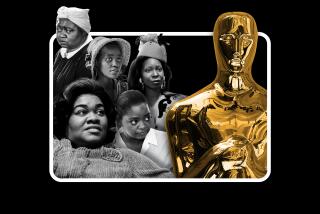

Q&A: Marlee Matlin remains a champion for disabled actors, 30 years after winning her Oscar

When Marlee Matlin was a teenager, she didn’t care about the Academy Awards. She never watched the ceremony, opting for Miss America or reading Tiger Beat magazine.

But after being cast in a stage production of “Children of a Lesser God” at 19 and winning the lead actress Oscar for that same role in 1987, her eyes were opened to “a new world” of trade magazines, film criticism and Hollywood hobnobbing. The deaf actress’ history-making win, as the first — and still only — disabled actor to be recognized, catapulted her into notoriety and fame.

For the record:

2:08 p.m. Aug. 18, 2019An earlier version of the story stated that Marlee Matlin was the first disabled actor to win an Academy Award. In 1946, Harold Russell, a World War II veteran who lost his hands due to a training accident, won the supporting-actor Oscar and a special award for his role in “The Best Years of Our Lives.”

Thirty years later, however, as Hollywood continues to grapple with diversity and inclusion on the heels of #OscarsSoWhite, industry opportunity for disabled actors is still too far and in between.

“Diversity is a beautiful, absolutely wonderful thing, but I don’t think they consider people with disabilities and deaf and hard of hearing people as part of the diversity mandate,” said Matlin, 51. “We have people of all diverse backgrounds in incredible work this year with mind-blowing performances, but we actors who are deaf — and I’m not complaining [because] we should write ourselves and act ourselves and create ourselves. But it doesn’t seem that the mainstream is still willing to accept it.”

Full coverage of the 2017 Academy Awards »

Matlin has spent the last three decades beating the drum for disabled actors. Through her example — with notable roles on “Reasonable Doubts,” “Law & Order: Special Victims Unit” and “Switched at Birth” — she has shown that having different abilities doesn’t automatically preclude someone from working in the industry. She even has a voice-over agent, prompted by a recurring role on “Family Guy.” (“Isn’t that cool? I have a voice-over agent,” she said.) The Ruderman Family Foundation, an internationally recognized organization that advocates for people with disabilities, honored her with its Morton E. Ruderman Award in Inclusion this year.

On the anniversary of her win, The Times spoke with Matlin, and her longtime interpreter Jack Jason, about receiving the Oscar 30 years ago, its impact on her career and the state of opportunity for other differently-abled actors.

How did you get the chance to audition for the lead in “Children of a Lesser God”?

I was doing a local production in Chicago of the play [that the movie is based on]. I was the supporting role of Lydia. The opening night, there was a casting director from Paramount in the audience. They had been looking for the lead of the film for three or four years and hadn’t been able to find anybody. She met all of us, and then the next day we were asked to videotape ourselves in our roles [as an audition]. According to Randa Haines, who was the director of the movie, she saw me in the background and said, “Who is that? Let me see her in the lead role.” It was a very intense process of auditioning for this, because I was only 19 and I had no experience in television or film, or anything having to do with Hollywood. I was very, very naïve and an outsider.

Do you remember the call saying you got the job?

I was at my mom’s house and a call came in from my agent, through what we called Teletypes. It was 11 in the morning and my agent had a question: “Would you be willing to do a nude scene?” [I said, “Yes.”] Three minutes later, she called back and she said, “Congratulations.” I just sat there and thought, “Oh my goodness.” Then my mother was standing in the doorway, crying, with her phone book ready in hand to call everybody that she knew.

Describe for me the emotions you had once your role began garnering critical attention and eventually the Oscar nomination?

There was no social media at that time so all of it came through the telephone or telegrams or snail mail or word-of-mouth. It was overwhelming for me because [of] the love, the support and even the hating on the part of some people who felt I hadn’t paid my dues. I was just a young girl from Northbrook, Ill., and I was thrust into the spotlight of Hollywood. So much was going on that I had to grow up very, very fast, which was good and bad.

You won your first time out of the gate.

I had no prepared speech. No one told me you could do a prepared speech. But it was a very proud moment for me [because of] the accolades and support that I received, particularly from deaf people.

On the next day, I got reviewed. Most of them [were] positive until one particular column by Rex Reed said that my win the night before was probably the result of a pity vote and that he thought that I wasn’t necessarily the one who deserved the Oscar because I was a person who was deaf, playing a person who was deaf. And how was that acting? [Rolls her eyes.] Before I could even react, there was an article that said I was great but I’ll never work again because I was deaf and I don’t speak. So they defined who I was. That was disappointing to me, but I put that all aside and I continued to celebrate my uniqueness and looked forward to whatever was next.

[Editor’s note: Though no disabled actor has won an Academy Award since Matlin in 1986, in 1946 Harold Russell, a World War II veteran who lost both hands due to a training accident, earned two Oscars for his role in “The Best Years of Our Lives.”]

Did the Oscar make you a bona fide, working actress?

It wasn’t as if it was happening as quickly as I would have thought. There might be something, and then there’d be a wait, then somebody might do something and then they’d wait another while. It happened slowly but surely. We decided, if we’re going to have to wait, to do television. I did not have really an option of choosing work or what path I would take, theater or film or television. I realized that very quickly. When I asked people why it was this way, they said it was because I was deaf. I said: “That’s bull … .”

Thirty years later, you’re still the only winner with a disability. What is the state of opportunities out there for actors who happen to be deaf?

There are an amazing number of disabled actors out there, and not only in the United States. Even though 20% of the population has a disability, 2% of roles [in Hollywood are for disabled characters] and of that 2%, only 5% are played by people with disabilities. The rest are played [by actors without disabilities]. Casting directors, I wish they would really understand the importance of acknowledging real diversity. Even though people know who I am, it doesn’t mean that I get scripts every day. And the answer’s always been, “We don’t know how to write for you. We don’t want to see subtitles if you happen to be signing. We don’t want the audience to be uncomfortable with the voice.” They find reasons not to [hire me].

10 leading performances and 10 key scenes that could help these nominees take home the Oscar »

Is there anyone doing diversity properly in your eyes?

“Switched at Birth” did it so well. They included all kinds of deaf actors in the show, and that’s what diversity is about. We did an episode where it was all done in American Sign Language. It had never been done in the history of television. [Creator] Lizzy Weiss really was fearless in going forward as was the rest of the production team. We told 103 stories and it was amazing ... I want to see more. It’s an honor to get an award, but it’s a greater honor to keep on working. There are some people who get it, like Aaron Sorkin or Ilene Chaiken or David Kelley.

We’re not going to sit and wait. We have to develop ourselves, and if it means on Seeso or Hulu or Amazon, why not?

I’m not trying to put these people down who don’t get it. It’s just ... if you want authenticity, and you want authentic stories, and it happens to have deaf people in it, hire deaf people and you’ll have a story to tell.

Get your life! Follow me on Twitter (@TrevellAnderson) or email me: trevell.anderson@latimes.com.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.