‘Mega-miracle’ will be needed to overcome dry February in Los Angeles

February is normally the wettest month of the year in downtown Los Angeles, when 3.8 inches of rain would usually fall. This year, next to nothing has fallen.

L.A.’s rainfall to date has been 4.39 inches, less than half of normal for this point, which is 9.71 inches.

In January, normally the second-wettest month, when L.A. should expect to receive 3.12 inches, only 2.44 inches fell. That makes January the wettest month so far this winter.

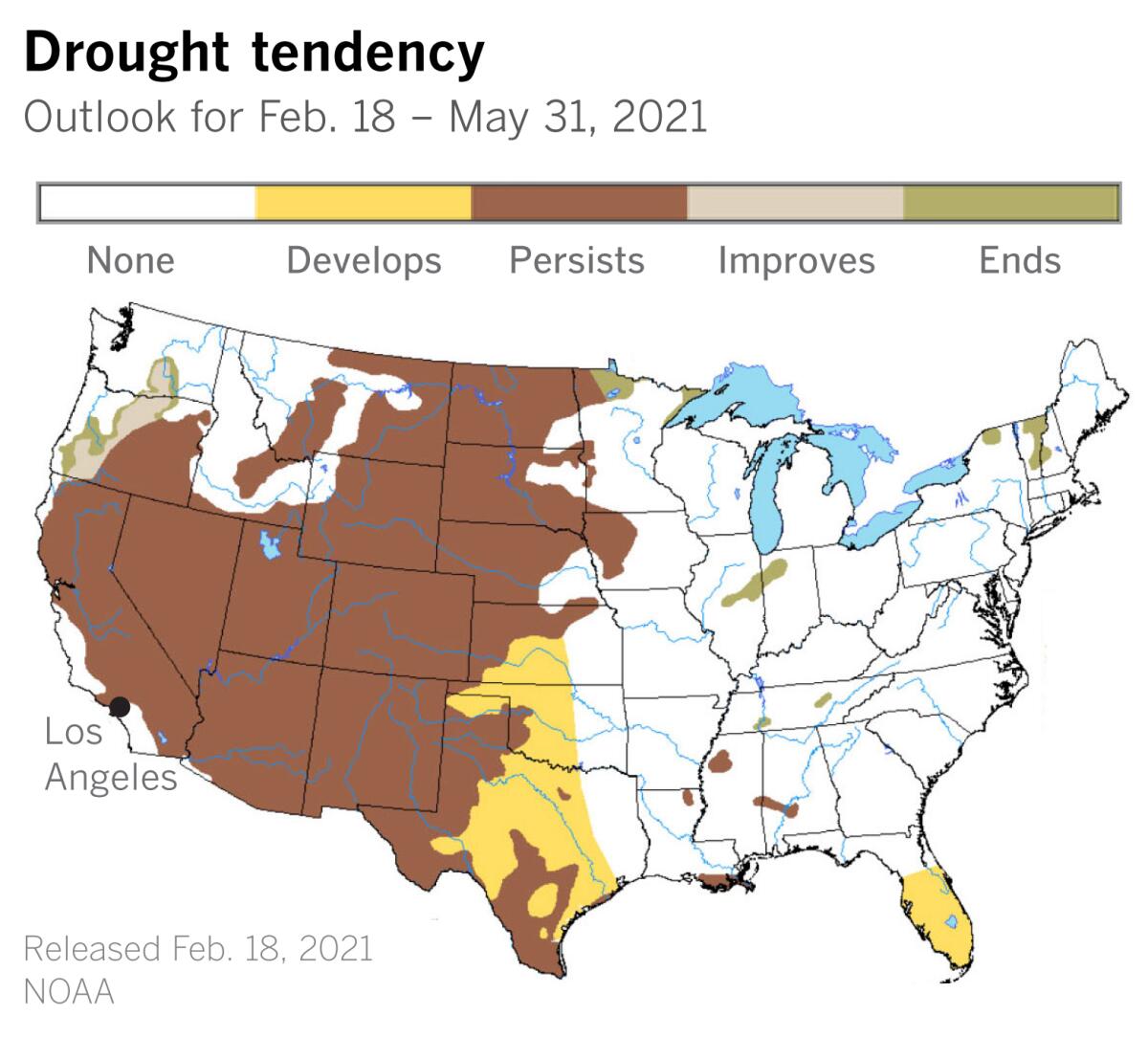

The outlook favors below-normal precipitation through the end of this month and, as climate scientist Daniel Swain writes, there is at least a chance that some areas of Southern California could see a complete February shutout.

“Except for one cool storm followed by a sweet atmospheric river in late January,” said climatologist Bill Patzert, “we’re coming out much like we did last year when our rainfall tally was a double-bagel in January and February.”

Last year in L.A., the months of January and February were dry, then the skies opened up during March and April, bringing rainfall to about normal in Los Angeles. It was a March-April miracle in Southern California, even as Northern California remained mostly dry.

