Flirting With Disaster

Like pressure building invisibly along an earthquake fault, a crisis is mounting for homeowners who won’t have enough insurance to cover their losses in a fire, earthquake or other catastrophe.

Major insurance companies have quietly slashed their policyholders’ coverage in recent years, raising deductibles, lowering caps and, perhaps most important, doing away with guaranteed-replacement coverage that promised to rebuild a damaged home regardless of the cost.

At the same time, earthquake insurance has been so radically constricted that today’s typical policy offers tens of thousands of dollars less coverage than what was available before the Northridge earthquake.

It’s a one-two punch that insurance companies say they needed to take to fend off huge risks that could bankrupt them.

But consumer advocates and some analysts of the insurance industry say the changes could deliver a knockout blow to homeowners’ finances, exposing millions of people to the possibility of devastating losses. Because of the high propensity for natural disasters here, California homeowners are more likely to find themselves on the ropes.

“People don’t realize what has been happening,” said Brian Sullivan, editor of Property Insurance Report, a newsletter published in Laguna Niguel that tracks insurance industry trends nationwide. “Consumers have to be savvy about the changes that are happening and recognize that their policy isn’t what it used to be.”

Not surprisingly, insurance companies and their critics disagree about the magnitude of the potential problem.

A State Farm survey of its customers completed in 1996 found that 30% to 35% had less insurance than the company thought they needed. State Farm says it has worked diligently to boost those customers’ coverage.

The Western Insurance Information Service, a Los Angeles-based industry trade group, says it can’t quantify how many people are underinsured but that insurers are concerned enough about the problem and its legal and financial implications to support education and outreach programs.

“Absolutely there has been a problem, and the insurers acknowledge that,” said spokeswoman Candysse Miller. “That’s why we try and do promotions that help people understand what it means to be properly insured and how important that is.”

Industry critics say the percentage of underinsured policyholders is closer to 65%--possibly as high as 85%--among the nation’s 60 million homeowners. A recent study by Marshall & Swift, a Los Angeles building-cost consultant, estimates that at least 70% of residences nationwide are underinsured by an average of 35%. The company estimated the insurers could be collecting $4.5 billion a year in additional premiums--meaning homeowners could be underinsured by tens of billions of dollars.

“Homeowners are at enormous risk,” said Greg Kaighn, a Sacramento attorney who represents homeowners against insurance companies. “Insurance companies have taken [the risk] and dumped it all back on the consumer.”

Many say the extent of the problem won’t be known until the next major disaster, when policyholders try to make claims and discover they don’t have enough insurance.

Insurers and their opponents agree that the current situation arose from the collision of two trends: a gradual expansion in what insurance companies offered their customers, and an increase in the frequency of major disasters, in California and nationwide.

For years, homeowners insurance was hugely profitable, thanks to benign weather patterns that stretched from the 1960s to the early 1980s. Emboldened by their profits and eager for more business, insurers kept increasing the coverage limits on their policies, lowering deductibles and adding features such as guaranteed-replacement cost, which promised customers their homes would be rebuilt regardless of how much underlying insurance they had bought.

At the same time, consumers figured out that homeowners insurance “could be used not just for disasters, but if you dropped your camera on the garage floor,” industry analyst Sullivan said. That also led to more claims and more exposure to risk.

“They were giving away too much insurance,” Sullivan said. “It became an all-risk policy that covered everything, and that’s bad business.”

Furthermore, competition induced some agents to calculate low replacement values on homes so they could quote lower premiums and win more business, analysts said. For example, an agent might insure a $300,000 home for only $200,000 in order to lower the premium, then tell the homeowner the guaranteed-replacement clause would pick up the difference. So if the home burned down, the homeowner would indeed get a check for $300,000.

“A lot of times formulas [for replacement values] were winked at in the old times,” Sullivan said. “You don’t often have to replace a whole house, so what was the risk? Well, surprise.”

Since 1989, the industry has been rocked by the 10 largest disasters in insurance history, including Hurricanes Andrew, Hugo and Opal; the Loma Prieta earthquake; massive winter storms in 1993; and the Northridge quake in 1994.

Insurers say the $12.5 billion in insured damages from Northridge alone cost them more in claims than they had ever collected in earthquake premiums.

A fear of future losses led most insurers to stop writing earthquake policies in California until the Legislature created the California Earthquake Authority in 1996 to assume most of the risk.

Most major insurance companies now send their customers to the authority for earthquake coverage. But these policies have higher deductibles and sharply lower coverage limits than what insurance companies offered before the quake. Often, they are much more costly as well.

