Couple Sue School District Over Son’s Suicide

When Jesse De Jesus killed himself between classes at Canyon High School, he left an extensive record of his battles with internal demons.

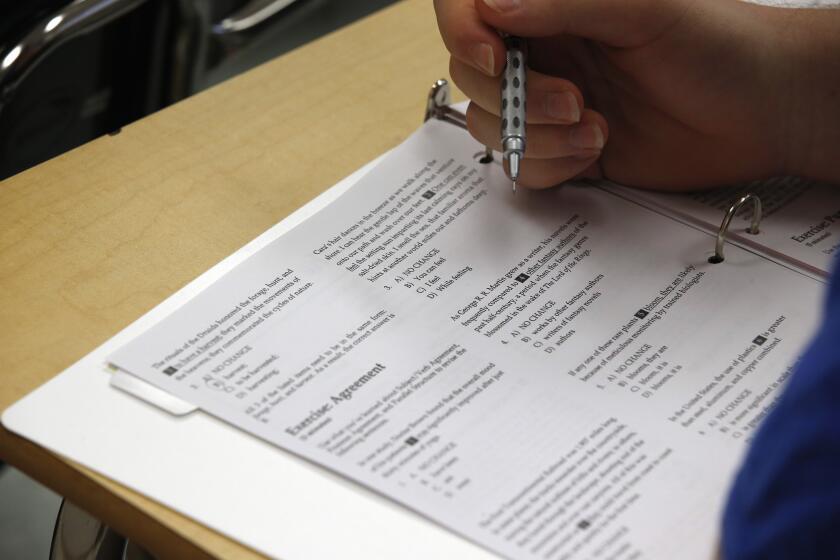

“My mind is filled with poison, just like they said,” the 16-year-old boy wrote in one of the many essays he was required to compose as punishment for disrupting class. The essays were supposed to address his talking and clowning, but he used them for more. In disorganized, rambling sentences, he poured out his anxieties and frustrations at school.

“Dear Canyon Country . . . Have you ever heard I would die for you?” he wrote in the suicide note that he left under his bed on the morning of Jan. 13. He walked to an open area between the school and a nearby park that day and shot himself in the forehead, authorities said.

This stark log of a boy’s journey into despair is part of a novel legal challenge that attempts to put the blame for the death of the friendly, inwardly directed boy squarely on the school system. His family is asking for unspecified damages against the William S. Hart Union School District in the suit filed last month in Los Angeles Superior Court.

“They did it, they did it to him,” Olga De Jesus, Jesse’s mother, said angrily. Rather than build her son’s confidence and help him learn how to cope in society after high school, teachers called him names and made him feel like a failure, she said.

The unusual case is expected to focus not only on the volume of written material showing Jesse’s frustrations in school, but on the special responsibility given educators to help students with learning problems.

“The education code requires that once you recognize these kids and diagnose them you get them the attention they need,” said the family’s attorney, Marcelle Philpott-Bryant. “If it means psychological care, you must do it. It’s a legal obligation.”

The school district and its teachers have refused to comment, although some observers have challenged the parents’ suit, characterizing it as an attempt to blame someone else for the tragedy.

Wider Impact

Cynthia Crosson Tower, a Massachusetts author of several books about child abuse, said it is apparent that Jesse De Jesus fell through the cracks somewhere. “But it could predate this school,” she said.

Other educators worry that such cases could pose a wider threat. “I have an abhorrence of the courts getting involved in the schools,” said Bill Honig, state superintendent of public instruction. Too much interference will make it increasingly difficult for teachers to do their jobs, he said.

If the case reaches trial, Canyon High could find itself asked to explain more than just the death of one troubled student. Attorney Philpott-Bryant said two other students, including respected athlete Julie Tate, committed suicide in the past three years.

Grief counselors were critical of the way the school handled her death. They said the school seemed to glorify her with a wreath in the office and a large picture in the yearbook.

“Kids get the idea, if you don’t get positive reinforcement in your lifetime, this at least happens after your death,” one observer said.

Jesse’s friends said he was quiet but never shy. They said they never heard him talk about suicide.

“Before he died, we prayed together that things would get better because he was kind of down,” said Brian Ihms, another special education student who lived a few streets away from Jesse. The close friends--Jess and Bri to each other--prayed that “we would graduate, get nice jobs, and have a grand old time,” Brian said.

After Jesse killed himself, Brian said, he became depressed and considered suicide. Instead, he walked to their favorite spot in a pasture and carved into a tree, “J and B forever.”

Jesse De Jesus was the youngest of five children of Olga and Julian De Jesus, Puerto Rican immigrants who came to the United States “for the same reason everyone is here, a better living,” said Julian De Jesus, an electronics technician for Sears, Roebuck. In the past three decades, they have become so fiercely Americanized that his wife, an accounting clerk for a San Fernando Valley fabric store, admits to getting angry when she hears people speaking Spanish instead of English.

