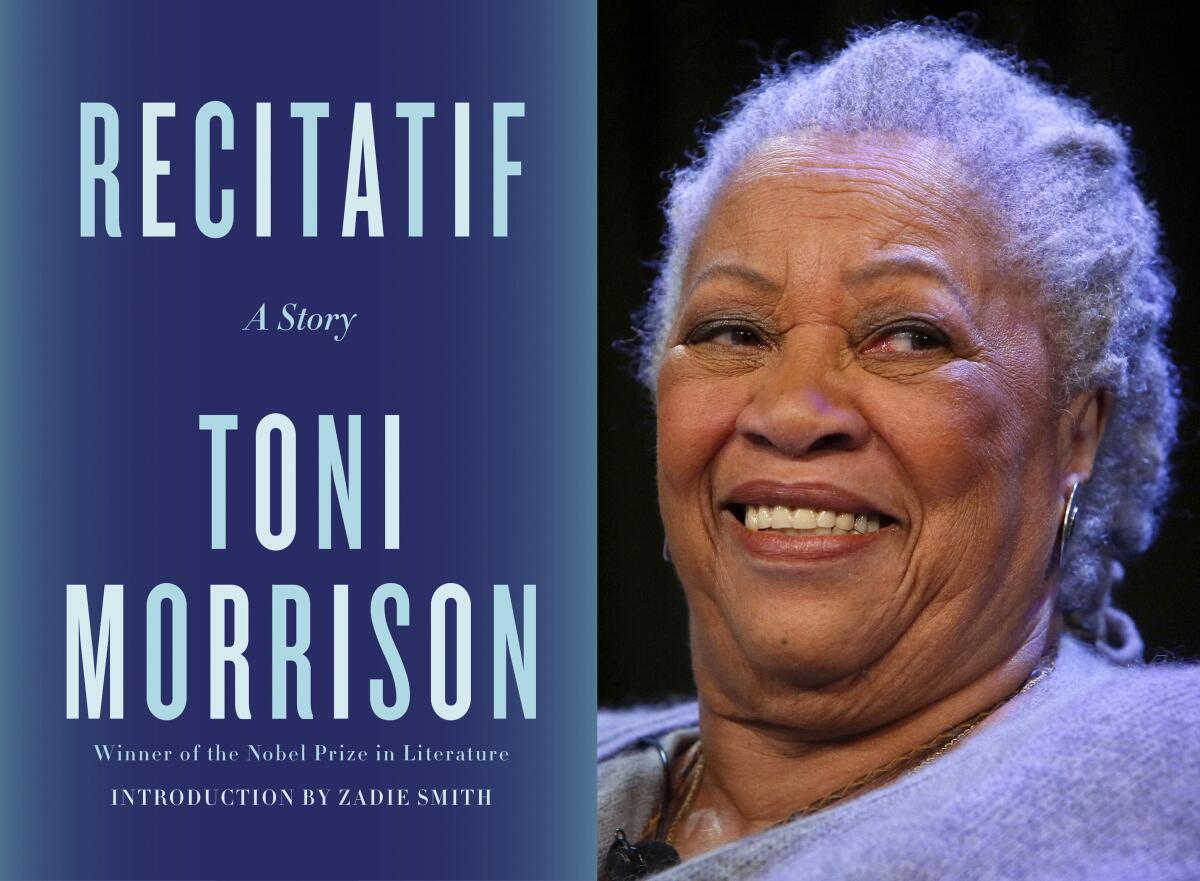

Rare Toni Morrison short story ‘Recitatif’ to be published as a book

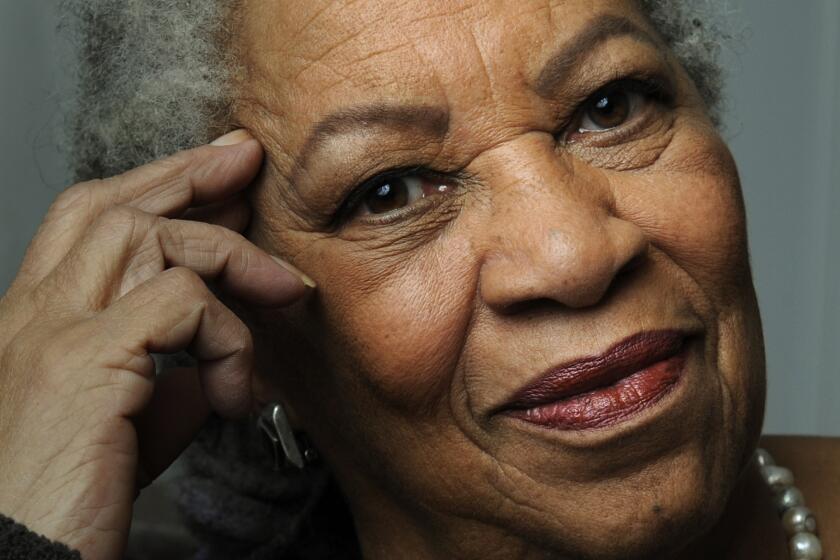

To much of the world, the late Toni Morrison was solely a novelist, celebrated for such classics as “Beloved,” “Song of Solomon” and “The Bluest Eye.”

But the Nobel laureate, who died in 2019, did not confine herself to one kind of writing.

Morrison also completed plays, poems, essays and short stories, one of which is coming out as a book Feb. 1. “Recitatif,” written by Morrison in the early 1980s and rarely seen over the following decades, follows the lives of two women from childhood to their contrasting fortunes as adults. Zadie Smith contributes an introduction, and the story’s audio edition is read by the actor Bahni Turpin.

According to Autumn M. Womack, a professor of English and African American Studies at Princeton, where Morrison taught for years, the author had written short fiction at least since her college years at Howard and Cornell universities, though she never published a story collection. “Recitatif” was included in the 1983 release “Confirmation: An Anthology of African American Women,” co-edited by the poet-playwright Amiri Baraka and now out of print.

“One of the main takeaways from it [‘Recitatif’] is that you’ll begin to think of her as someone who experimented with form. You’ll get away from the idea that she was solely a novelist and think of her as someone who was trying all kinds of writing,” Womack said.

“Recitatif” refers to a musical expression defined by Merriam-Webster as “a rhythmically free vocal style that imitates the natural inflections of speech,” a style Morrison’s often suggested. The story tells of a series of encounters between Roberta and Twyla, one of whom is Black, the other white, although we are left to guess which is which.

Toni Morrison, the author, essayist and winner of Nobel and Pulitzer prizes, famously encouraged would-be writers to take action.