In 1994, Len and Barbara Vosen of Northridge paid $560 for an earthquake policy that covered most of the $140,000 damage to their home and $60,000 in destroyed furnishings. Today they pay more than $1,800 for a policy that has a 50% higher deductible and provides only $5,000 of “contents coverage” that would replace lost furnishings. Their pool, patio and fences are no longer covered, and the cost of living away from home while damage is fixed--known as “loss of use” coverage--is limited to $1,500, an amount the Vosens say would barely cover a month’s rent.

Homeowners can get a lower deductible, more contents and “loss of use” by paying a higher premium. But most people who have the insurance stick to the bare-bones coverage.

And its coverage is so much lower that, had the current quake insurance conditions been in force in 1994, few Northridge victims would have been able to collect much if anything. For most victims, the 15% deductible would have precluded any claim, Sullivan said.

Even before insurers advocated the creation of the earthquake pool, however, they were starting to limit their coverage.

State Farm was eliminating guaranteed-replacement coverage and capping payouts on some of its earthquake policies as early as 1985. The decision was costly. In June, plaintiffs’ attorneys revealed that the company had paid $100 million to settle claims from 117 policyholders who said they hadn’t been given adequate notice of the change.

The state now requires that all homeowners receive a clear notice of what their policy covers when the policy is renewed. Whether homeowners read the disclosure or understand what it says is another matter.

“Who wants to read their insurance policy on a Saturday night?” the trade group’s Miller asked. “It’s hard to get people to read their policies.”

The trend toward capped payouts continued apace. State Farm, Allstate and Farmers, which together write more than 50% of homeowners policies in California and 40% nationwide, gradually eliminated guaranteed-replacement coverage on homeowners insurance starting in 1992. Many smaller insurers followed suit or added other kinds of restrictions to their coverage.

Instead of guaranteed replacement, Miller said, insurers have instituted policies that limit their payout to 120% or 150% of a home’s insured cost.

The difference in coverage can be huge.

Say a home would cost $250,000 to rebuild but that the homeowner has failed to update the insurance after a remodeling or simply failed to get the right amount of insurance in the first place, and so is 35% underinsured, with coverage of just $162,500.

Under a guaranteed-replacement policy, the insurer would have paid $250,000. But with a 120% cap, the homeowner would get $195,000 from the insurer. The rest--$55,000 in this example--would come out of the homeowner’s pocket.

Insurers vary dramatically in how they have handled the switch from guaranteed-replacement coverage to coverage with caps.

State Farm, which writes nearly a quarter of the California homeowners business and which caps replacement costs at 120% of insured value, says it reviewed every one of its 6.3 million policies nationwide, sending agents or other company representatives to personally inspect each property and make sure customers had adequate insurance.

Coverage limits were compared with building costs for each area, and polices were adjusted accordingly, said spokesman Bill Sirola. These new policies also come with built-in inflation riders that are supposed to adjust a homeowner’s coverage to keep up with rising building costs, and an additional 10% coverage to pay for bringing older homes up to modern building codes, Sirola said.

Farmers, on the other hand, simply sent notices to its homeowners about the change to a 125% cap and is conducting spot reviews to determine how many homeowners may be underinsured.

“The consumer has the responsibility to determine what their coverage should be,” said Farmers spokeswoman Diane Tasaka. “We can make some estimate about what the replacement cost should be, but if the consumer doesn’t tell us about remodeling, about upgrades, about special features that could increase the house’s worth, there’s no way we’re going to know.”

Industry analyst Sullivan said he believes the insurance companies’ reviews ensure that most homeowners will have adequate coverage. Those most at risk are people with older or unusual homes that may not fit neatly into insurance company formulas, or people who have remodeled their homes and failed to notify their insurers, he said.

But some consumer advocates question the diligence of insurance company reviews and the accuracy of the calculations. Competitive pressures may still be inducing agents to quote too-low replacement values--but now the stakes are higher, because guaranteed-replacement coverage will no longer pick up the difference, the advocates say.

“Some companies are careful and others are sloppy, which puts people at risk,” said Bill Ahern, an insurance expert and onetime consumer advocate with San Francisco-based Consumers Union.

In addition, coverage designed to pay to rebuild homes to current building codes may be inadequate for homes that are more than 30 years old or that were built in areas that have since radically modified their building codes.

The situation is especially perilous for customers who rarely review their coverage or who don’t compare their agents’ estimates with information from independent sources, such as home appraisers, said Ina De Long, a former State Farm claims agent and supervisor-turned-consumer advocate. Each year they are underinsured, the gap widens between what rebuilding would cost and what their insurance companies would pay.

“The policyholder is placed in the position that the longer they trust the company, the worse position they’re going to be in,” De Long said.

