Rebirth of Jackson Pollock’s ‘Mural’

Myths die hard. Especially creation myths. Messing with the symbolic origins of a world isn’t something to be undertaken lightly.

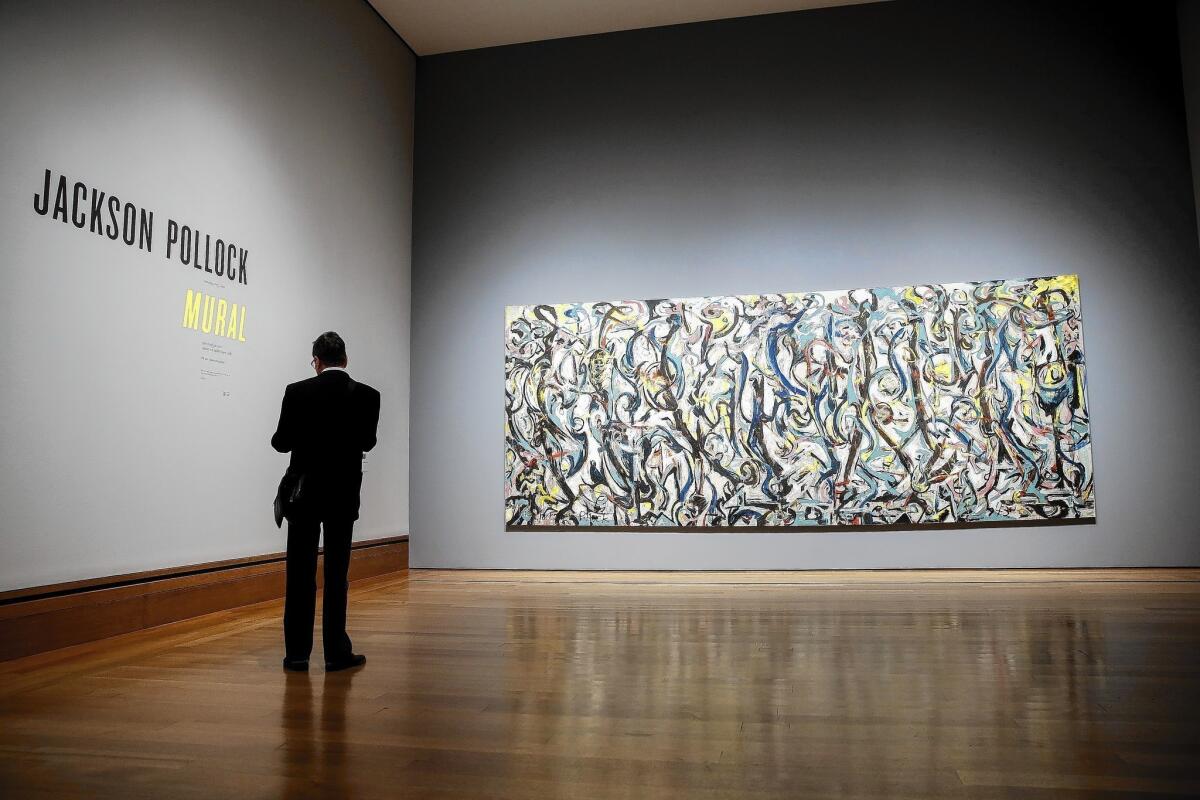

Jackson Pollock’s mammoth 1943 painting “Mural” — nearly 8 feet high, 20 feet wide and covered edge-to-edge with rhythmic, Matisse-like linear arabesques, muscular abstract shapes and piercing voids, all of which he likened to a frenzied mustang stampede — was something entirely new for American art. The great painting represents an early, galvanizing leap toward the emergence of the New York School of Abstract Expressionist art in the aftermath of World War II.

The pivotal painting, owned by the University of Iowa’s Museum of Art, goes on public view at the J. Paul Getty Museum on Tuesday — minus a chunk of its myth. It has been undone by science.

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures by The Times

For the last 21 months, “Mural” underwent much-needed conservation in a project led by the museum and the Getty Conservation Institute. The intensive study is laid out in a fascinating, clearly explained exhibition.

With one caveat, which I’ll get to in a moment, the result is magnificent. Thanks to the Getty’s superlative ministrations, we can see “Mural” in as close an approximation as to what it looked like when Pollock put down his brush 70 years ago.

And — no small thing — the landmark painting has now been re-dated.

That’s largely because one key element in the New York School creation myth is now officially dead. Despite claims made and repeated for decades, Pollock did not paint the epic canvas in one great, glorious burst of nonstop creative fervor.

Instead, a painting revered as a turning point, both for the artist and the history of Modern American art, evolved over many days and perhaps even several weeks.

The usual story is that Pollock fretted over the huge blank canvas for months, unsure of what to do. It sat untouched in his studio, almost as a daily taunt. Then, in a sudden and dramatic binge of brilliant, all-night action, the roiling masterpiece issued forth.

CRITICS’ PICKS: What to watch, where to go, what to eat

Except, apparently not.

Collector and art dealer Peggy Guggenheim commissioned the mural in the summer of 1943 for the entry hall of her East 61st Street Manhattan town house. She was planning a November Pollock show for her gallery, “Art of This Century,” and the mural would be an epic statement of her faith in a mercurial, barely known talent.

The canvas is four times bigger than any Pollock had previously attempted. Notoriously insecure and impulsive, he no doubt struggled.

Just after nightfall on the day before the work was due, Pollock is said to have begun to paint. By 9 a.m. the next morning, 15 tumultuous hours later, “Mural” was done.

“I had a vision,” he later explained. Painter Lee Krasner, the live-in girlfriend who would become his wife, was ecstatic.

