How They Got From There to Here in Jazz

Lenora Zenzalai Helm is an exciting, cutting-edge vocalist and composer, profoundly committed to her art and deadly serious about being an advocate for women’s equality in the male-dominated jazz world.

So when a horny male club owner hits on the strikingly beautiful singer, offering a gig for sex, she’s appalled and speaks her mind right away. It’s little wonder that she’s the president of International Women in Jazz, an organization dedicated to improving the welfare of women in jazz.

“I’ve had a direct come-on like, ‘Well, you can get a gig if you sleep with me.’ Or a line like, ‘When are you finally going to get with me? When are you going to stop making me wait?’ Some club owners are used to people accommodating that kind of come-on, so they do it because they’ve been successful in the past,” Helm says from her Manhattan apartment.

“Most of the time they just shrug off rejection and say, ‘Oh, you’re uptight,’ or ‘I didn’t mean anything by it, baby,’ or ‘You’re really cold.’ Or sometimes they’re embarrassed by being shot down. And, of course, I lose the gig,” Helm says.

“When I was just learning the business, I was a lot more timid and would just carry my anger away with me. I’d curse them under my breath, saying that’s one more person I won’t be able to work for.

“Now I’m pretty assertive and vocal about it because I figure that’s a ‘teachable moment’ for the moron. And the next woman won’t have to deal with it.”

That’s just one glimpse into the seedier side of what a female jazz musician may sometimes run into. And it’s just one piece of an overall view of the trials and tribulations--but also the triumphs--of women in jazz as presented in interviews with Helm and three other female jazz performers.

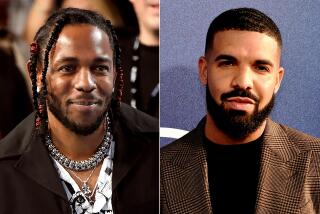

The four range in age from Erica vonKleist, 18, a jazz wunderkind, to the celebrated Marian McPartland, a still-youthful old master at 82.

A gifted saxophonist, clarinetist, flutist and composer-arranger, vonKleist is from West Hartford, Conn. She plans to go to school this fall at New York’s Manhattan School of Music.

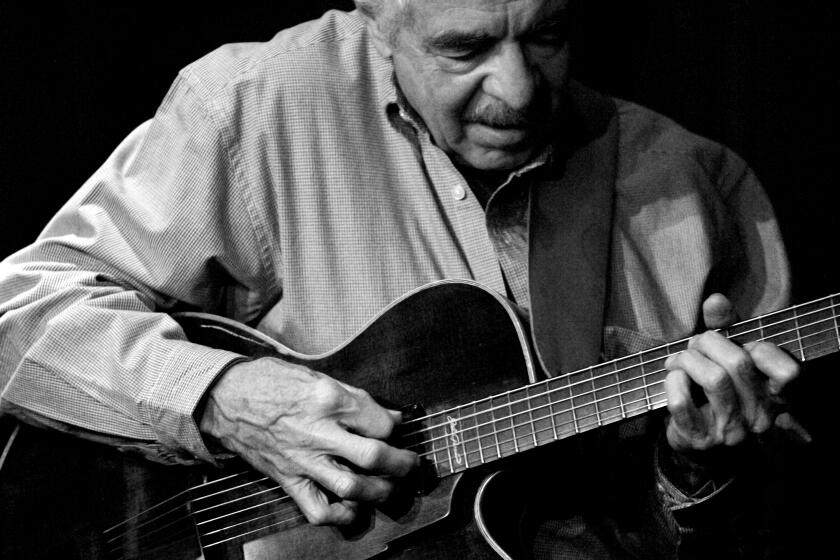

McPartland long ago conquered the Big Apple after coming to the United States with her then hard-drinking, brilliant, famous cornet-playing husband, Jimmy McPartland. Besides making more than 50 albums, the ruggedly independent pianist has found success with her award-winning National Public Radio show “Piano Jazz” and with her original compositions. In a groundbreaking action for women in jazz, she once ran her own small, classy record label entirely by herself. She has also won acclaim as a writer of a collection of worthy jazz essays called “All in Good Time” (Oxford University Press, 1987).

Helm, 39, is hoping at long last to make a major breakthrough with her new, critically acclaimed album, “Spirit Child” (JCurve Records).

