012 documentary.

Verdi’s Requiem provided “a harmonious experience” for the singers of Terezin, Sidlin said — a chance to find harmony among fellow humans when it was otherwise impossible. “To organize into something where they are a valuable member of the human mosaic, singing great music and responding to the worst of mankind with the best of mankind,” Sidlin said. “It was nutrition. Maybe they didn’t have anything to eat that was nutritious, but this was their nutrition.”

If you examine the text of the Requiem from a prisoner’s point of view, Sidlin said, certain things take on a different meaning. As an example, he cited the line: “Whatever is hidden shall become evident and nothing shall remain unavenged.”

Schachter loved to look at the Requiem and admire the counterpoint and the brilliance of Verdi, Sidlin said. But once he got to Terezin, “what motivated him, I think, was ‘nothing shall remain unavenged.’ ”

One of the Holocaust survivors who performed in the chorus told Sidlin that Schachter would repeat during rehearsal: “What we are doing now, what we do now is a rehearsal for when we sing in Prague in a beautiful concert hall with a grand symphony orchestra in freedom.”

“Those of us who were born after those days, it’s terribly hard to put yourself in that situation,” said Rubinstein, son of the pianist Arthur Rubinstein, a Polish-born Jew who left his country with Polish ballerina Nela Mlynarska in 1939.

“What would you do? Would you just give up? Just give up and scream and yell and cry and kick the walls until they killed you, or would you see what you could do with your last days on earth?” Rubinstein said, contemplating Schachter’s courage. “He said, ‘OK, this is hell and I am going to try to make it a little bit less like hell for as long as I can and for as many other people as I can.’ ”

After his final performance of Verdi’s Requiem in 1944, Schachter was sent to Auschwitz and later three other camps, where he worked as a laborer. “He died on a death march,” Sidlin said. Schachter was 39.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

‘Defiant Requiem’

When: 8 p.m. Tuesday at Renée and Henry Segerstrom Concert Hall, 615 Town Center Drive, Costa Mesa; 8 p.m. April 17 at UCLA’s Royce Hall, 10745 Dickson Court, Los Angeles

Tickets: $25-$213 (Segerstrom) and $45-$133 (Royce Hall), subject to change

Info: defiantrequiem.org, pacificsymphony.org, lamoth.org

Support our coverage of local arts by becoming a digital subscriber.

See all of our latest arts news and reviews at latimes.com/arts.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.