What do George Orwell and Winston Churchill have in common? A new book has the answer

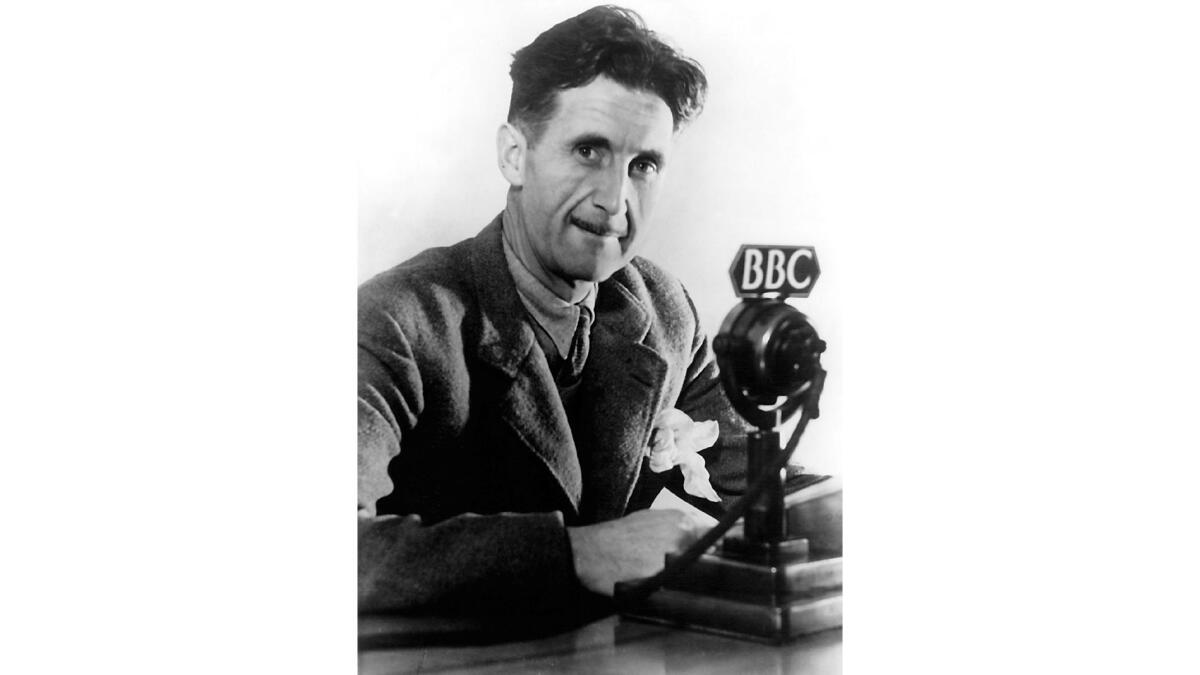

Beyond membership in the Pantheon of Famous Brits, Winston Churchill and George Orwell would seem to have little in the way of common ground. Churchill was a politician. Orwell was a journalist and novelist. Churchill had money and pedigree; the young Orwell lived on the street and raised his own vegetables during World War II. Churchill’s political leanings were conservative; Orwell flirted with communism until he witnessed the betrayal of his Republican comrades by Soviet agents in the Spanish Civil War.

In “Churchill & Orwell: The Fight for Freedom,” Thomas E. Ricks gets beyond these differences and finds the iron core of both men. These two were pillars of the 20th century struggle against “the twin totalitarian threats of fascism and communism,” Ricks argues. “Churchill’s flamboyant extroversion, his skills with speech, and the urgency of a desperate wartime defense led him to a communal triumph that did much to shape our world today. Orwell’s increasingly phlegmatic and introverted personality, combined with a fierce idealism and a devotion to accuracy in writing, brought him as a writer to fight to protect a private place in that modern world.”

Both men shared this unshakable belief: that their audience deserved the truth.

Why Churchill AND Orwell?

Many books have been devoted to Churchill, including his six-volume memoir of World War II. Orwell is considered a secular saint among journalists for his unblinking reporting on war and social issues. His novels “Animal Farm” and “1984” have become go-to texts for readers struggling to understand the roots of authoritarianism. Ricks, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter and author of “Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq,” compares the two, highlighting not just their skills and strengths, but the tumultuous times that demanded the highest exercise of their talents.

