It’s a pretty shaky suspension bridge for Manny Ramirez

While the Dodgers were playing the 42nd game of Manny Ramirez’s 50-game suspension Tuesday, Manny Ramirez was doing something very strange.

He was playing for the Dodgers.

Well, not exactly, but close enough, as he was playing on a Dodgers-sponsored team, with Dodgers-funded teammates and coaches, in a stadium where a portion of the ticket revenue is sent to Major League Baseball.

Manny Ramirez playing for the triple-A Albuquerque Isotopes is as weird as the word “isotope.”

Why is Ramirez allowed to play there? Why is Ramirez allowed to play anywhere? Since when are players allowed to turn a rehab assignment into a detox assignment?

And why can’t baseball punish a guy without also apologizing to him?

Sorry about those 50 games, slugger. You can use our minor league club to get back in shape before the suspension ends, come back at full strength, is that OK?

Under the current rules, I don’t blame the Dodgers for sending him there, and it’s hard to blame Albuquerque for trying to make a few bucks off the circus, but there is something fundamentally wrong about all of this. I blame the entire Major League Baseball system -- from the commissioner’s office to the union to the individual clubs -- because nobody saw this coming.

When negotiating the drug policy three years ago, baseball officials felt they had to allow for minor league rehab assignments in order to get union agreement on a 50-game suspension total. The union was claiming that, otherwise, with the player needing to get back in shape, the suspensions actually would amount to more than 60 games.

Officials were also receiving pressure from their clubs to allow the players to do rehab assignments during the suspensions, instead of later, so the teams did not have to pay the players while they were in the minor leagues.

In the end, the baseball bosses were so desperate for any sort of penalty, they caved in to everybody. And perhaps they hoped that everyone would be so happy the druggies were finally being punished, nobody would notice.

Well, today, we all notice.

Today, a suspended baseball player is back on a field playing baseball and making money for the same people who suspended him.

Today, a shamed drug offender is basking in the national attention and adulation created by the same people who shamed him.

Today, a troublemaker who is currently being suspended from high school is enjoying private tutoring from his teachers in a simulated classroom environment filled with students, and where’s the learning in that?

This is not the first time this has happened this season, as the Philadelphia Phillies’ J.C. Romero quietly made five appearances in the minor leagues before completing his 50-game substance suspension.

Did it help? Well, Romero began his season with six consecutive scoreless games, and has given up one run in nine innings so, yeah.

Romero is a fairly anonymous middle reliever and didn’t grab the national attention of Ramirez, but it was wrong then, and it is wrong now. Baseball needs to fix it before it happens again, and baseball knows it.

“This has never been a point of contention before,” said Pat O’Conner, Minor League Baseball president. “But it’s a whole new era.”

Currently, O’Conner’s teams don’t have a choice but to accept players such as Ramirez. Major League Baseball is in the middle of a 10-year agreement with Minor League Baseball that includes what is known as the “Rule 9(i) rehab.”

The rule allows suspended or injured major league players to spend 10 days (hitters) or 16 days (pitchers) in the minor leagues before returning to the active list.

“We can’t pick and choose who we’ll accept,” O’Conner said. “Suspended players, injured players, it’s apples and apples.”

He paused, and acknowledged that the Ramirez case is unique.

“This is a different kind of apple,” he said. “This is one for the ages.”

Talking with O’Conner and major league officials Tuesday, it became apparent that the Ramirez case has caused both parties to reconsider Rule 9(i), and it will be revisited this winter.

“It’s a new era, and would something like this be deserving of at least a conversation?” O’Conner said. “Maybe so.”

In the meantime, Ramirez’s suspension continues to look increasingly like a nice vacation for him and a financial windfall for the Dodgers.

Think about it. During the suspension, Ramirez had reaped all the rewards of being a Dodger without any of the responsibilities.

He has been allowed clubhouse and training room and field access without ever explaining how and why and when he violated baseball’s drug policy. The Dodgers have taken care of his every need -- from cough syrup to batting-practice baseballs -- without once asking him to be accountable to the community that they once considered a priority.

The Dodgers so value Ramirez’s comfort above all else that they actually sent employees to Albuquerque to help him and protect him from the unwashed masses who would dare bother the great man during his courageous comeback from a female fertility drug.

I guess that’s cheaper than hiring a midwife.

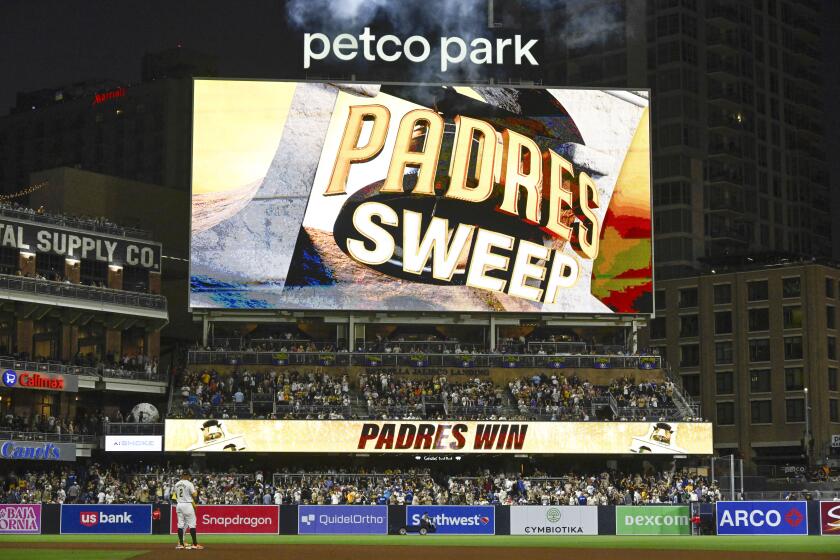

All of this is set up to fill stadium seats and company wallets upon Ramirez’s July 3 return. Did you hear about the previously planned bus trip to San Diego for the Padres series on Fourth of July weekend? In an e-mail sent to fans, a Dodgers employee re-billed the trip as a welcome back for Ramirez, exploiting a drug offender in only a slightly more sophisticated manner than the dude standing on a darkened corner of Sunset.

And, c’mon, after watching fans fill up the yard in Albuquerque, is there any question that the Dodgers will re-christen the “Mannywood” section the moment he returns to Chavez Ravine?

When Manny Ramirez is old and gray and sitting outside the locked doors of Cooperstown, he might reflect on this summer as the best 50 games of his career. Or is it 42 games? Or, really, was he ever gone?

It’s all Isotopes to me.

--

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.