But this year, Patzert says, “a March miracle is a long shot as long as the La Niña persists. We’re past the heaviest rainfall of winter.” We’re on the other side of the peak of the wettest months in a below-normal winter and, he adds, “it will take not a miracle, but a mega-miracle to get us to a normal rain year, which is 14.93 inches.”

A La Niña occurs when the sea surface temperatures in the central and eastern equatorial Pacific are below average. Easterly winds over that region strengthen, and rainfall usually decreases over the central and eastern tropical Pacific and increases over the western Pacific, Indonesia and the Philippines.

A La Niña pattern favors warmer, drier conditions across the southern tier of the U.S. and cooler, wetter conditions in the north.

The winter thus far has been pretty much as long-range forecasters predicted, Patzert says. “This is all very typical of a La Niña,” with a dry winter in the Southwest and a cold, stormy winter in the northern part of the country. Even the polar vortex this winter, which was extreme, typifies what Patzert calls “a lazy or meandering jet stream.”

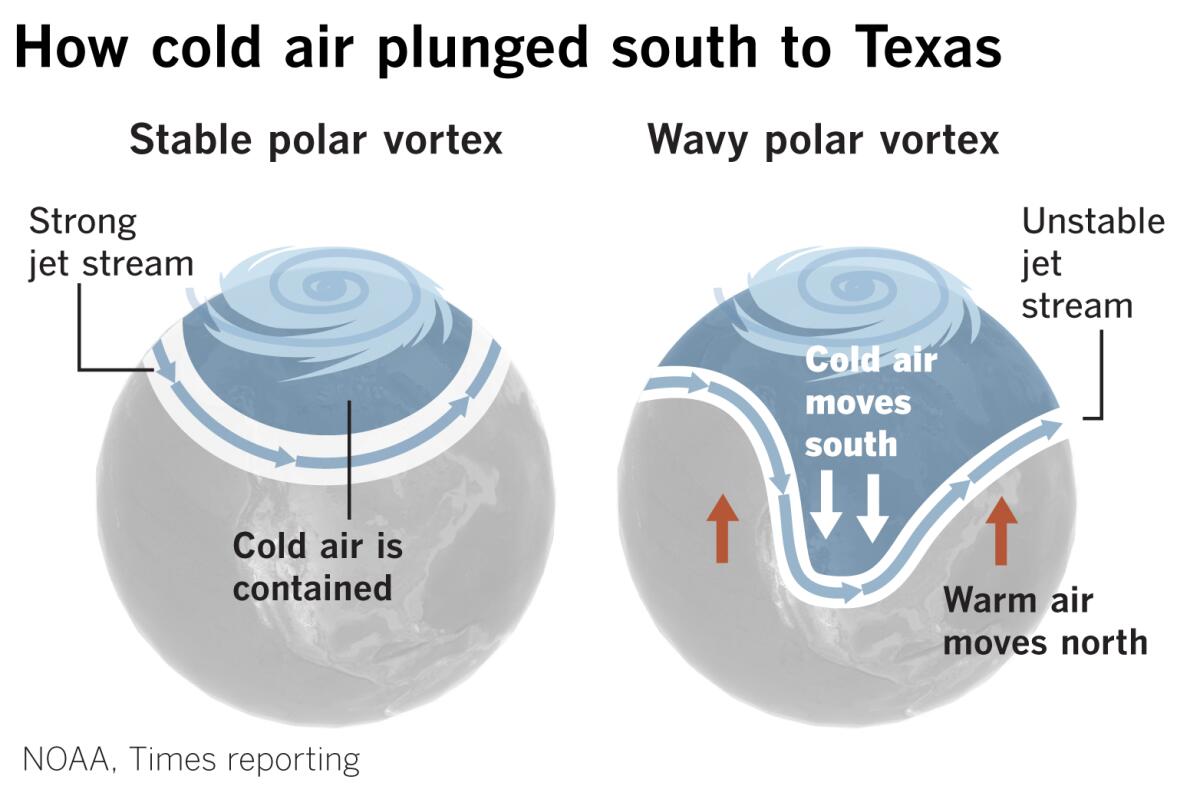

A strong polar jet stream girds the globe at higher latitudes, corralling the coldest Arctic air to the north. A weak or unstable jet stream is like a worn-out elastic band that can sag southward, allowing frigid air to wreak havoc, as was the case this week in Texas.

The big-picture pattern that has been keeping Southern California dry this winter involves summer-like high pressure lingering along the West Coast, blocking the storm track and keeping rain to the north. Low pressure in the Gulf of Alaska or over the Aleutian Islands has been weak.

The outlook calls for a ridge of high pressure to build into the Gulf of Alaska in the coming weeks. As Swain writes, this will favor relatively cool, dry northerly or northwesterly flow, with weak cold systems brushing Northern California, bringing coastal showers and some mountain snow. The precipitation will be below-average in Northern California, with even less in the southern part of the state.

The pattern also suggests windy conditions, with multiple “inside slider” systems creating strong surface pressure gradients, Swain says.