Both men were mesmerizing writers, though with different styles — Churchill was a master of rhetoric; Orwell a superb essayist. Both blurred the line between soldier and journalist; Churchill in the Boer War, Orwell in the Spanish Civil War.

Though they were born on opposite sides of the English class divide, they both lived with the “impossible burden” of disappointed fathers — when Churchill was finally accepted to the military academy Sandhurst after three tries, Lord Randolph Churchill wrote to his son: “You will become a mere social wastrel one of the hundreds of the public school failures, and you will degenerate into a shabby, unhappy & futile existence.” Orwell saw little of his father, whom he described as “a gruff-voiced elderly man forever saying ‘Don’t.’” Both endured long stretches when they seemed destined for failure.

Yet they were both visionaries, though the vision could be very dark indeed. Churchill showed his devotion to the English people by telling them just what they were up against. Ricks describes Churchill’s August 1940 address to the House of Commons as “Orwell-like in its sobriety and its sparse accuracy.”

Churchill tallied the accumulated catastrophes of his first months of leadership:

“Rather more than a quarter of a year has passed since the new Government came into power in this country. What a cataract of disaster has poured out upon us since then. The trustful Dutch overwhelmed; their beloved and respected Sovereign driven into exile; the peaceful city of Rotterdam the scene of a massacre as hideous and brutal as anything in the Thirty Years War. Belgium invaded and beaten down. … our ally, France, out; Italy in against us; all France in the power of the enemy, all its arsenals and vast masses of military material converted or convertible to its use … the whole Western seaboard of Europe from the North Cape to the Spanish frontier in German hands; all the ports, all the airfields on this immense front, employed against us as potential springboards of invasion.”

“This grim talk did not dismay the British people. Instead, it braced them,” Ricks writes.

Orwell, poverty and power

Orwell, though he struggled at times to pay for food and rent, never wrote with an eye toward a paycheck. In his 1933 memoir “Down and Out in Paris and London,” he recounted living in near-destitution in both cities. His 1937 book “The Road to Wigan Pier” was a devastating look at poverty among the miners of northern England. “Homage to Catalonia,” Orwell’s 1938 account of fighting in the Republican army that defended Spain against Franco’s rebels, is pure heartbreak. It tells how Orwell’s comrades in a leftist militia were sold out by Soviet intelligence, who decided that the group was too Trotskyist and ordered its liquidation. Orwell’s friends died, then disappeared — the NKVD, Stalin’s secret police, built a special crematorium in Barcelona to dispose of the bodies. A marked man, Orwell fled.

It was a grim theater of events, and it shaped Orwell’s later novels. “Animal Farm,” a tale of power-hungry pigs who take over a farm after the human farmer flees, was such a devastating sendup of Soviet politics, Orwell had a hard time finding a publisher in left-leaning London. His dystopian classic “1984” predicated the rise of the all-seeing state.

“His literary method was to discover the facts and lay them out,” Ricks writes. “His perspective was that the powerful would almost always try to obscure the truth.”

Orwell's perspective was that the powerful would almost always try to obscure the truth.

Two lasting legacies

Both men experienced the inevitable decline of illness and loss, but Churchill won the

Ricks doesn’t try to make connections where none exist — the men lived parallel but separate lives. However, the last article Orwell published before his death in 1950 was a review of the second volume of Churchill’s war memoirs. His main character in “1984,” a man whose abiding desire was to live free, was named Winston.

Both Churchill and Orwell alerted the world to the clear and present danger of authoritarianism in all its forms. “Totalitarianism demands, in fact, the continuous alteration of the past, and in the long run probably demands a disbelief in the very existence of objective truth,” wrote Orwell in 1946. Readers of this book will realize, if they needed reminding, that the struggle to preserve and tell the truth is a very long game.

Gwinn, the former book editor of the Seattle Times, writes about books and authors for several publications and is on the board of the National Book Critics Circle.

“Churchill & Orwell: The Fight for Freedom”

Thomas E. Ricks

Penguin Press: 352 pp., $28

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.