A wealthy developer owns a rare plot of green in a very crowded part of L.A. What does he owe his neighbors?

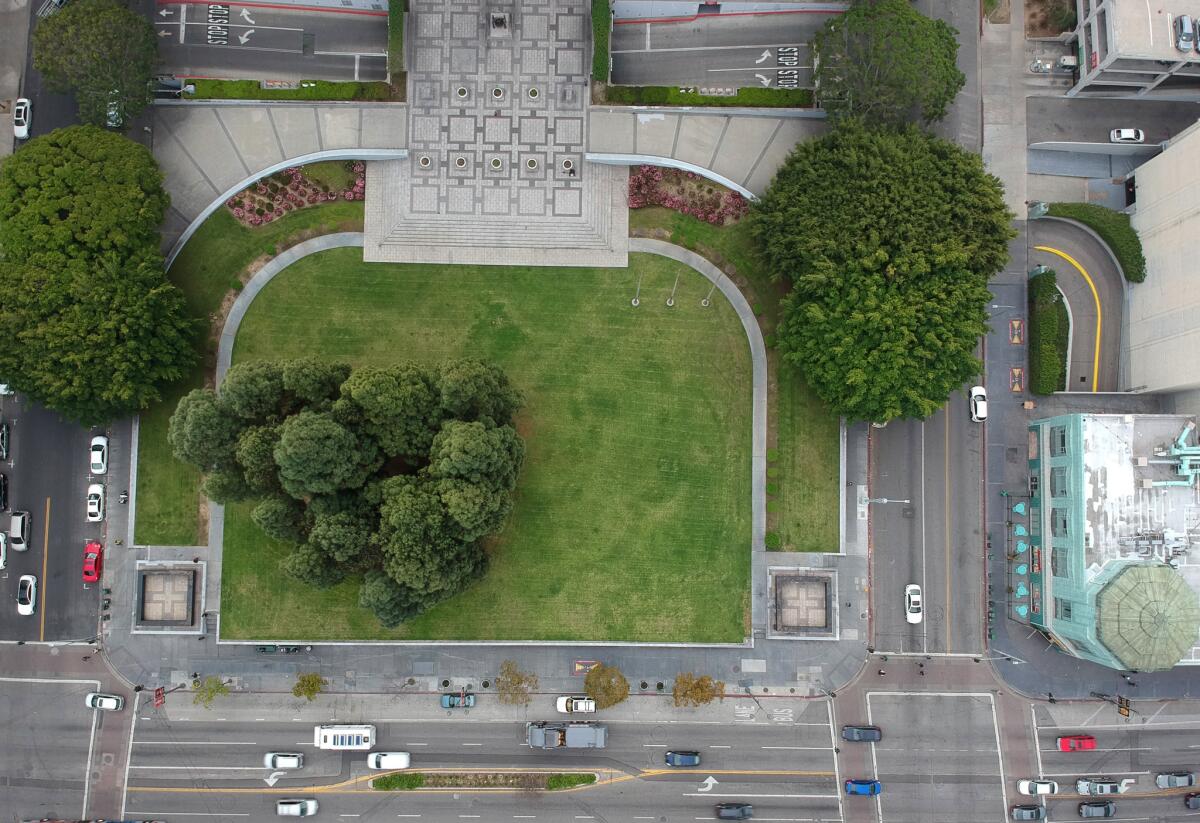

A grassy horseshoe-shaped park an acre wide in the heart of Koreatown takes up some of the hottest real estate in Los Angeles.

Pine trees tower over rocks scattered in the center of the plot, the only green space for miles along Wilshire Boulevard. Residents say it’s a much-needed respite in one of the densest, most park-poor neighborhoods of Los Angeles.

Even if a private security guard will chase you off the minute you set foot on the grass.

The park was created in 1966 by a family building a national headquarters for their insurance company. They built on just half the lot, turning the rest into a landscaped plaza they hoped would serve “to strengthen the central city, to enhance it, to beautify it.”

Half a century later, Liberty Park, as the Mitchell family of Beneficial Insurance Group dubbed it, became a focal point of tensions between the latest building boom spurred by the city’s housing shortage, and Angelenos living in increasing density.

