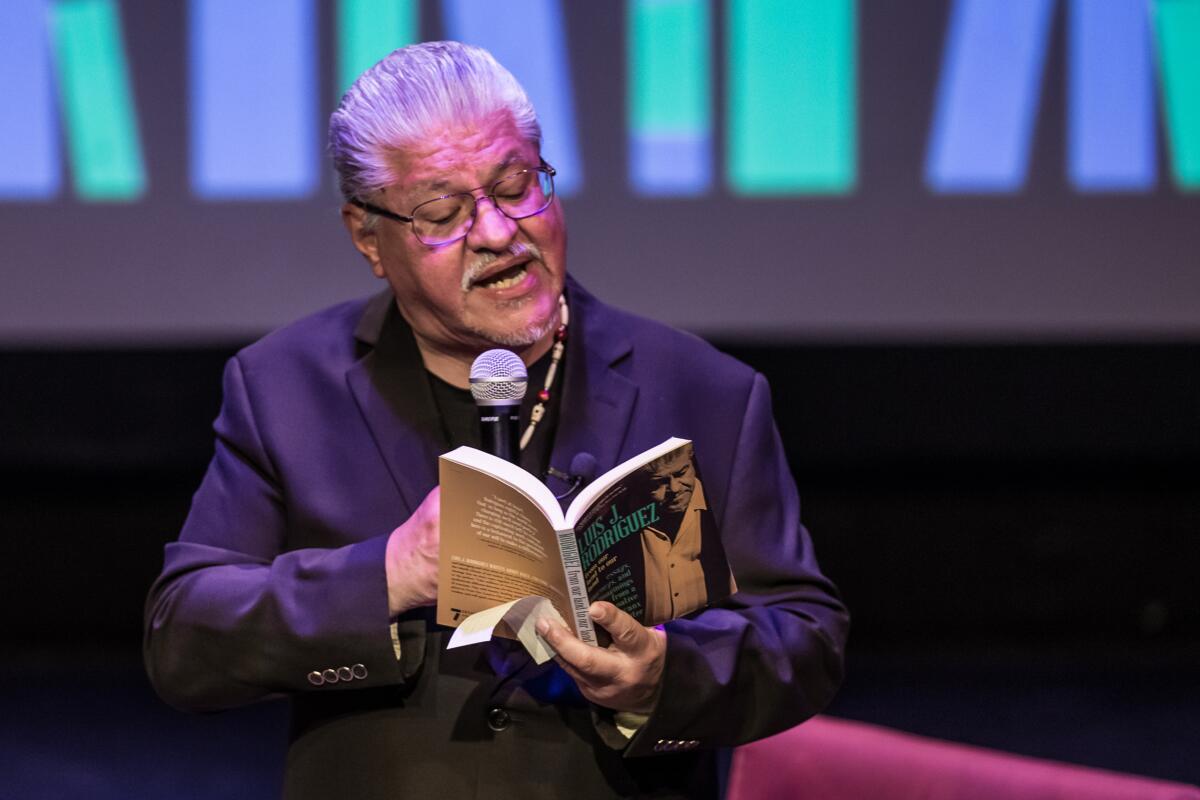

Luis J. Rodriguez on changing lives through poetry

Author and former Los Angeles poet laureate Luis J. Rodriguez says he’s been visiting California’s prisons for more than 40 years since leaving his own gang youth behind and losing 25 friends to drugs and street violence.

Lately, though, Rodriguez sees a difference when he goes behind bars to teach writing workshops. Once resistant, many prison administrators and correctional officers now welcome his presence — and encourage other education programs too.

“I have seen a lot of change. There were riots. There were lockdowns,” Rodriguez recalled of his prison visits in the ’80s. Now, “there’s artists. There’s musicians.”

“The violence has gone down. The drug use has gone down. It even makes their [prison staffers’] lives easier.”

In a wide-ranging conversation, Rodriguez spoke Saturday with the Los Angeles Times Book Club about his new story collection, “From Our Land to Our Land,” and his career using creative writing to explore identity and push for change.

Rodriguez first landed on the bestseller list with “Always Running,” his 1993 memoir about the gang years in Los Angeles that almost claimed his life. Since then he’s opened Tia Chucha’s, a community bookstore and cultural center, and written poetry, nonfiction, novels and children’s books. That body of work led to Rodriguez being selected to serve as L.A.’s poet laureate from 2014 to 2016.

He says he sees his work as a way of bringing people together in a divisive era, a theme that resonates throughout “From Our Land to Our Land.”

In an onstage interview with Times reporter Daniel Hernandez, Rodriguez talked about moving past the violence of his youth to work as a newspaper reporter, published author and community activist.

Rodriguez said he continues to visit prisons in California and around the world to serve as a mentor and teacher. He described the “buffed” men, their faces tattooed, sometimes 30 deep, waiting for him to come in.

“When we get to talking. When we get to writing ... these tough guys start feeling it,” Rodriguez told the audience at the Colony Theatre in Burbank. “The tears come down. It’s vulnerable. You can get killed for having those kinds of tears in places like that.”

In a previous life, you could never get Rodriguez to cry. He now sees that vulnerability is a form of strength. “Not enough men cry enough,” he said. “We lose so many women, so many kids to men who can’t feel.”

In his collection of essays, Rodriguez says everything, including identity, is up for reexamination. The author appends a note at the beginning, alerting readers that both “Chicano” and “Xicanx” terms find a home in his book.

“I’m not trying to be politically correct,” Rodriguez said. “We weren’t Latinos for very long either. That’s a new term too. We were Hispanics, and that wasn’t our term but for the longest time called Hispanics. People are coming up with all the things they want to call us. So this is an effort of us to call ourselves.”

Naming is not an abstract idea for Rodriguez, who received his third indigenous name: Mixcoatl Itzlacuiloh. He has it listed under his birth name in the book. “Among many indigenous communities, people would get new names every 13 years,” Rodriguez writes. “They were ‘born again’ not just once but many times.”

On Saturday, Rodriguez also dived into politics, expressing support for Democratic candidate Bernie Sanders, and discussed the controversy surrounding the Mexico-based novel “American Dirt” by Jeanine Cummins.

Rodriguez said he hasn’t read the novel, which some have complained is riddled with stereotypes and cultural appropriation. But Rodriguez didn’t mince words about the publishing industry. “I’ve yet to see the kind of money that they offered, that they gave Jeanine Cummins,” he said. “It’s only because she’s white. There’s no other reason to give someone more than a million dollars. They’ll never give it to Chicanos.”

The problem, Rodriguez says, is racism in the publishing and art world. “Collectors determine this, and the collectors aren’t us.”

Rodriguez wondered out loud why publishers don’t approach Latino writers and offer similar contracts for their stories. “They won’t do it.”

“If you’re going to write about other people, you better take a lot of responsibility,” he said. “We’ve been written about by others and the responsibility has not been there.” He then fired off the names of Latino authors, like Javier Zamora, Hector Tobar, and Claudia Rodriguez, as examples of those who have been writing their experiences authentically.

Saturday’s book club event also included a poetry performance by 18-year-old Jason Alvarez.

Alvarez is a member of Get Lit, a group of young spoken-word poets in Los Angeles. Until recently he didn’t know much about poetry. “I thought it was just about Shakespeare and Dr. Seuss,” Alvarez said, sitting in the front row next to his parents.

He performed “Mi Vida Loca,” an ode to his neighborhood in Northridge inspired by Rodriguez.

Alvarez recalled listening to Rodriguez read poetry at Tia Chucha’s Cultural Center. On Saturday Rodriguez was listening to him.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.