SET DESIGNER DEFINES FUTURE FOR HOLLYWOOD

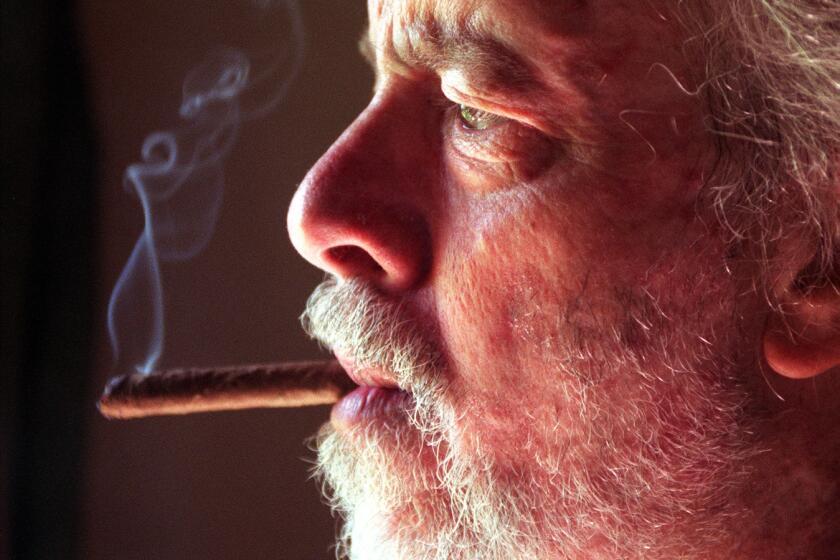

Syd Mead isn’t the kind of guy you’d expect just to walk into a room. The architect of future worlds for forward-looking films such as “2010,” “Blade Runner,” “Tron” and “Star Trek: The Motion Picture” might be expected at least to beam down via a molecular dematerializer.

But on a recent afternoon, Mead, looking unassuming in plaid sport coat and gray corduroy slacks, simply walked down the movie theater aisle, like any other humanoid from the last quarter of the 20th Century, to address an audience of about 300 UC Irvine students.

So much for expectations.

Most distressing, however, was one moment after the screening of “2010,” which was part of the Theatrical Film Symposium course offered through UCI’s film studies program. When Mead picked up the microphone to speak, not a sound emerged. He had forgotten to push the mike’s “on” button.

“A master of high tech,” joked symposium teacher Thomas Girvin, who shared the stage with Mead. (Each week, Girvin brings in one or more guests who were creatively involved with the movie being screened.)

Besides providing some comic relief, the incident underscored a point Mead emphasized about his visions of the future: no matter how sophisticated technology becomes, it will always be subject to human foibles.

“I like to create alternatives of the future,” said Mead, 52, whose formal education was in industrial design at Art Center College of Design in Pasadena.

His illustrations of these alternative futures are currently on exhibit at the California Museum of Science and Industry, Los Angeles, and Mead will lecture at the museum’s Kinsey Auditorium on Saturday at 11 a.m. and 1 p.m.

The key to a successful design, said Mead, whether it be as elaborate as a whole spaceship or as simple as a door, is that “it has to look like it would do what it is supposed to do. A lot of movie props look like a design rather than like a real machine.”

Mead first makes tempera paintings of his designs, which the movie production crews use to turn his visions into reality. For the Russian spacecraft Leonov Mead designed for “2010,” he said, “I put together a vehicle that looked clunky. I figured that a Russian spacecraft would be over-engineered because they know their jobs are on the line if something doesn’t work.”

There are, however, some guidelines in addition to basic logic that must be followed. Dramatic license sometimes favors less realistic designs that are more “sexy,” Mead said. But perhaps the most restrictive factor is audience expectations.

“An audience pays to see a film, and people expect things to look a certain way,” Mead said. “If they look too different, people will have to stop and figure out, ‘What the heck is that supposed to be?’ and the continuity will be wrecked. So you have to relate it to some reference points in their memories. That’s why I started with a Boeing 757 cockpit for the interior design (of the Leonov).”

What’s the secret of satisfying movie directors or other customers?

“I make a client feel like it’s his idea and I’m helping him realize that idea,” Mead said. “You have to do that if you want people to ask you to come back and do repeat business.”

Mead said he is personally proudest of his contribution to Ridley Scott’s 1982 film “Blade Runner,” for which he designed virtually the entire set depicting a bleak, decaying Los Angeles of the 21st Century.

“I was originally just supposed to create some vehicles for the film, but Ridley Scott liked the backgrounds I had done in my drawings of the cars. From there, I ended up doing the wet streets, the buildings --everything down to the fire hydrants and things people would never see.”

An industrial designer who has worked for major corporations such as General Electric, Ford Motor Co., Honda, Philips, Lear and others, Mead made the transition into motion pictures in 1979, with the first “Star Trek” feature film.

Special effects-production design wizard John Dykstra was familiar with Mead’s book, “Sentinel,” which contained his illustrations of futuristic architecture, transportation systems and computerized environments.

“They were working against a tight deadline, and at that point they had literally no visual clue for V-Ger, this thing that was threatening Earth. So Dykstra contacted me, and I essentially came up with the idea for V-Ger after three or four weeks of very hard work, and we made the deadline.”

His work in space designs, however, isn’t strictly fictional: it was Mead’s illustrations that were used by NASA for the interior of Skylab. He was recently commissioned to design a poster for display in the Smithsonian Institution.

A Capistrano Beach resident since 1975, Mead works primarily out of an office in Hollywood. He is currently working on a new science fiction film, about which he offered only minimal details.

His other projects include designs for “private 747 (jumbo jet) interiors, a 145-foot futuristic sailboat for a multimillionaire in Canada for private 747 jets, a theme park in Montana and (serving as) a judge for the Miss U.S.A contest.”

Despite his renown as a designer of futures, his interests aren’t all focused on the days and years to come, as evidenced by the classic 1956 gull-wing Mercedes he drives (though he was quick to point out that “it was the car of the future 30 years ago”).

While some movie industry insiders complain that their business isn’t nearly as glamorous or exciting as most of the public perceives it to be, Mead has no complaints about his his job.

“It’s a very enjoyable process,” Mead said, “because you are getting paid for how you think.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.