Bert and Pepper Tibbet of Pasadena have firsthand knowledge of what happens when a home is underinsured. The couple say State Farm and the California FAIR plan, an industry-supported pool that covers high-risk properties, in 1992 calculated the cost to rebuild the Tibbets’ home at $204,000. One year later, the 1993 Altadena wildfires burned their home of 25 years to the ground. Contractors estimated the home would cost more than $400,000 to replace, but the FAIR plan refused to pay the difference.

In addition, the Tibbets discovered that any claims they made for money spent on living expenses while their home was being rebuilt would be deducted from their insurance proceeds. They say they were also denied a chance to buy building-code-upgrade coverage, which would have helped them rebuild their home to current safety standards.

“That [building code upgrade] alone would have given us another $30,000,” said Bert Tibbet.

Since the fire, the Tibbets have lived a nomadic existence, staying in friends’ guest houses and borrowed motor homes while they continue to pay the mortgage on their now-razed home. The couple has sued State Farm and the FAIR plan, claiming fraud, misrepresentation and unfair competition.

The threat of future lawsuits from underinsured homeowners also worries the insurance agents who help determine how much insurance customers buy. Although many companies say proper coverage is the consumer’s responsibility, some court decisions have held that the onus was on the agent to determine adequate insurance.

“It’s definitely a concern,” said Jim Armitage, a South Pasadena insurance broker and spokesman for the Independent Brokers and Agents of the West. “We would be at risk [from lawsuits]. That’s why we have errors-and-omissions insurance.”

Although the homeowners insurance market has returned to profitability, industry experts do not expect insurers to begin expanding coverage or lowering premiums significantly any time soon.

“Right now we’re in the very beginning stages” of increased competition, Miller said. Insurers are still leery of potential losses and unwilling to increase their risk, she said.

That means it is more critical than ever for consumers to review their policies and make sure they are adequately covered, experts said. Homeowners should ask their agents to review their coverage at least once a year and after any remodeling or other improvements, Sullivan said. Consumers can also hire a home appraiser for $150 to $300 to conduct an independent review.

“It’s always smart to be responsible for your own needs and to study your own contract,” he said. “It’s your financial well-being, and no one is going to care about that more than you.”

Only 17% of California’s homeowners have earthquake insurance. Are the rest in denial--or making a rational choice?

Some financial planners suggest the latter. They say that the majority of California homeowners are opting out after weighing the relatively remote chance of a temblor destroying their homes against the high cost of today’s earthquake coverage.

But we don’t buy insurance coverage just to protect us from likely occurrences. We get insurance to guard against unlikely and financially devastating events.

That’s why we buy life insurance: Most of us don’t expect our families to need it. Not having coverage, however, could mean a financial nightmare for our families if the unlikely should happen and a breadwinner dies prematurely.

Of course, some people wouldn’t buy, say, auto liability coverage at all if it wasn’t required by law. Some would even forgo homeowners insurance if their mortgage lenders didn’t force them to buy it. Some people are more than willing to roll the dice--but they should be clear about the real stakes.

In the case of quake insurance, people who decided long ago to do without it might want to revisit the issue--especially in light of changes in the last year that have made coverage more appealing.

Earthquake insurance coverage changed radically after the 1994 Northridge temblor.

Until then, companies that wrote homeowners insurance in the state were also required to offer earthquake coverage. After Northridge, most insurers refused to write either, saying the $12.5 billion in insurance claims from the quake was far higher than expected--higher, in fact, than the total of all earthquake insurance premiums ever collected in California.

The state Legislature eventually responded by created the California Earthquake Authority, a state-run insurance pool.

The first policies were bare bones. Instead of 5% or 10% deductibles, the CEA policies required homeowners to pay 15%. That meant that a homeowner insured for $300,000 had to pay the first $45,000 for repairs before coverage kicked in. The policies didn’t cover landscaping, pools or anything else outside the actual home.

Inside the home, earthquake coverage was spartan, covering just $5,000 of contents. Everything else that toppled over, wrenched apart or fell out of cabinets had to be replaced by the homeowner.

Oh, and you probably would have had to move in with relatives; unlike previous earthquake insurance policies, which covered rent and other living expenses for six months to a year while your home was being rebuilt, CEA’s coverage paid just $1,500--which just about covered a month at a Motel 6.

