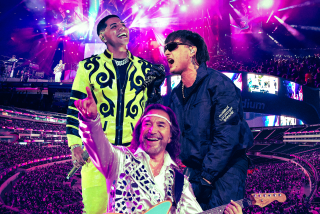

Último Guerrero is one of the biggest names in Mexican wrestling — a world-famous star known for his punishing moves, long black mullet and silver-capped front tooth.

He has toured Asia, South America and Europe, won dozens of championship belts and can’t walk down the street here without fans pestering him for autographs.

But in the months since the coronavirus struck and wrestling arenas were closed, the 48-year-old icon has been flipping burgers at a food truck.

“Everything stopped,” he said on a recent afternoon, a chef’s apron pulled tight over his bulging pectoral muscles, the smell of sizzling beef and onions wafting down the street outside his house in Mexico City. “Like everybody else, I had to do something to survive.”

Lucha libre — literally “free fight” — is its own religion in Mexico, and wrestlers are gods.

The pandemic has brought them down to earth.

Even the best-known wrestlers were never paid very well, earning about $1,000 a week, most of it from a cut of ticket sales.

With no matches save a few televised contests, superstars and up-and-comers alike have had to rely on emergency donations from fight promoters.

Many have also begun selling street food.

There is Olímpico, with his crepe stand, and Rey Bucanero, with his ice cream and waffles joint. Shocker, who opened a lucha-themed taco truck last year to help raise money for jaw surgery, now lives off it. Many lesser-known wrestlers have also reinvented themselves as street vendors, hawking tortas, carne asada and doughnuts.

For wrestlers looking for quick cash, street food makes sense.

It is informal, with no permits or rent required. And luchadores have a leg up when it comes to marketing, with built-in networks of fans.

Último Guerrero — who per custom only revealed his face and real name, José Gutiérrez Hernández, after defeat in a high-stakes fight six years ago forced him to remove his mask — opened the hamburger stand with his pro-wrestler wife, the yet-to-be-unmasked Lluvia.

In their working-class neighborhood on the northern edge of the city, street food is a way of life.

On one side of their house is a stand that sells pork ribs so juicy that lines often extend down the block. On the other, a chef who lost his job at a resort in Cancun because of the pandemic sells cochinita pibil in front of his mother’s home.

But the biggest draw now is the brightly painted truck, which features images of Último Guerrero and Lluvia, whose stage names translate to “Last Warrior” and “Rain.”

“People!” a friend shouted into a microphone, mimicking a wrestling match announcer. “We have hamburgers!”

The clientele includes neighbors, but also fans who come from afar to rub shoulders with their heroes.

“Enjoy!” Último Guerrero told a star-struck admirer after he posed for a photo in his signature blue-and-white wrestling mask and then handed over a plastic bag laden with cheeseburgers and fries.

“If it’s tasty, tell your friends,” the wrestler joked. “If it’s not, don’t tell anybody.”

The customer, Rene Núñez, giggled like a child. He and his wife had driven an hour and a half to be there.

“I’m a super fan,” said Núñez, 32, who before the pandemic used to attend at least two wrestling matches each month. He compared lucha to the theater — “except you get to drink beer and don’t have to stay in your seat.”

He gazed at Último Guerrero, who was now seasoning beef patties: “This is seeing your idol in flesh and blood.”

Lucha libre mixes athleticism, strength and cartoonish masculinity with tight Lycra pants and sparkly masks. Since the first league was founded nearly a century ago, it has been the sport of the working class, with both fans and performers generally coming from humble origins.

Último Guerrero grew up in the northern state of Durango, where his mother sold flour tortilla tacos known as gringas on the street. For the last three decades, he has awakened at dawn to train two hours at the gym and then wrestled nearly every night, sometimes performing in four different cities in a single week.

The last six months have felt like a vacation. The chronic pain in his shoulders has subsided, and he no longer takes painkillers. “My body doesn’t ache,” he said. “I feel good.”

He and his wife are having fewer arguments than when they both were wrestling. He now cooks for his family every morning, and then spends a few hours showing his 3-year-old son lucha moves.

In the ring, Último Guerrero played to the crowds and warned opponents: “If living is your destiny, you wouldn’t have crossed my path.”

Working the grill in the food truck, he is far less intimidating. “I like food and being with people,” he said.

In the months since the coronavirus struck and wrestling arenas were closed, many Mexican wrestlers rely on street food vending to make a living.

On a recent cool evening, a patrol car carrying municipal police stopped in front of his stand and an officer sauntered over.

“How’s business going?”

“Little by little,” the wrestler responded.

The officer told him to be alert for extortion threats, which he said were on the rise in the neighborhood, and handed him a business card.

“Right now there are guys asking businesses to pay 20 to 30 pesos a day,” the officer said. “If they come by, call us.”

