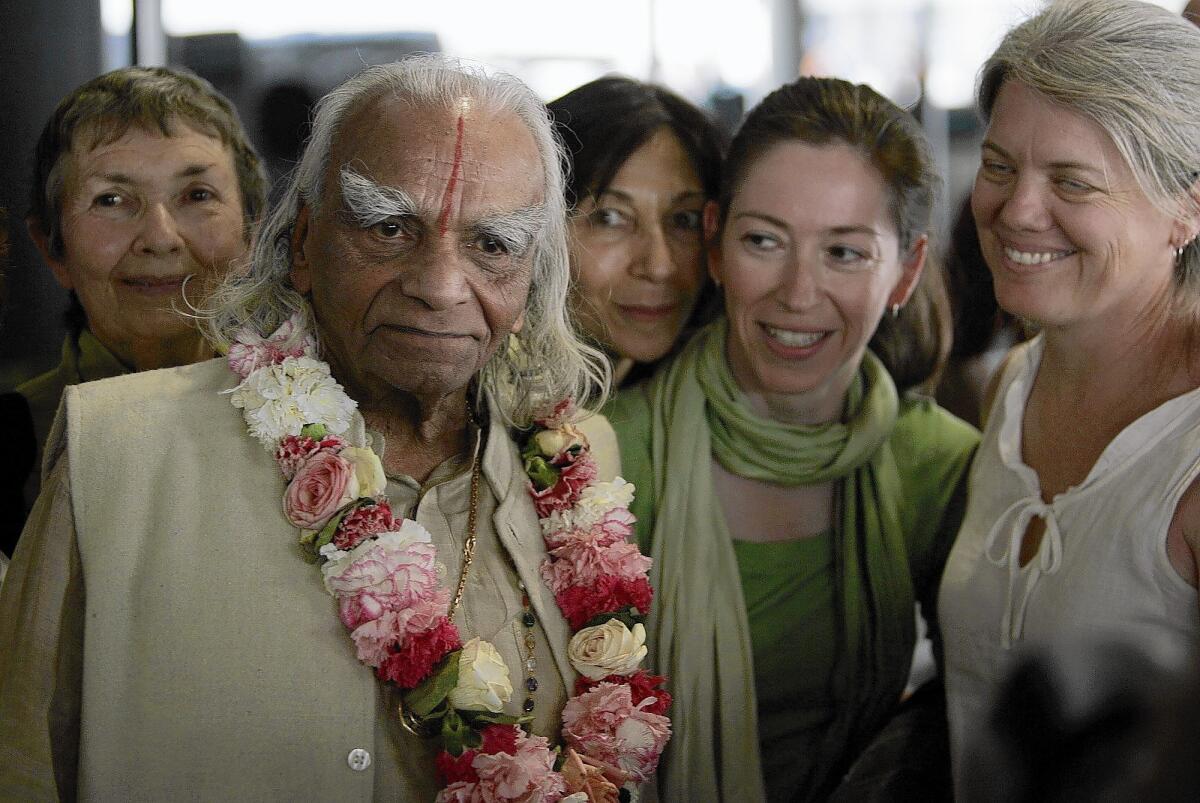

B.K.S. Iyengar dies at 95; Indian guru helped popularize yoga in West

Before he became one of the West’s most influential teachers of yoga, B.K.S. Iyengar was a frail baby in a poor family in India. Born in 1918 during a worldwide flu epidemic, he survived infancy only to struggle with other deadly maladies, including malaria, typhoid and tuberculosis.

The illnesses left him a pathetic, bony-chested weakling for whom the future appeared dim.

“I was,” he quipped later, “an anti-advertisement for yoga.”

No one, including Iyengar, could have predicted what a difference a few years would make. The once-scrawny youth who was told he would not survive to adulthood began studying yoga at 14 and teaching at 18. He gradually built a reputation that spread to the West, where he helped lay the foundation for the explosive growth of yoga as practice and industry and attained rock-star status with tens of thousands of followers, including such celebrities as actresses Ali MacGraw and Annette Bening.

His seminal 1966 book, “Light on Yoga,” became a worldwide bestseller, with more than 1 million copies sold in 17 languages.

“No other individual has been as influential in turning yoga into a phenomenon that somehow retains the essence of its mystical aura while being continually made and remade in the image of a modern commodity,” Joseph Alter, a University of Pittsburgh anthropologist who has written widely on the history and development of yoga in the West, said Wednesday.

Iyengar was 95 at his death Wednesday in Pune, India, said officials of the Iyengar Yoga National Assn. of the United States, which promotes his teachings and certifies Iyengar instructors in the U.S. Iyengar, who was still doing extended headstands well into his 10th decade, had been hospitalized for heart and kidney problems.