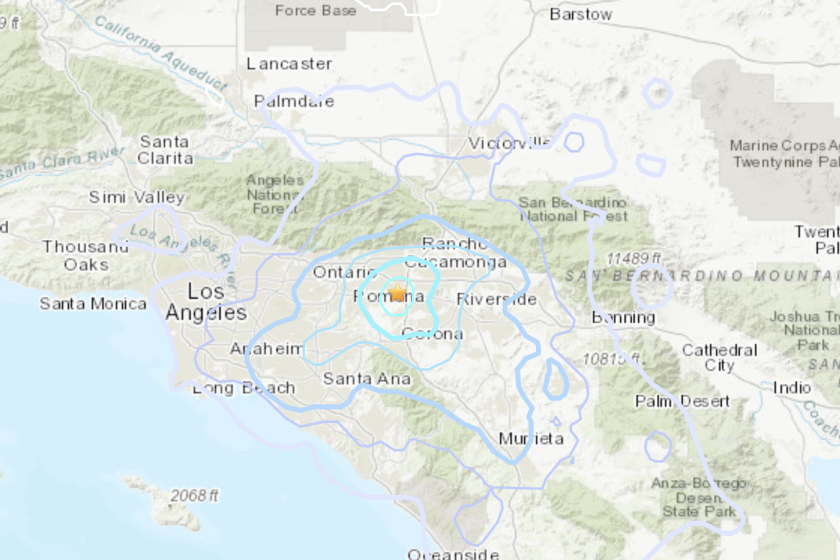

To make matters worse, the coverage was often more expensive--sometimes much more expensive--than the more comprehensive private earthquake policies it replaced. CEA’s enabling legislation required the authority to base its rates on the latest scientific advancements in predicting earth movements, and the scientists discovered that some areas once presumed safe--portions of San Bernardino and Riverside, for example--were actually riskier than previously thought.

But the state finally responded to homeowners’ howls by offering more quake insurance options through CEA, including lower deductibles and greater contents coverage, for somewhat higher premiums.

Two private companies, Pacific Select and GeoVera (now both owned by St. Paul Cos.), also began to offer more comprehensive earthquake policies.

CEA now says demand for its enhanced policies is greater than anticipated: Nearly 34,000 homeowners have purchased the additional coverage in the first year it was been available, compared with 917,000 who have the bare-bones CEA policies.

That still leaves nearly five out of six homeowners with no quake coverage, however.

Some people are wealthy enough to be able to walk away from the financial investment of a home, of course, and others have so little equity at stake that protecting it from earthquake damage may not make much sense.

But if your reasons for not having earthquake insurance include any of the following, you may wish to rethink your stance:

* “My home survived the [fill in the blank] earthquake just fine.” For anyone who knows anything about quakes, this is perhaps the silliest of all rationalizations.

Each earthquake is as individual as a fingerprint, with motion traveling through the ground in unique ways. In addition, new fault lines are being discovered all the time. The earthquake created by the fault under Northridge may not have touched your bungalow, but a shifting fault elsewhere in the Los Angeles area could leave it in splinters.

* “My home is bolted to its foundation”’ This is a better argument than most; some respected earthquake researchers are themselves spending money on earthquake retrofitting rather than paying for insurance coverage.

But even they will admit that no amount of retrofitting can protect against a truly devastating shaker. Bolting seems to work best for one-story wood-frame homes; homes that are two or more stories or have big picture windows or other large gaps in the frames, are likely to suffer more damage even if bolted.

Of course, all the bolting in the world won’t help much if the ground beneath the foundation gives way. In Anchorage, Alaska, a whole neighborhood of homes slipped out to sea when the massive 1964 earthquake liquefied the ground on which they sat.

* “I’ll get FEMA money to rebuild.” Affected homeowners may qualify for low-interest loans offered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency through the Small Business Administration. But these loans are not free money; homeowners are obligated to pay them back, and they are entered in your personal net worth statement as a liability, offsetting an equal amount of assets.

Some observers question how much money will available after the next major earthquake; numerous disasters have soured many in Congress on the idea of handing cash to people who refuse to get insurance.

* “I’ll just hand over the keys to the bank.” Homeowners who let their banks foreclose on earthquake-devastated homes not only lose all their equity, but also put their credit rating at risk. Depending on lenders’ reactions, it may be difficult or impossible to borrow money for another home for several years.

For many of us, our homes represent our largest financial asset. We should think carefully before considering walking away as an option.

Of course, even people who do have insurance will probably suffer some loss of equity in a quake-hit area, at least temporarily. Just ask anyone who tried to sell a home in Northridge in the mid-1990s. A few intrepid souls snapped up these “distressed” properties, reasoning that the chances of another quake hitting the same area were especially remote, but many potential buyers stayed away.

Facing a temporary loss of equity is one thing; it’s quite another to suffer such a huge loss from uninsured quake damage that you’re saddled with a 10- to 30-year rebuilding loan, or that you lose your equity entirely by foreclosure.

Californians have a well-deserved reputation for being in denial. We build our homes on flood plains, on brushy mountainsides, in the path of mudslides and on or near earthquake faults. Most of the time, most of us avoid catastrophe. But we should acknowledge that someday our luck could run out--and consider whether it’s worth taking precautions to protect against the unthinkable.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.