As the officer walked away, one of the wrestlers’ friends snickered. It was ironic, the idea that one of the toughest guys in Mexico might need help protecting himself.

For other wrestlers, the pandemic has been a humbling experience.

Olímpico, a lean 54-year-old with a shiny bald head who often fights Último Guerrero, said years of battling under the bright arena lights had inflated his sense of self.

“We thought we were eternal,” he said. “We never knew something like this could happen.”

Parties are crucial to Mexican culture, binding family and community. The pandemic has put them on hold.

But this spring, as it became clear that matches would not resume for months, Olímpico began working with his wife at the small crepe stand she runs in Tepito, in Mexico City’s historic center, just a few blocks from where he grew up as Joel Bernal Galicia.

“She’s a very nice boss,” he said on a recent night as she poured batter onto a hot griddle and he spread a warm crepe with Nutella, fresh berries and whipped cream.

They exchange smiles. “She spoils me a lot.”

His wife, Leticia Vázquez Rojano, is glad to have the company.

In their eight years of marriage, his relentless schedule dominated their lives. He left the house early to train and came home late, exhausted and in pain.

“It’s a very stressful life,” he said. “If we weren’t in the gym, we felt guilty.”

“I lost my ego. I realized: I’m a person who also needs help, and I have a body that also needs rest.”

— Olímpico

With crepe sales not enough to pay the bills, the couple have also relied on charity donations.

“At first I thought, ‘How can Olímpico go and accept a handout?’” he said. “But then I lost my ego. I realized: I’m a person who also needs help, and I have a body that also needs rest.”

The son of a luchador, he misses his friends at Arena Mexico, the 16,000-seat coliseum where he usually fights, from the parking attendants to the vendors who sling nachos and beer. He even misses the crowd’s boos and taunts and jeers.

He tries to keep the spirit alive at the crepe stand.

Each dish is named after a fighter. His favorite, which comes with cream cheese and strawberry jam, is the Olímpico, of course.

The wrestlers now getting into the street food business aren’t pioneers. That distinction belongs to José Guadalupe Fuentes Ocho, better known as Baby Face.

He grew up poor in tiny Colima state in the 1950s and started wrestling “out of hunger.”

“It was either that or wash cars,” he said.

As he neared retirement about 25 years ago, he realized he didn’t have a way to provide for his family.

So on wrestling trips to Japan, he began taking cooking lessons on his days off. When he returned to Mexico, he opened a stand, Arroces del Baby Face, outside Arena Mexico.

Wrestling took a toll on his body, resulting in surgeries to replace a knee and both hips. Now 73, with the same cherubic cheeks that earned him his moniker, he labors to get around, taking orders from his throne of pillows piled on a plastic stool.

When customers ask if he’s Baby Face, he arches an eyebrow: “I’m what’s left of him.”

Most wrestlers never achieve the fame — or the ticket sales — of Baby Face, Último Guerrero or Olímpico. Even before the pandemic, many had creative side hustles.

Gran Toro, or “Big Bull,” a hulking 36-year-old fighter who lives in Mexico state, north of the capital, worked for a small company that issues loans.

After COVID-19 tanked that business, he opened a wrestling-themed carne asada taco joint. He named it “La Huracarana” after his favorite move, in which the attacker jumps on his victim’s shoulders and wrenches him backward into a cradle.

Gran Toro — he has yet to reveal his face or his real name to fans — has not waited to get back in the ring.

Three times a week he trains with an aging fighter named Mr. Jack, who has quietly continued his workouts even though gyms remain officially closed.

A few weeks ago, to keep his students in shape, Mr. Jack hosted a clandestine match, broadcasting it at a few local bars.

Inside the cavernous gym sat an audience of 12 — mostly family members of the dozen mask-clad wrestlers.

A young man sanitized the ring with antibacterial spray as the wrestlers — a few dressed in hot pants and knee-high boots — were sprayed down with gel. The referee’s face mask matched his striped black-and-white shirt.

When Gran Toro ran out, dressed in black pants and a silver bull’s mask, there were a few weak claps. But he quickly captivated the small crowd.

For a man of 260 pounds, he was shockingly quick on his feet as he sparred with his opponent, a chiseled wrestler named Azteca Negro.

Using the ropes for momentum, Gran Toro launched himself toward his rival and flipped him out of the ring and into a row of empty folding chairs. When the wrestler cried out in pain, Gran Toro sneered: “This is lucha, not dolls!”

Moments later, Gran Toro pinned Azteca Negro and was declared the winner.

After the match, he emerged from the dressing room, wearing sneakers and jeans but still flushed.

The match had been magical, he said. “Outside of the ring, you’re just a normal person trying to eat.”

He lingered there for a bit, chatting with Mr. Jack and his fellow wrestlers. Soon he would have to head out to work at his taco stand.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.