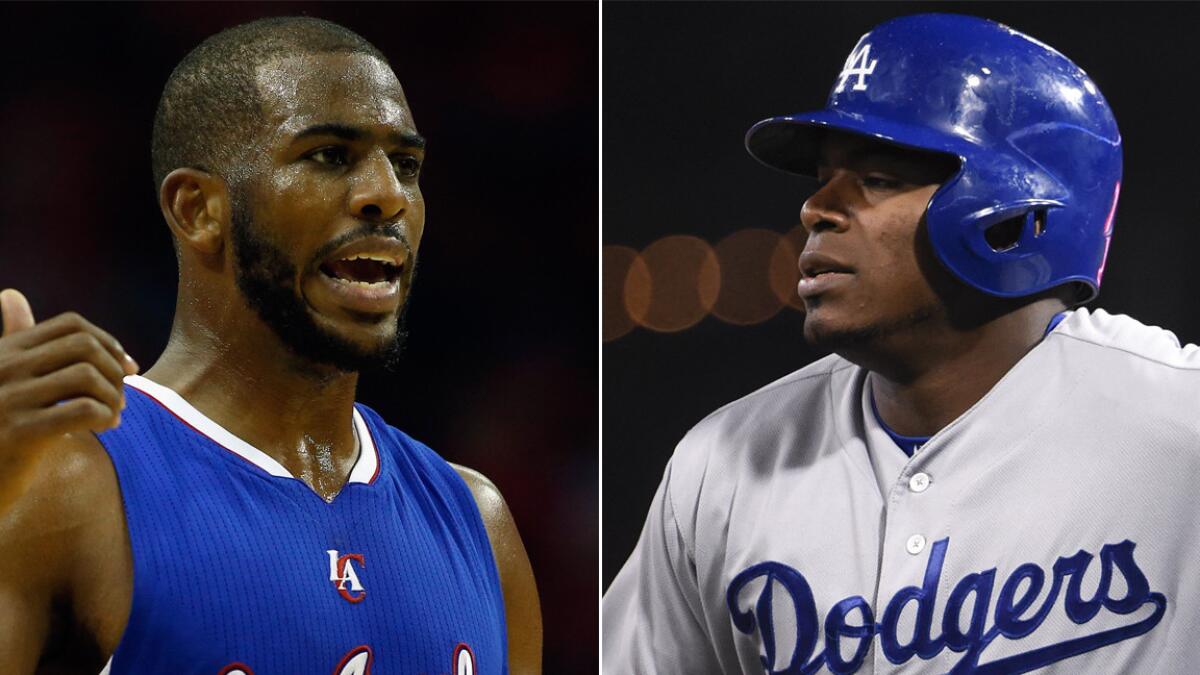

Clippers’ Chris Paul, Dodgers’ Yasiel Puig know agony of the hamstring

Clippers point guard Chris Paul, left, and Dodgers right fielder Yasiel Puig have each battled hamstring injuries in recent weeks.

Clippers point guard Chris Paul knows the back of his leg like the back of his hand.

Hamstring injuries will do that to an athlete. Those insidious ailments, which bring into searing focus a muscle group that’s often ignored, can sideline finely tuned athletes for weeks and sometimes months.

The Dodgers’ Yasiel Puig knows all about that. He’s on the disabled list because of a hamstring injury, and isn’t expected back any time soon.

While Paul gritted his way back onto the court within days of sustaining his injury and has gingerly led the Clippers into Sunday’s Game 7 against Houston in the Western Conference semifinals, Puig is in the throes of hamstring Hades. The All-Star right fielder underwent an MRI examination Monday that confirmed suspicions he again strained his left hamstring while on a minor league rehabilitation assignment over the weekend, prolonging the agony of an injury he first suffered on April 13.

“I’ve seen a lot of guys go right in the tank when they try to come back too early from a hamstring,” said Dr. James Bradley, team physician for the Pittsburgh Steelers and a preeminent authority on hamstring injuries. “It may say ‘Porsche’ on the back of their jersey, but at that point they’re really a Chevy.”