“As soon as the paint was dry to the touch, Jackson broke down the stretcher, rolled the canvas, and transported both to Peggy’s apartment building,” Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith wrote in “Jackson Pollock: An American Saga,” their controversial, Pulitzer Prize-winning 1990 biography. It was a version of a story widely reported by Krasner, Guggenheim, critic Clement Greenberg and others.

ART: Can you guess the high price?

Scholarly literature repeats it — although a speculative crack in the edifice appeared in a catalog footnote for the great 1998 Pollock retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. Now, thanks to the careful pigment and other analyses of the GCI’s Tom Learner and Alan Phenix and the museum’s Yvonne Szafran and Laura Rivers, we know for certain that the story isn’t quite right.

The concise, two-room show was organized by Learner, Szafran and Getty curator emeritus Scott Schaefer. With its small but highly detailed book, it shows that Pollock did lay out an initial overall composition, painting wet-on-wet in diluted, high-quality oils of teal, lemon yellow, red and umber. (No sketches are known.) Perhaps that was done in a single lengthy session.

However, much of the paint was applied later. Separate layers each required drying time, some for many days.

MoMA’s retrospective 16 years ago set the painting’s date at December 1943-January 1944. The Getty paint study, coupled with other research, convincingly pushes that back to July-November 1943.

More than 25 paints have been identified. That includes white patches of ordinary house paint — a surprise — which visually open up internal pictorial space in the jampacked image.

PHOTOS: Christopher Knight’s best art moments of 2013

The conservation of “Mural” also included removal of a layer of varnish, applied in 1973 and since yellowed. A dull sheen that unified the surface is gone. The painting is now brighter, livelier and less visually uniform, as if interior shades have been lifted and the sun now shines through. Lost dynamism is restored.

The big painting has also been re-stretched. New, specially constructed stretcher bars conform to a slight sag in the center of the canvas, with a corresponding rise at each bottom corner. The painted image now goes right to the edge all the way around. The sag cannot be physically removed, but the new stretcher visually compensates: The droop appears far less pronounced than before.

And here’s the caveat: The painting is incorrectly installed in the gallery. It’s hung too high on the wall — almost at knee level, when it should be only ankle-high.

The error is significant. Essentially, “Mural” should be a wall, as the artist planned it for Guggenheim’s apartment entry, not a painting on a wall, as the Getty has it.

Pollock also hung it a few inches from the floor for a formal portrait photograph in 1947, when “Mural” was to be first shown at MoMA. The physical relationship between the hectic painting and a viewer should be body to body, not body to eye.

GRAPHIC: Faces to watch 2014 | Entertainment and arts

Installed with its bottom edge at the height of the gallery’s wide baseboards to the right and left, “Mural” is turned into a very large easel painting. Yet the canvas was a big step toward the resolution of what Greenberg, Pollock’s ardent champion, dubbed “the crisis of the easel picture.” Here, resolution denied.

Now that the heroic myth of the fearless, exhausting, one-shot painting binge has been undone, it’s worth asking: What purpose did that improbable myth serve in the first place? And why was it believed?

Fluffing an image of manly vigor surely had something to do with it. Consider Krasner, the tale’s primary source. Pollock was 31 in 1943 — deeply conflicted, an artist in Greenwich Village, not wearing a uniform or serving in a dangerous war abroad like most young American men. (His Jungian analyst, Violet de Laszlo, helped him get a 4-F draft deferment by citing a “certain schizoid disposition.”) Krasner knew the rampant rumors of his closeted or repressed homosexuality. The heroic myth of one brilliant, all-night painting campaign propped up an image of virility.

Greenberg, an ambitious young critic, was also looking for a painter who could be torch-bearer for a distinctly American Modernism. He needed a native art as profound as that produced in Europe, but one stylistically free of precedents from the art of a continent going up in smoke.

Pollock had been plumbing the Jungian collective unconscious in works like “She-Wolf,” “Guardians of the Secret” and “The Moon-Woman Cuts the Circle.” The near-total abstraction of “Mural” abandoned that, as it did the figurative American jingoism of his mentor, Thomas Hart Benton — Modernism’s arch-enemy. And its inventive robustness owed far more to Mexican muralists like David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco than to effete European Surrealism.

PHOTOS: The most fascinating arts stories of 2013

Think, if you will, of Pollock as the blustering Gen. Patton or MacArthur of America’s painting troops, leading the unstoppable charge to victory. “I took one look at [‘Mural’],” Greenberg later claimed, “and I knew Jackson was the greatest painter this country had produced.” He would be heroic standard-bearer for art’s Greatest Generation.

Which begs a question: Does the demolition of a central tenet of the New York School’s creation myth lessen “Mural’s” critical importance — or Pollock’s?

I’d say just the opposite.

For despite Pollock’s well-documented psychological problems, the rigorously constructed painting shows an artist who knew what he was about. Over days (or weeks), he honed his own steadily maturing aesthetic. And he was on an exploratory track that, a few years hence, would produce the magnificent drip-paintings on which his enduring reputation rests.

As a bonus, the myth-busting smashes today’s popular fantasy of artist-as-volcanic-genius, with masterpieces flowing like lava out of gushing fingertips. Pollock was, instead, an actual artist. He labored on “Mural,” and he labored hard.

christopher.knight@latimes.com

-------------------------------------

Jackson Pollock’s ‘Mural’

Where: J. Paul Getty Museum, 1200 Getty Center Drive, Brentwood

When: Opens Tuesday, up through June 1. Closed Mondays.

Information: (310) 440-7300, https://www.getty.edu

MORE

PHOTOS: Hollywood stars on stage

PHOTOS: Arts and culture in pictures

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.