The family originally settled in Chicago, where a daughter was paralyzed when she fell from a tree. Then there was dreamy Jesse. His mother said she noticed early that “he was too much of a home type for a little boy.”

In kindergarten, he had drowsy spells, diagnosed at a local hospital as petit mal seizures associated with epilepsy. He was treated with Ritalin, a drug for hyperactivity. The drug helped him concentrate, his parents said, and the seizures later went away on their own, after he was hit by a car crossing a street near his home.

Despite his problems, his mother said, Jesse got along fine at home. “He wasn’t shy, but he was quiet,” she said. “He would lie there and watch TV hour after hour” in the living room of the family’s 2-story house in Newhall.

Like his parents, the boy had all-American dreams. Brian said Jesse talked about getting good grades and succeeding in life. But Jesse wrote that studying was a lot of work, and he found it hard. Special education students are loosely classified as “learning disabled” and possibly mildly retarded, with IQs in the 69 to 85 range.

Olga De Jesus said things began going downhill for Jesse in his second year at high school when she began receiving calls at work from teachers about his behavior. She said she tired of hearing the complaints, but things just got worse in Jesse’s third year.

“Almost every day they were calling me at work,” she said.

Jesse was convinced that he was being picked on. “ ‘Mom,’ he says, ‘do you believe them?’ I said, ‘No, I believe you because I know you,’ ” she said.

On the Monday before he killed himself, she said, she found him lying in bed leafing idly through a school yearbook, even though he was not in it. And on Tuesday, she said, he refused to eat her fried chicken, a dish he loved. The next morning he arose early, ate a grilled cheese sandwich and headed out the door for the 3-mile walk to school, she said. He left the front door open, which Olga De Jesus said she thought odd.

Found too late under his bed was a note addressed to the school. “I could have been a dreamer or a shooting star,” it concluded.

To Jesse’s friends, his act was bewildering. But they saw some of the strains. Brian said Jesse probably did disrupt class.

“He liked to socialize,” said Robert Hartman, who had a class with Jesse.

Robert said one teacher seemed to have it in for Jesse. “He would say, ‘You’re stupid, Jesse, you’re not going anywhere in life.’ ” He said the teacher kicked Jesse’s chair when he walked by, and accused him of taking drugs and falling asleep in class. Jesse was taken off Ritalin at age 12.

Jesse “maybe got high once in a while,” but he was sleepy, Hartman thought, because he had to get up early.

While strict rules govern the use of physical discipline, educational law attorneys said, there are few guidelines that tell teachers how to apply other types of discipline. But educators worry about attempts to set down such guidelines.

“The more involved the courts get, the more paranoia and animosity” they arouse in teachers, said William White, principal at Canyon High.

Special Education Needs

Life dealt Jesse a tough hand from the start, and some might say his cards never got much better. Olga and Julian De Jesus said they loved their son and did their best for him. The school insists its teachers are skilled and caring. But a note in his school file dated April 29, 1987, said: “He’s apathetic. He has very poor self-esteem. Something needs to be done.”

Jesse’s profile shows many of the characteristics discovered in other special education students in a recent three-year study by the USC. Andrea Zetlin, one of the principal investigators, said the study of 60 students showed that compared to normal students, special education teen-agers are not learning proper social skills and have trouble becoming independent and adapting to life outside their families. The 20 teen-agers who found part-time jobs held 37 different ones, which usually paid minimum wage, the study found. Many lasted no more than two or three months before they were fired.

She said she found “incredible amounts of depression” among group members as they faced rejection and failure.

Despite special programs, the education system is not doing enough to prepare special education students to stand on their own feet, Zetlin said. But she said parents also make mistakes, particularly in sheltering their children too much. Parents sometimes allow children to sit in front of the television all day, she said.

Even a good parent can make mistakes of the heart with such children, she said. Normal children ask for freedom as they grow older, and parents must decide how much to grant. But, she said, “What if the kid doesn’t ask for freedom” and is content with his or her dependent life? Many parents tend not to push sons and daughters out of the nest, she said.

Homework Undone

Jesse’s records contain references to homework left undone.

“There were many times when I asked him about his homework,” his mother said. “But at the end, I didn’t see any homework. The poor kid got so fed up he didn’t want any part of us telling him.”

She expressed the frustration of being a working mother with a child with extra needs.

“As a mother, I do whatever I can. I work, I have to work. If we want to get ahead in life, the only way we can do it is with both paychecks,” she said.

Still to be settled in court is how much responsibility Jesse shouldered for his suicide. He was the one who found the gun with the serial numbers obliterated, and he pulled the trigger. His writings show how much trouble he had with responsibility: “I like to do good, but it requires a lot of hard work, and it’s not fun,” he wrote.

Philpott-Bryant, the attorney, said the school system not only did not meet Jesse’s special needs, but destroyed his feelings of self-worth. She said she counted 27 punishment essays in his file.

More to Read

More to Read

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.