Angelenos on Edge From Continuing Aftershocks : Aftermath: Each major jolt--like Thursday’s 4.5--sends the skittish scurrying. But some just shrug the shakers off.

With each major aftershock, the cracks riddling every corner of Renee Cronenwalt’s house grow a little bigger and she grows a little glummer.

“There’s a subtle feeling of whether we had the Big One or the Big One is yet to come,” said Cronenwalt, who lives off Mulholland Drive in what was a big, beautiful house. “We had a lot of damage in our house, and every time we have an aftershock we have a little more damage and I’m overwhelmed with all the work that needs to be done.”

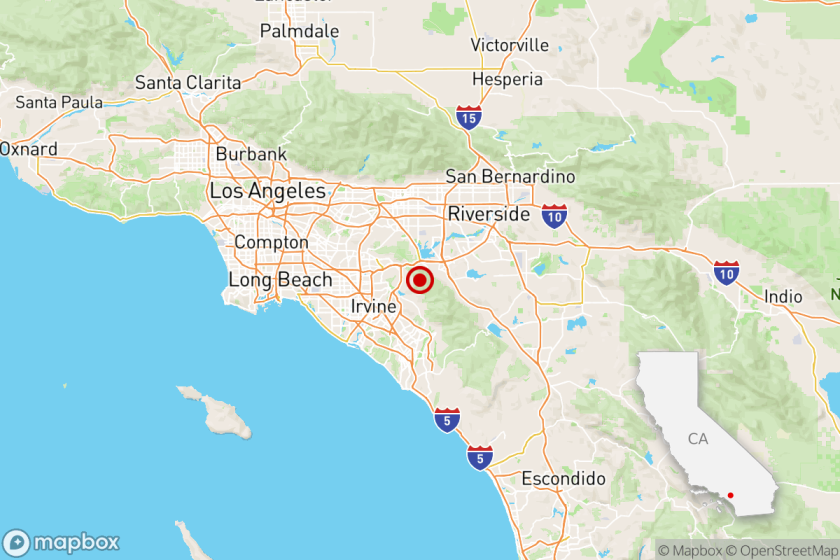

Creaking and groaning like a giant settling into a new seat, the Los Angeles Basin has been hit by more than 3,000 aftershocks since last week’s 6.6 magnitude earthquake in Northridge--including a 4.5 magnitude aftershock Thursday morning--and seismologists are still counting. Hundreds have been strong enough to be felt, robbing people of a sense of everyday security. No sooner do the grinding sounds and frightening images of last week recede than a jolt revives them. It has become the disaster that just won’t go away, turning the quake-weary into skittish cats.

Ruth Stubba is one of those for whom the aftershocks are more traumatic than their 6.6 precursor. “The aftershocks are the most unnerving,” said Stubba, whose Thousand Oaks home survived the Jan. 17 temblor undamaged. “They just don’t stop. Thirty seconds was one thing. But all the others are adding up to much more than 30 seconds.

“I find that no matter how long between them, my nerves are right on the edge. As soon as one hits, I’m shaking again.”

Bobbette Fleschler of Chatsworth braces herself during every aftershock and jumps at the slightest noise, wondering what is coming next. “Oh no, here we go again,” she thinks. Her 3-year-old daughter, Aviva, who slept through the Jan. 17 quake, has a more dramatic reaction to its aftershocks. She falls to the floor and pounds it with her fist, exclaiming “Now that’s enough! Stop that!”

Thursday morning’s aftershock sent the staff in Howard Bragman’s public relations office diving under their desks for at least the sixth time in the past 10 days. “There’s no shame in our being under our desks. We’ve learned to like it,” joked Bragman, whose Beverly Hills office has lots of glass.

Last Friday, when a swarm of aftershocks roiled the region, Bragman took his phone under his desk and started making business calls from there. His dog--which he often takes to work--joined him. He also spent a lot of time calming his staff. “I had three different people come in and break down. One person just went away for the weekend. . . . A second person went to visit her family in Florida for the week.”

*

After nearly two weeks of shaking, aftershocks have started to take on the routine of wartime air raids, just one more disquieting twist to life in Southern California.

“I’ve finally gotten used to it,” said Carmen Roldan of Silver Lake. When a 3.8 shaking hit Wednesday morning at almost exactly the same time as the Jan. 17 quake, Roldan simply rolled over in bed. “I said, ‘That’s it, I give up.’ You just have to go on.”