When he began teaching in the 1930s, yoga was not just unfashionable, it was freakish. “I set off in yoga 70 years ago when ridicule, rejection and outright condemnation were the lot of a seeker through yoga even in its native land of India,” he wrote. “Indeed, if I had become a sadhu, a mendicant holy man, wandering the great trunk roads of British India, begging bowl in hand, I would have met with less derision and won more respect.”

Yoga has become a $10-billion industry, thanks to the more than 20 million Americans who practice yoga, according to a 2012 survey by Yoga Journal. About 2 million are Iyengar followers.

Experts say that the phenomenal growth of all forms of yoga is owed in large measure to the Iyengar founder.

“When we started 50 years ago I would tell people I taught yoga and they would think I said yogurt,” said Eric Small, a senior Iyengar instructor in Los Angeles who studied with the master for 50 years. “He made a very esoteric art that was sort of mysterious very practical and applicable to everybody.”

The ancient discipline of yoga became, in Iyengar’s hands, a form of physical therapy as much as a spiritual practice.

Guided by the principles of Patanjali yoga, Iyengar emphasized form and postures, called asanas, to realign weak areas of the body. He also introduced the use of props, such as belts, ropes, blankets and weights, which enabled him and other people with health problems to build strength and perform challenging exercises. Iyengar yoga gradually became recognized as a treatment for headaches, hypertension, arthritis and other medical conditions.

It was a demanding prescription for health, requiring persistence and sweat. His students found that his personal style was also intimidating: He was notoriously brusque and hands-on. Some students joked that his initials B.K.S. stood for beat, kick, slap.

Judith Hanson Lasater, a longtime Iyengar instructor and a founder of Yoga Journal, recalled the first time she studied with the master.

“In that first class, there was a man wearing a turban,” she said in an interview. “Mr. Iyengar looked at him and said, ‘Do you want to find God?’ and man said, ‘Oh, yes.’ Mr. Iyengar looked at him and said, ‘You don’t even know what your foot is doing.’”

He was born Bellur Krishnamachar Sundararaja Iyengar on Dec. 14, 1918, in Bangalore, India. The son of a teacher, he was one of 13 children.

His mother came down with the flu that wound up claiming millions of lives in 1918 and 1919. Plagued by sickness throughout his youth, Iyengar missed so much school that he failed his examinations and lost the chance to attend college. “I was a burden to myself and my family,” he said.

His luck changed when he began studying yoga with his brother-in-law, who thought him a dismal prospect: The teenager was so stiff he couldn’t touch his toes. But he soon was helping the older man give demonstrations. In 1936, he gave his first class to a group of women. When he was married in 1943, his wife, Ramamani, urged him to expand his efforts.

By 1952, word of the restorative effects of his teaching had spread beyond India. That year, Yehudi Menuhin, the American-born violinist and conductor, began to study with Iyengar and after a series of classes found that his concentration and playing had improved. He began to call Iyengar “my best violin teacher” and introduced the guru to other musicians and notables, including Belgium’s Queen Mother, who was 80 when she learned from Iyengar how to stand on her head.

“Once she’d done it, I taught her gardener to help her up,” Iyengar recalled in the Times of London in 2005.

In 1956, Iyengar came to the U.S., becoming one of the first yogis to teach in the West, along with other pioneers like Pattabhi Jois, one of the modern fathers of the ashtanga school of yoga.

His book “Light on Yoga,” with 300 pages of instructions and illustrations, became a revered text. By the early 1970s, Iyengar established an institute in Pune that eventually spawned hundreds of Iyengar centers around the world.

He traveled to the U.S. numerous times over the decades, including a 2005 visit to Los Angeles, when he held a seminar at UCLA. MacGraw emceed the event and Bening interviewed him before a standing-room-only crowd.

A year earlier, the word “Iyengar” was added to the Oxford English Dictionary.

At 90, Iyengar could head-stand for half an hour without shaking.

“I’m improving still, progressing still,” he told Yoga Journal in 2008. “That is why I am still practicing with such energy. The mortal body has its limitations. Therefore, I will still practice ‘til the last breath of my life so that I do not become a servant of the mind, but rather the master of the mind.

“Old age makes a strong man say goodbye. I am breaking the fear complex and living with confidence.”

His wife died in 1973. His survivors include five daughters, Geeta, Vanita, Suchita, Sunita and Savita; and a son, Prashant.

Times staff writer David Colker contributed to this report.

elaine.woo@latimes.com

Twitter: @ewooLATimes

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.