The women who wielded a pen like a weapon: Michelle Dean’s ‘Sharp’

In the 1987 movie “Broadcast News,” a male colleague, angry at having to admit that Holly Hunter’s character, a television producer, is right about something, shoots this line at her: “It must be nice to always believe you know better, to always think you’re the smartest person in the room.” Hunter responds, huskily and urgently, a tear forming in her eye, “No, it’s awful.”

It’s a scene pretty much every woman I know holds dear; a little moment of truth that resonates with women in media and journalism especially, but one that any woman whose intelligence has been used as evidence against her will recognize. The dedication of Michelle Dean’s timely new book “Sharp” — “For every person who’s ever been told, ‘you’re too smart for your own good’” — could easily have been written for Hunter’s character, and for all the women (and some men, I guess) who identify with her.

“Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion” is a group biography of sorts, tracing a dozen female writers — from Dorothy Parker to Janet Malcolm — whose reviews, essays and other works compose a rough history of American thought from the 1920s to the ’80s.

“The forward march of American literature is usually chronicled by way of its male novelists,” Dean points out. “There is little sense, in that version of the story, that women writers of those eras were doing much worth remembering.” Dean, a contributing editor at the New Republic, is herself a gifted critic — her book reviews are often wickedly funny — and the women she writes about here are best known as critics, journalists and essayists (although some also wrote fiction or poetry). Besides Parker and Malcolm, they include Susan Sontag, Rebecca West, Zora Neale Hurston, Hannah Arendt, Mary McCarthy, Lillian Hellman, Pauline Kael, Joan Didion, Nora Ephron and Renata Adler.

Dean deftly and often elegantly traces these women’s arguments about race, politics and gender, making a kind of narrative of the ideas at play in the pages of the New Yorker, Vanity Fair, the New York Review of Books, the Partisan Review and other publications. Along with their male colleagues and competitors, these women wrote about books and movies, wars and revolutions, culture and society; their work pondered the meaning of the Holocaust, the prospects of the civil rights movement, the complications of making art in a world often riven with brutality.

But as Dean makes clear, these women lived different lives than the men they were published alongside. Their gender made them vulnerable to harassment and professional underestimation. Love, marriage and children complicated things (though they could provide good material, as in the case of Ephron using her divorce from philandering Carl Bernstein as the basis for her novel and film “Heartburn”) — and their looks and sexual lives became a topic of conversation in a way that male writers seldom encountered. “It is difficult to overstate how much writing about Sontag is concerned with her appearance,” Dean notes. “Even in the most serious essays about her there is usually some remark about her looks.”

Some of their male counterparts were friends, lovers and supporters — Edmund Wilson seems to have had a connection with nearly every woman in the book — while others appear as dirty old men or just plain hecklers (as when Norman Mailer, apparently blind to irony, panned McCarthy’s “The Group” as a failure due to the author’s vanity).

All of these women confronted sexism, both individual and institutional. But their attitudes toward feminism varied, as did their place in its history. British writer West worked to win votes for women, but, Dean writes, “found the suffragettes both admirably ferocious and unforgivably prudish.” Sontag, Ephron and Malcolm all wrote critically of second-wave feminism. Many of them attacked one another in print on issues of feminism but also aesthetic differences — notably, Adler’s savaging of Kael’s film criticism. But there is also genuine connection among many of these women — Malcolm’s note of appreciation to a dying Sontag strikes a note of grace and respect, as does Arendt’s tender treatment of a young Adler.

Feminism can be more than merely a political stance; as Dean examines the art of criticism plied by these writers, she identifies those whose approach to social and cultural events took on a more human, personal cast. In answering Isaiah Berlin, Diana Trilling and others who slammed McCarthy for what they saw as political unorthodoxy, Dean admits that “McCarthy was not a thinker of the type of John Stuart Mill, or Berlin himself. She did not spend her time articulating a full system of rights, or expound on the nature of justice. But insight into humanity is still a valuable skill for political analysis.” Later, still regarding McCarthy, she adds, “[i]deas were all fine and good, but they were lived out in the world, and were tethered to the humanity of those who had them.”

Dean’s prose is mostly plainspoken, and often persuasive. The book is consistently entertaining and often truly provocative — especially for anyone who makes or loves art or literature. Not every figure in it is equally compelling of course; some seem simply unlikable, but that too is a feminist stance (how many unlikable literary men do we read about?).

One complaint is inevitable: Because these women wrote for mainstream and highbrow publications in midcentury America, they are mostly all white (with the exception of Hurston, whom I wanted more of). It would have been nice to see Dean include more critics of color, but the world she’s writing about was even less diverse than publishing and journalism are now (and they’re still overwhelmingly white). There are other women I wish Dean had written about: Elizabeth Hardwick (who is one degree of separation from nearly everyone), Jessica Mitford, Joan Acocella, Ellen Willis, Margo Jefferson. What I really want to read next is a book about the diverse young critics — black, brown, queer, disabled — who are publishing now.

But that’s not to diminish this book, which feels urgent in its own right. “I gathered the women in this book under the sign of a compliment that every one of them received in their lives: they were called sharp,” Dean writes in the book’s preface. The word isn’t always complimentary. It implies intelligence and perception, but also danger and even violence, as in the blade of a knife. All of these women could wield a pen like a weapon, and one of the book’s most delicious pleasures is in reading about battles between critics. These days, book reviewers tend to avoid negativity or controversy — whether because we fear being ostracized on social media or worry about losing future freelance assignments. But the women Dean profiles here were willing to be unpopular. That made them not only sharp, but brave.

Tuttle is president of the National Book Critics Circle. She writes a weekly column on books for the Boston Globe and her reviews, essays and profiles have been published widely.

“Sharp: The Women Who Made an Art of Having an Opinion”

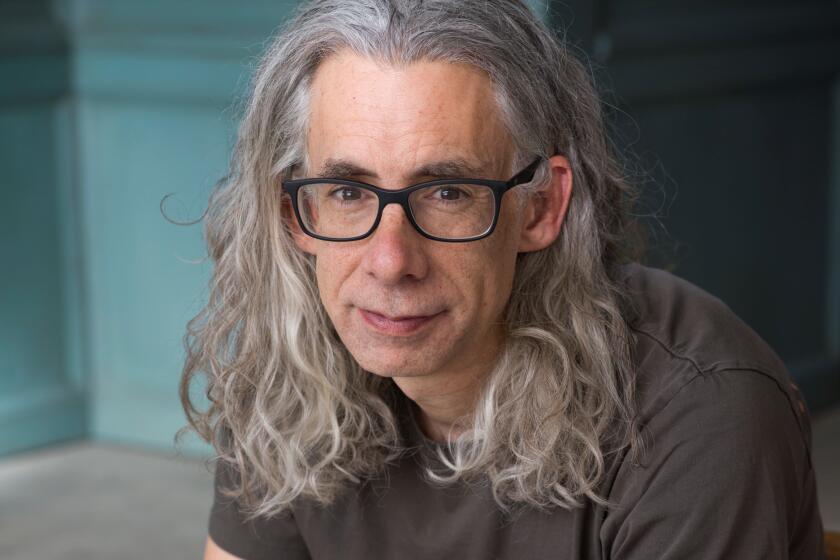

Michelle Dean

Grove Press: 384 pp, $26

Michelle Dean will be at the Festival of Books on Sunday, April 22, at noon on the panel “Badass Women Changing Culture” with Viv Albertine, Carina Chocano and Joy Press.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.