The latest owner of the block, Koreatown developer Jamison Services, wanted to replace the park with a 36-story residential and commercial tower.

A year-long heated skirmish ended last month with the city designating the property a historic-cultural monument, protecting it from immediate development. The controversy over the park brought to a head the perennial question: What, if anything, does a wealthy owner of a private property owe the community and city around it?

With about 500 units and 60,000 square feet of retail space, the planned tower was one of more than a dozen projects in and around Koreatown in the works by the developer, David Lee, an internist turned real estate magnate.

When notices were circulated for the high-rise in late 2016, neighborhood residents became alarmed. The park had long been a gathering place for the community, where friends met up for coffee and hundreds came together for Earth Day events and World Cup viewings.

“It’s a place of rest in the city center, the only grass park in Koreatown,” said Kisuk Jun, 65, who has lived and worked in Koreatown for 35 years. “How stifling would that be, a 36-story building?”

Residents rallied in building lobbies and a nearby Denny’s to create a campaign they called “Save Liberty Park.”

“It’s not every day you figure out how to save a park,” said Anne Kim, one of those spearheading the movement

Recent efforts to create new open space in the area have ended in disappointment. A project for a Koreatown Central Park that had secured $5 million in state funding in 2010 fizzled.

Around the same time, the developer behind a 29-story luxury tower pledged to provide 12,000 square feet of public open space after negotiating with community groups, in exchange for $17.5 million in loans and tax breaks. What the public ultimately got were several small islands of mulch with a smattering of succulents.

To save Liberty Park, Koreatown residents went door to door gathering thousands of signatures. They raised more than $10,000 to commission an architectural study and solicited backing from prominent architects, community organizations and the Los Angeles Conservancy.

They petitioned the city to recognize the plaza and the park as a historic-cultural monument. They pointed out that the plaza reflected the postwar development of the Wilshire Center area and was the work of noted landscape architect Peter Walker, who also designed the 9/11 memorial in lower Manhattan. With the designation, the city’s Cultural Heritage Commission is required to sign off on any changes to the property and has the right to stave off demolition for up to a year.

In February, activists Kim and Annette van Duren met with Lee, the developer, at the offices of City Council President Herb Wesson, whose district includes the park.

Lee grew frustrated during the meeting and told the residents the plot was his private property and he could do with it as he wished, the residents said. He told them he could build a wall around it, pave it and park cars on it and guard it with guns, according to Kim and van Duren, who filed a police report after hearing Lee’s comments.

Lee said the comments were “misunderstood by valued friends, and to those individuals I sincerely apologize.”

At a March hearing before the city’s Planning and Land Use Management Committee, about 20 residents and community activists urged the city to grant the plaza and park historic status. One advocate urged those who know the developer to ask that he allow the public access to the park. A representative for Wesson said he was fully supportive of the designation.

“I see a lot of old-time residents getting shut out of this place and wonder what all this development is for if not for the people who live there,” said Sola Shin, whose family has lived in Koreatown for 40 years. “I think having a public space, trees, parks, that’s one the greatest equalizers of the city, and I think it’s really necessary that we keep it there.”

Katelyn Scanlan, an architect who moved here a year ago, said she met a neighbor at Liberty Park and struck up a conversation about the space.

“What made L.A. home to me was having that interaction and having that public space,” she said. “Preserving places like this can help foster an L.A. for all.”

Following the City Council’s vote March 7, Garrett Lee, president of Jamison Properties and the elder Lee’s son, said the company respected the city’s decision and would preserve the open space. He said the company was proud to be a part of Koreatown and wanted to work with the community “for the betterment of our neighborhood.”

The company did not respond to questions about why it wasn’t allowing people to walk or sit on the grass, or whether it had any plans to do so. In the week the park became a historic monument, a security guard asked a visitor to leave. He said the public wasn’t allowed because of tagging.

Residents involved in the campaign said they were still thrilled, even if they are only able to walk around it and children and pets are shooed off the grass. They said the victory was empowering.

“I think this is just the beginning,” Kim said. “Hopefully developers take notice, city politicians take notice. Now we have a strong voice, and it’s a very united voice.”

For more California news, follow me on Twitter @vicjkim

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.