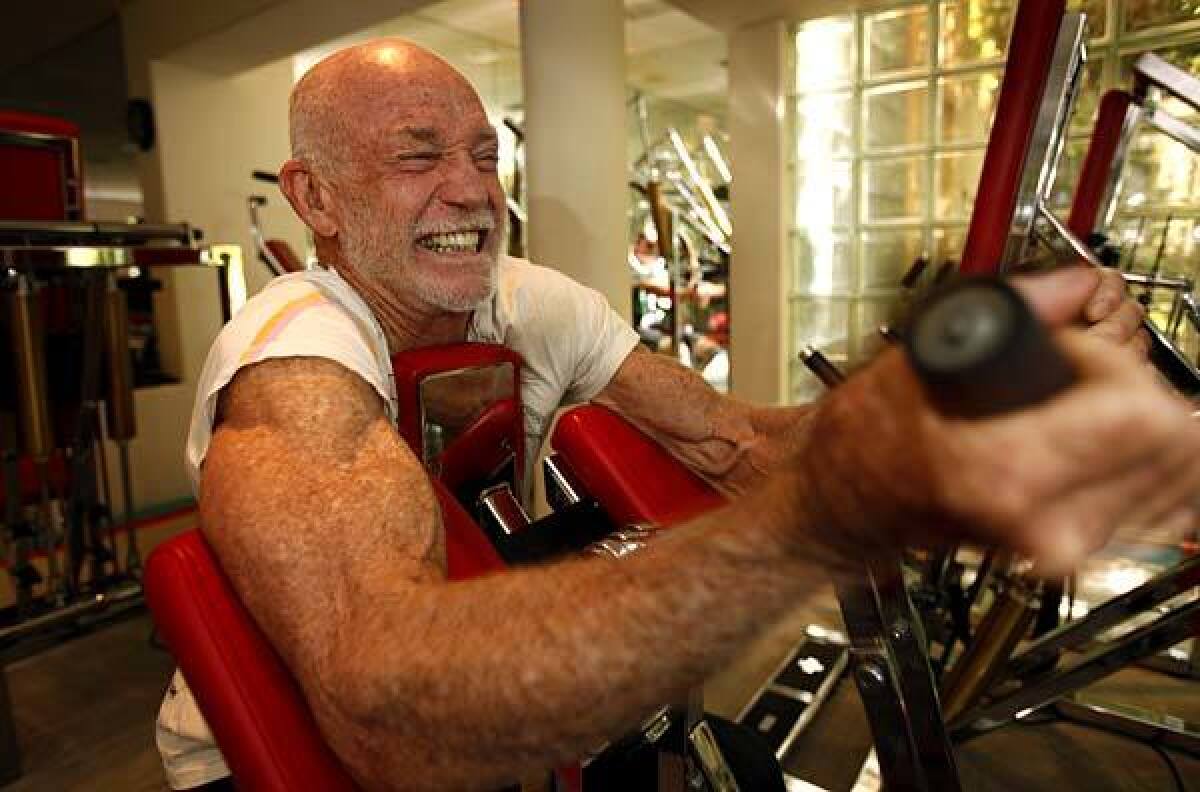

It’s hard work being Mr. Lucky

Nearly six decades ago, a 6-foot-2, rail-thin 17-year-old from Burbank High muffed the kickoff in the last football game of the season. “I kicked the ball about 15 yards -- then ran over and dove on it. Coach yelled out, ‘Great onside kick, Wildman.’

“A teammate looked at me and said, ‘Don, you’re the only guy who can fall on an outhouse and come up smelling like a rose.’ They called it ‘the Wildman luck.’ ”

As the fighting, trouble-making, evolution-believing son of Pentecostal preacher Al Wildman, an acolyte of famed evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, Don Wildman always managed to make the best of a bad situation -- even when he was shipped out to the Korean War before graduation to “get me on the right track.”

His first day in Korea, Wildman found himself a medic in a wiped-out convoy surrounded by dozens of dead American boys and thousands of Red Chinese soldiers pouring south across the border.

“I high-tailed it across a frozen river, certain I was going to die,” he said. ‘I wanted to shoot myself in the foot, break my hand, anything to go home. Then I met other survivors. If they could take it, I could too.

“When I got home, I had a reference point for the rest of my life. Nothing was as bad as Korea. If it wasn’t life or death, I could deal with it.”

Back in L.A. in 1953, Wildman worked construction, sold insurance, got married and, to put some brawn on his skinny frame, began working out at a Vic Tanny gym in Burbank. He ended up running the gym for 10 years, battling the stereotypes that claimed fitness was dangerous for women and that men with muscles were dumb -- even as he built up his own bulk.

“I tried to lead by example,” he said. “Unlike these MBAs who never worked out, I had to look the part. When I started out, it was a selling business -- and a muscle-head who totally believed was a better salesman. I guess because my father was a minister, I naturally ended up doing the same thing: changing lives.”

Wildman began preaching the fitness gospel to a much larger audience when Tanny went bankrupt in 1962. “It was the Wildman luck again -- I was in the right place at the right time,” he says.

Creditors contacted him about taking over eight clubs in Chicago. Soon he was buying big and small chains in other cities, always careful to maintain their separate identities to avoid the system-wide scandals that plagued the fitness business. Driving traffic with ads featuring celebrities such as Raquel Welch, he rode the fitness and racquetball wave to ownership of 17 chains nationwide under the umbrella of his Health and Tennis Corp. By 1993, when he retired from running Bally’s, the company that had bought him out a decade before, there were 400 clubs, the most in the country.

All the while, Wildman kept working out. His time crunch, and the advent of multi-station weight machines in the ‘60s and ‘70s, led him to clear messy barbells off the floor and experiment with what became known as “circuit training,” rapidly moving from one exercise to another.

“I think I invented circuit training because I had to -- I didn’t have the time to rest. You work one muscle group, then the opposing group -- and you’re done in half the time.” Circuit training was a huge hit -- especially with women, who flooded into his clubs. Training at 6 a.m. every day, Wildman built up to 237 pounds at age 37, leaving him time to pursue his big hobby, sailboat racing.

In 1982, the morning after Wildman and his crew of 20 became the first to win all three of the Chicago Yacht Club’s famous Mackinac races in one season, a Fortune magazine writer asked him what was next. Drunk on champagne, Wildman remembered something about a new sport he’d recently seen on TV, and blurted, “I might do that Ironman.”

“That ended up in the article,” he said. “Now, I had to do it.”

So he did. Nine times.

--

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.