Paul is far from the only NBA player who has missed time in these playoffs because of a hamstring injury. Chicago forward Pau Gasol sat two games in the Eastern Conference semifinals, a series the Bulls lost to Cleveland, and Memphis guard Tony Allen dealt with one, too, missing all of Game 5 and most of Game 6 on Friday, when the Grizzlies were eliminated by Golden State.

A hamstring is a group of muscles that extends down the back of an upper leg, from the ischium, just above the hip joint, to just below the knee. The typical injury occurs when one or more of these muscles is over-stretched, and such injuries can range from a tweak, to a tear, to a hamstring that is torn completely off the bone.

“The athletes you see mostly with hamstring injuries are the ones who are relying a lot on the quick-twitch firing of muscles, like sprinters, point guards in basketball, receivers in football,” said Dr. Luga Podesta, a sports medicine specialist at Kerlan-Jobe Orthopaedic Clinic in Los Angeles.

“You see it in sprinting, but you also see it in basketball when guys come down on it in a certain position, or jump in a certain position, and you see that stretching of the muscle.”

Paradoxically, Paul, who plays a sport that involves near-constant running, was able to return after missing just two games, whereas Puig, who does a lot of standing around in baseball, still has a long way to go to get back on the field.

The severity of their injuries likely has something to do with that, of course, but so does the nature of their positions. As a point guard, Paul can control the tempo of a game, and bring the ball upcourt at his pace. There are movements that can put extra strain on his hamstring — jumping, cutting to the basket — but he can largely protect his body from the rigorous demands of certain motions.

Puig, however, needs to go from a standstill to a full sprint, when he’s trying to beat a throw to first, run down a ball hit to the gap or race to the wall to attempt a leaping catch.

“There are baseball players who have mild hamstring strains that you probably don’t even know about, who play with them and don’t get hurt,” said Stan Conte, Dodgers vice president of medical services. “There are other guys who came back and were able to run really hard and play about five or six games, and then injured it again. And the second injury is always worse.”

Dehydration and fatigue are significant factors that can lead to a hamstring problems, and people who have had one such injury are highly susceptible to a second. That’s because scar tissue forms and makes a healed hamstring even less elastic.

Explained Gary Vitti, head trainer for the Lakers: “At some point, if the load isn’t transferred from the upper torso through the pelvis and into the leg in the right mechanics, the load will go to the weakest link in the kinetic chain and if that’s the hamstring, then the hamstring will start to come apart.”

The Steelers’ Bradley, who has done extensive studies on hamstring injuries, is a leading expert when it comes to using platelet-rich plasma to treat them. That involves drawing blood from the athlete, spinning it in a centrifuge to separate the healing platelets, then injecting those platelets back into the injured area.

“By using that, we’ve decreased the time they were out by about a week,” said Bradley, whose brother, Tom, is the new defensive coordinator for the UCLA football team. “In the NFL, a week is a lifetime. But more importantly, in the group we studied, the re-tear rate in the same spot went down to almost zero.”

Podesta, team physician for arena football’s L.A. Kiss, uses a portable ultrasound device to instantly diagnose the severity of hamstring injuries. The images appear on his laptop, and he can instantly recognize a tear. On the screen, the fibers of a healthy hamstring all run in the same direction and look like the vanes of a feather; a tear might show up as a dark slash that cuts across and disrupts those vanes.

And, of course, an athlete will be aware of the injury by the sharp and typically debilitating pain.

When he was playing for the Carolina Panthers, receiver Steve Smith suffered three hamstring tears in a two-month span, two in one leg and one in the other.

“A hamstring is the unsung hero of a person’s career on a day-to-day basis,” Smith said.

You don’t think about it. Until you can’t stop thinking about it.

Twitter: @LATimesfarmer

Times staff writers Ben Bolch and Mike Bresnahan and correspondent Steve Dilbeck contributed to this report.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.