They meet as girls at the St. Bonaventure children’s shelter (“It was something else to be stuck in a strange place with a girl from a whole other race,” recalls Twyla, the story’s narrator). And they run into each other on occasion years later, whether at a Howard Johnson’s in upstate New York, where Twyla works and Roberta comes in with a man scheduled to meet with Jimi Hendrix, or later at a nearby Food Emporium.

“Once, twelve years ago, we passed like strangers,” Twyla says. “A black girl and a white girl meeting in a Howard Johnson’s on the road and having nothing to say. One in a blue and white triangle waitress hat — the other with a male companion on her way to see Hendrix. Now we were behaving like sisters separated for much too long.”

As Womack notes, “Recitatif” includes themes found elsewhere in Morrison’s work, whether the complicated relationship between two women that was also at the heart of her novel “Sula” or the racial blurring Morrison used in “Paradise,” a 1998 novel in which Morrison refers to a white character within a Black community without making clear who it is. Morrison often spoke of race as an invention of society, once writing that “the realm of racial difference has been allowed an intellectual weight to which it has no claim.”

In her introduction, writer Smith likens “Recitatif” to a puzzle or a game, while warning that “Toni Morrison does not play.” The mystery begins with the opening lines: “My mother danced all night and Roberta’s was sick.”

PEN America asked the Colton school district to rescind its ban on Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” not realizing it had already done so.

“Well, now, what kind of mother tends to dance all night?” Smith writes. “A black one or a white one?” Throughout the story, Morrison will refer to everything from hair length to social status as if to challenge the reader’s own racial assumptions.

“Like most readers of ‘Recitatif,’ I found it impossible not to hunger to know who the other was, Twyla or Roberta,” Smith acknowledges. “Oh, I urgently wanted to have it straightened out. Wanted to sympathize warmly in one sure place, turn cold in the other. To feel for the somebody and dismiss the nobody.

“But this is precisely what Morrison deliberately and methodically will not allow me to do. It’s worth asking ourselves why.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.