Then there are those who greet the continuing jostling with the bravado of veterans, shrugging off the aftershocks with barely a second thought.

“I’m a salesman, nothing bothers me,” declared Steven Rosenthal, whose office is in Van Nuys. “I hope a lot of people move out,” he said, grinning. “It’s too crowded. If this scares ‘em--good. Less traffic for me.”

Rosenthal no doubt fits into the first of three coping categories described by Dr. Louis Jolyon West, a UCLA professor of psychiatry. Those who cope the most easily are highly adaptive, becoming less anxious with each aftershock. “Through a process of what can be called emotional learning, they have learned what the parameters of risk might be” and can reassure themselves.

Those in the second group, encompassing perhaps the largest number of people, respond about the same to each repeated stress, in this case, aftershocks.

But for the third group, each aftershock makes things worse.

“There’s an accumulative stress response,” West explained. “It’s almost as though with each progressive repetition of stressful experience, their ability to cope decreases and their emotional reaction increases. They become more and more vulnerable.”

People subject to that cumulative effect will suddenly burst into tears or decide they have to get out of town.

“The aftershocks here just keep bringing it right back to everybody’s consciousness,” observed J. Richard Elpers, a professor of psychiatry at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. “Part of healing is to get some sense of security back and getting back to normal things. . . . Each aftershock will delay that process and remind us of what we’re afraid of.”

Because they are so unpredictable, earthquakes are in some ways more terrifying than other natural disasters. And each shaker of the past two weeks reminds people of that unpredictability.

The ongoing quakes are exacting a particularly hard psychological toll in the traumatized San Fernando Valley--the big quake’s epicenter.

Although authorities have pronounced his Reseda apartment safe to re-enter, Jeff Estrin is still too nervous to go back.

“I have a hard time going back to my apartment, especially my bedroom,” Estrin said, his voice shaking. “I went back and sat on my bed but the anxiety builds up and my heart begins to race and I have to leave.”

The quake knocked Estrin’s entertainment center to the ground, and when he put it back up, an aftershock knocked it down again.

“I have lived through other earthquakes. I don’t remember them (aftershocks) being so long and so hard,” said Estrin, who is staying with his sister-in-law, Gena Estrin. “They are kind of like ‘Boom! Here I am.’ ”

Thursday’s magnitude 4.5 aftershock prompted some parents to pick up their children from Valley schools. At Osceola Elementary in Sylmar, students in one class sat on the floor hugging stuffed animals they had brought to school at their teacher’s suggestion.

At some Red Cross shelters in the Valley, people rush outside at every strong aftershock. Some get hysterical. “If you are constantly in fear you can’t (get) beyond that,” observed Raedeen McGowan, a Red Cross assistant mental health officer who flew in from Omaha to offer counseling to quake victims.

The daily shaking is giving her a first taste of life on the fault lines. “For many of us this is our first opportunity to come out and shake and roll with you folks,” McGowan added. “I know I kind of lie awake and think, ‘When is this going to happen?’ ”

*

Even far from the epicenter, in places where the Northridge earthquake barely nudged the furniture, the steady succession of aftershocks has kept people on edge. “It made me realize it is not that far away,” Debra Washington, a clerk at the South Bay Pavilion shopping mall in Carson, said after Thursday morning’s quake. “We all live in Los Angeles.”

Joan Gardener, a manufacturers’ representative who works out of her home in Monrovia, chuckled nervously. “I just keep wondering how long our luck here will hold,” she said. “The San Gabriel Valley has been really unreasonably lucky.”

Athens-area resident Noel Garcia, who works at a sporting goods store in Carson, said he has come to regard earthquakes as nature’s version of drive-by shootings and robberies: There is nothing anyone can do about them.

“It could happen right now, right here, just as we are standing here,” Garcia said. “Unfortunately, it is something you have to live with in L.A.”

Even when there aren’t any aftershocks, the hypervigilant feel what some are calling “phantom quakes.”

“I have felt more aftershocks than there have been,” admitted Stubba. “I’m at the photocopy machine and I think, ‘Oh, my God.’ There’s a motion problem that’s not over yet.”

The rhythm of temblors has made for many a sleepless night for Darin Flannes of Santa Clarita. Still, he says, his newly torturous commute to work in the San Fernando Valley is worse. “I can live with the aftershocks a lot better than the freeways. There’s no way I can get used to a three-hour journey in the morning.”

Times staff writers Chau Lam, Beth Shuster and Dean Murphy contributed to this article.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.