Inside sliders are low-pressure systems that move down from the north over land, riding the eastern side of the high-pressure ridge, often traveling over the Great Basin east of the Sierra Nevada. Unlike low-pressure systems that come down along the coast or over the Pacific Ocean — when the high-pressure ridge is weaker or standing off farther to the west — these lows are dry, and can produce a lot of wind, but generally little in the way of precipitation.

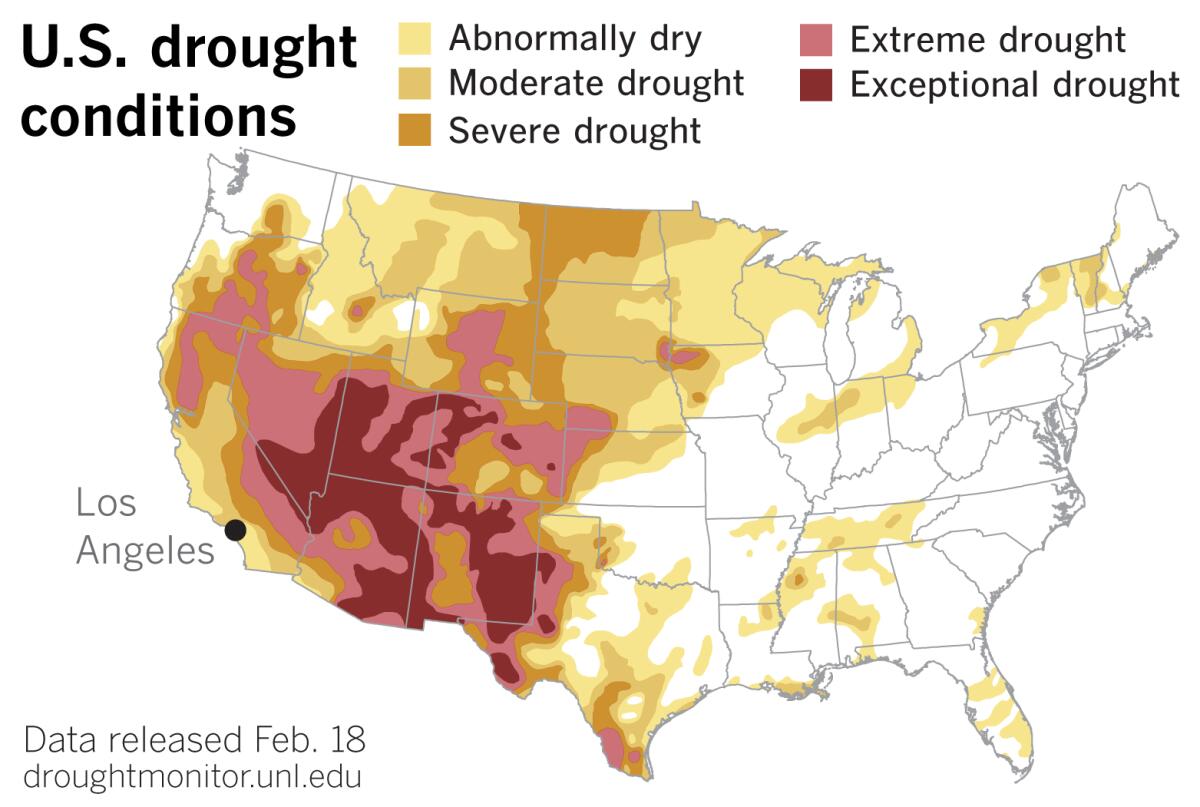

This isn’t good news for a dry, thirsty Southwest, where the monsoon was a no-show last summer, and for the Golden State, which just experienced its worst fire season on record.

According to the National Weather Service, the models show essentially no chance of rain through the end of February.

Los Angeles has received 45% of its normal rainfall to date. San Diego has tallied slightly less at 44%; Riverside has gotten 38%; Irvine is at 37%; Long Beach and Burbank stand at 36%; Palmdale is at 32%; and Palm Springs is at 22%. Imperial, with just a trace this season, has received 0% of its normal rainfall. (A trace means precipitation that was observed but was not enough to be measurable.)

To the north, in the Bay Area, San Francisco, Oakland and Livermore have gotten 43% of normal for the season. San Jose has gotten 41%, and Santa Rosa has gotten 40%.

Las Vegas has received only a quarter of an inch of rain (12% of normal) this winter, and Phoenix has gotten 31% of normal.

In L.A., after February and January, March is the third-wettest month, when 2.43 inches of rain would ordinarily fall. But if March is a docile lamb instead of a roaring lion, Los Angeles finds itself in a deep, dry rainfall hole. Opportunities for precipitation fall off rapidly after that. Less than an inch normally falls in April, and only about a quarter-inch typically falls in May.

This has serious implications for what is now a year-round fire season.

“All this is very ominous, given the string of below-normal rain years in the past decade, the immense drought footprint in the West and last year’s off-the-charts fire season,” Patzert said.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.