The other female is Sue Terry, 41, a successful alto saxophonist. Both as a busy sideman and co-leader with her husband, pianist John di Martino, of the group Terra Mars, Terry has found success in New York City, the Darwinian jungle that devours the dreams of success of many a budding jazz musician--male or female.

Each of the four comes from radically different backgrounds. Helm grew up in a housing project in Chicago. VonKleist and Terry grew up in Connecticut suburbs. McPartland was born in England and raised by a quite proper, conservative family. Her parents were appalled when she ran off as a teenager to play in a pop piano quartet touring British vaudeville houses.

Not surprisingly, each has a highly individual take on the status of women in jazz today.

Lenora Zenzalai Helm

My mother thought I was going to go to Cornell and study medicine, so when I told her I had applied to Berklee College in Boston, she had a fit. “No, Mom, I’m going to music school,” I told her. “Well, then, you can still be a singing doctor,” she said. But jazz was the only thing that made the hair stand up on the back of my neck. I was mesmerized.

There are still chauvinists out there. But there are signs of progress. You do have women who are in charge of booking major artists, or who are in charge of large departments at record companies, or are running jazz clubs. So women are more in the driver’s seat in certain areas. But they had to earn it tooth-and-nail.

It’s hard to change a paradigm, especially an evil, deep-seated one like sexism. There still are men out there who show disrespect to women. For example, a club owner will pass right by me, go right up to one of the guys in my band, and pay him for the gig. The owner just automatically assumes a woman couldn’t possibly be in charge.

There are times when I have just broken down to tears because it’s a hard business. And sometimes at the end of the day, when you don’t have your rent, and you don’t have any work on the books, and your record isn’t selling, and you’re fighting with your record company, you have to remember why you even got into jazz in the first place. Then I just go to a piano and sing, and I’m reminded of the grace of God and of what the point is.

Marian McPartland

When I first came to the United States, people were always saying patronizing things like, “Oh, you play good for a girl.” Or, “You sound just like a man.” I was new to the business, so I took everything as encouraging. But then I started to think about it and ask people what they meant. Or they would say I played “aggressively.” Then I would say, “You wouldn’t say that if I was man.” I’m not aggressive. It’s just that I can play strong. And why shouldn’t I? Sometimes I would argue with them, and they would back down.

My parents thought my love for jazz was just a passing fancy. My father said to a teacher at my school, “What shall we do with her?” They never really understood back then but were proud of me later. “Why can’t you get married and have children, or meet a nice man?” they wondered. My mother said, “You’ll come to no good. You’ll marry a musician and live in an attic.”

Once, one of my uncles--one who had been knighted by Queen Elizabeth II--came over to America and saw me playing at the Hickory House. He was in shock. He said, “Marian, does your father know what you’re doing?” I think he disliked the fact that the bandstand was up behind the bar and I was surrounded by liquor bottles. But he got over it.

Sue Terry

I never think of myself as a victim. Being a woman playing jazz is an advantage, especially in this country, where people love to root for the underdog. I personally like being surrounded by men. So I never had a problem in a mostly male world. Of course, I still hear things like, “Gee, I never saw a woman play the saxophone.” Or, “I never knew a woman could play like that.” My first reaction is, “Well, where have you been? Have you been sleeping? Women saxophonists have been out there since at least the ‘40s, and this is the year 2000. Hello!”

I try to steer clear of all situations where you’re hired more as an object of desire than as an artist. I want to present myself first and foremost as an artist and secondly as a woman. I think this is a good time for women to be emerging in various fields, not just jazz. Society is more open to this. There’s more freedom for women now in this country. And as far as jazz as a career goes for women, they say you can’t really choose it. It chooses you.

Erica vonKleist

When I step out into the world, I’m not expecting to become very comfortable and live in a big loft apartment in New York City, plan big weekends and make $900 a gig and have everything just be wonderful.

I think part of the fun is just getting down and dirty and saying, “OK, I have $5 to go on for food for the week. How am I going to make this work?” That’s part of the fun, and makes you a stronger person. I’m prepared for it mentally. I know it’s not going to be easy when I get there.

Whatever happens, happens. I don’t have a so-called backup plan, no plan B. I’m going to make it work, eventually writing and playing music for a living. What I get from jazz is the satisfaction of completing something, of doing something to my best.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.