Californians will vote multiple times in 2022 for the same U.S. Senate seat

Concerns over the constitutionality of California’s long-standing law regarding vacant seats in the U.S. Senate will result in a potentially confusing one-time solution next year: side-by-side races, on both the statewide primary and general election ballots, for the same job.

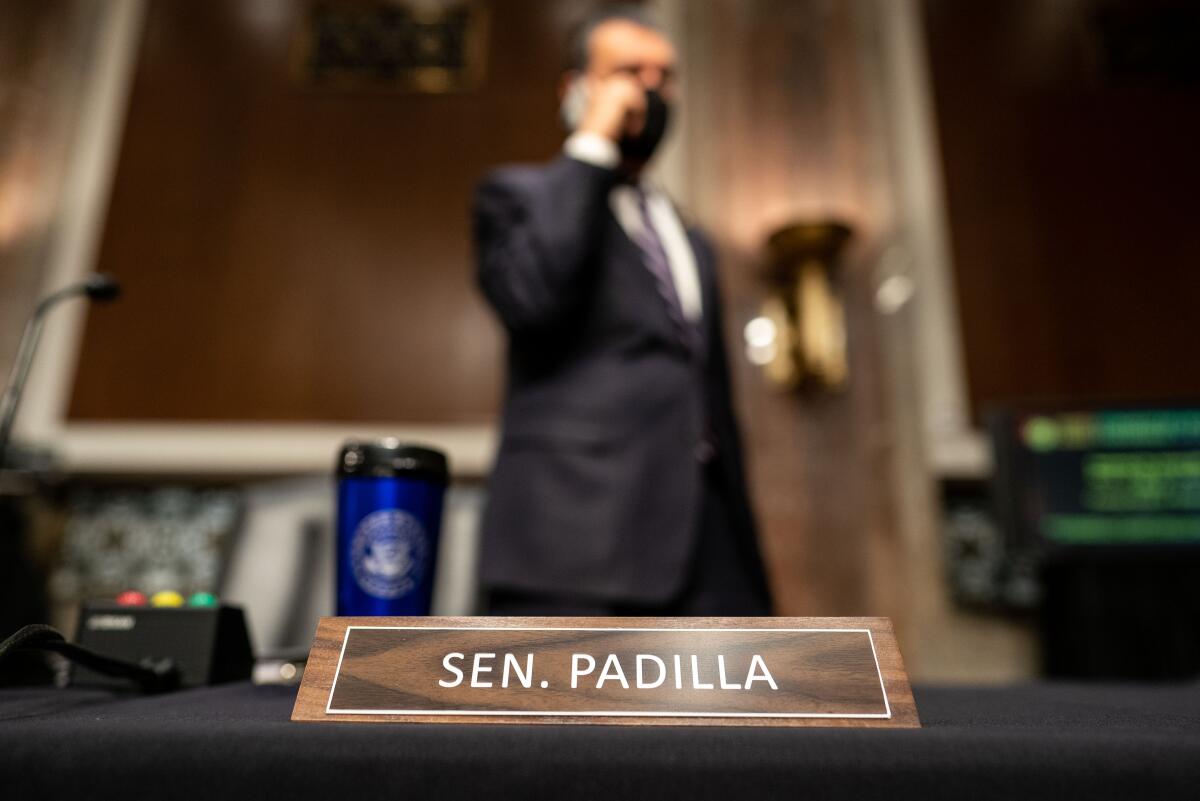

The change, signed into law Monday by Gov. Gavin Newsom, will have the most immediate impact on the political efforts of Sen. Alex Padilla, appointed by Newsom after Vice President Kamala Harris left her Senate post to take the nation’s second-highest-ranking job in January.

For the record:

10:23 a.m. Sept. 30, 2021An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that Republican Sen. John Seymour lost his bid for a new six-year term in 1992 to Democrat Dianne Feinstein and that a special election called to be held concurrently with the 1992 election was for a Senate term that was supposed to last until 1996.

Seymour lost his bid to Feinstein in 1992 to remain in office to finish an existing term, which ended in January 1995.

Padilla, who is seeking a full six-year Senate term in 2022, will now have to run in concurrent elections to continue serving the remainder of Harris’ stint. Voters will see two races — a special Senate election and the regularly scheduled one — next to each other on the ballot in June and then again in November.

Lawmakers pointed to a pair of federal court rulings in cases involving Illinois and Arizona, each suggesting California’s long-used method of filling Senate vacancies could be found illegal under the 17th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

The law signed by Newsom, Assembly Bill 1495, requires the governor to call two elections to fill a Senate seat — contests held in conjunction with the next regularly scheduled primary and general elections. If no election is scheduled before the unused time in office comes to an end, the governor could call a special election to fill the vacancy.

Prior to Harris’ resignation and Padilla’s appointment, a Senate vacancy in the middle of an elected term had not happened in California since 1991, when newly elected Gov. Pete Wilson appointed Republican John Seymour to fill the remaining two years on Wilson’s Senate term. Seymour lost his bid to remain in office in 1992 to Democrat Dianne Feinstein.

In Seymour’s case, Wilson called a special election to be held concurrently with the 1992 election, even though the Senate term was supposed to last through 1994.

The U.S. constitutional amendment in question was enacted in 1913 and abolished the practice of senators being appointed by state legislatures. The recent federal court rulings, according to a California bill analysis, cast doubt on lengthy appointments by a governor and affirmed the constitutional provision calling for an “election to fill such vacancies.”

Harris was elected to the Senate in 2016 for a six-year term that expires on Jan. 3, 2023. Under the law signed by Newsom, Padilla must stand for election to serve out those months while also vying for his own six-year term in the job.

“AB 1495 ensures that California law is consistent with the 17th Amendment,” Assemblyman Marc Berman (D-Palo Alto), chairman of the Assembly Elections and Redistricting Committee, said during a legislative floor debate in May.

Berman also noted that consolidating Senate vacancy elections with regular election cycles would “ensure the greatest participation in those elections” while avoiding the cost of holding special elections in all 58 counties.

Even so, there is a chance voters won’t easily understand what’s happening in June’s statewide primary. They will see two races for the same seat on the ballot, potentially with a mix of the same or different candidates. Padilla’s name will appear twice, as he seeks to finish Harris’ term and then begin a new one.

Assemblyman Kevin Kiley (R-Rocklin), an unsuccessful candidate in the gubernatorial recall, was an early critic of Newsom’s decision to not schedule an election to replace Harris. But he was critical of AB 1495 as it made its way through the Legislature, arguing that the bill gives the governor too much latitude to decide when Senate vacancy elections can be held.

“In my view, the better approach would be to have an election as soon as possible, to restore California’s full allotment of elected United States senators,” Kiley said during legislative floor debate in May.

While Senate vacancies are rare, Kiley and other Republicans believe the issue could soon return should Feinstein — elected in a special contest — decide to step down before her current term ends in January 2025.

Newsom, facing scrutiny in March over his selection of Padilla and with the recall effort looming, promised to appoint a Black woman to the Senate if Feinstein retired. Hours after the governor’s comments, Feinstein sharply rejected the idea that she might have plans to leave the job.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.