Rams hope to reshape rowdy reputation of Coliseum in NFL circles

The stories of NFL games at the Coliseum are legendary, but not the nostalgic kind that fans remember fondly.

Fights in the stands broke out like brush fires, so frequent and so spirited in those old Los Angeles Raiders days that players would turn around on the sidelines to watch the action in the seats.

“Raider fans think of themselves not so much as spectators but as participants,” Jim Hardy, then the Coliseum’s general manager, told The Times in 1994.

That’s the reputation the Rams are looking to change as they relaunch in Los Angeles and in the stadium they will call home for the next three seasons while their $2.6-billion Inglewood stadium is being constructed.

The Rams play host to the Seattle Seahawks on Sunday in their historic home opener, the first regular-season NFL game played in L.A. since Christmas Eve of 1994, when the Raiders said goodbye to the nation’s second-largest market before moving back to Oakland. The Rams played at the Coliseum from 1946-1979, and in Anaheim from 1980-1994, before moving to St. Louis.

The world has changed since that era, as have the NFL, the Rams, and security procedures for major events such as these, with Sunday’s game expected to draw a crowd that approaches the stadium capacity of 91,000.

According to the Rams, there were a combined 10 arrests in last month’s exhibition games against Dallas and Kansas City at the Coliseum. Both games were at night, meaning spectators had more time to drink before kickoff, but those games were also meaningless in comparison to regular-season games so emotions could run higher. All the regular-season home games for the Rams have afternoon kickoffs.

At the Cowboys-Rams game, multiple fights in the stands and outside the stadium were captured on video, with some going viral on the Internet.

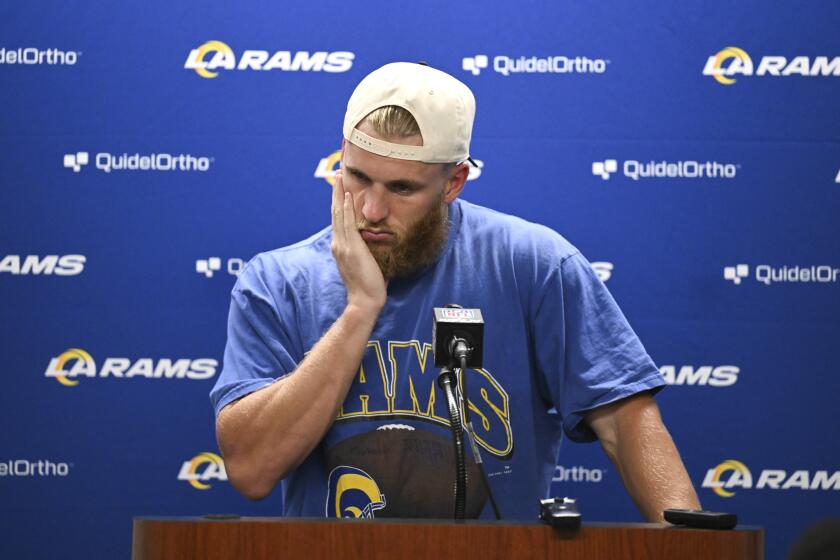

“First and foremost, we want this to be a very family-friendly atmosphere,” said Kevin Demoff, Rams chief operating officer. “There’s always going to be a few knuckleheads at any large gathering that can stain what a lot of people do. But for us, the emphasis is making sure we have excellent security at the gates, excellent security in the sections, and that we teach the alcohol sales people to make sure fans aren’t oversold.”

Alcohol is not widely sold at the Coliseum during USC games, except at four small clubs within the venue to members of the Trojan Athletic Fund. It is readily available at Rams games, as is the case around the NFL. Alcohol sales at both Rams and USC games are cut off after the third quarter.

The Rams spent $2.4 million upgrading security infrastructure at the Coliseum, installing X-ray machines at every gate, adding additional fencing and fortifying the security perimeter, and upgrading the system for fans to report incidents. The goal was to make the Coliseum as secure on Sundays as any other NFL venue.

It’s not as if the Coliseum was lawless before the Rams arrived. Security standards are different for an NFL game versus a college football game. USC games tend to have an older demographic, and the majority of the crowd is pulling for the same team. At NFL games, particularly in a huge market such as L.A., there tends to be a larger percentage of fans pulling for the visiting team.

A few years ago, for instance, when the San Francisco 49ers played host to the New York Giants in the NFC championship game at Candlestick Park, San Francisco police officers went undercover in Giants jerseys. That helped them draw out the local fans who were out to physically harass or intimidate fellow spectators. In recent years, police working other NFL games have followed suit, wearing the jerseys of visiting players.

Instead of trying to sell every seat at the Coliseum, the Rams have capped the capacity at 80,000 for the majority of games and have avoided selling the worst seats in the house. However, because of the historic nature of both the Dallas and Seattle games — first exhibition and regular-season games — the club increased the capacity to the full 91,000. Naturally, that presents additional operational challenges.

“It’s a major undertaking,” said Joe Furin, Coliseum general manager. “It’s a big operation, and to steal a line, it takes a village to make it all happen smoothly.”

Much of that village is several blocks away from the Coliseum, and on the other side of the Harbor Freeway, in a two-story building resembling a warehouse and owned by USC. That houses “Unified Command,” a beehive of activity on the day of an event that acts as a nerve center of coordination for more than a dozen agencies, among them the FBI and L.A. police, metropolitan police, sheriff’s and fire departments.

A collection of roughly 40 representatives of the various agencies are stationed in a cavernous room that looks like an air-traffic control center, with computer terminals and phone lines everywhere, tabletop Coliseum maps with resources that look like board-game pieces, video boards displaying closed-circuit camera views of the stadium and surroundings, and one TV showing the game broadcast.

“We all work in a coordinated effort to make sure that when something happens, we address it in real time,” said Angela DiBenedetto, USC’s fire safety/emergency planning specialist. She helps compile a 75-page document for every major Coliseum event that details the plan of action for every conceivable situation, from a pandemic or terrorist event; to an earthquake, water leak or fire; to how to handle injured or unruly fans.

Police officials asked that the inside of Unified Command not be photographed, and were careful not to reveal specific details about their procedures.

“There’s a lot of things here you’ll never see,” said Michel Moore, LAPD assistant chief. “The confidentiality of this place is probably only superseded by the Rams’ playbook.”

After weeks of confusion about who should pick up the tab for the extra security at Rams games, the club agreed this week to pay police costs not only for the rest of the season but for the exhibition games that have already been played. The union representing the LAPD first raised the issue, arguing officers had been removed from neighborhood patrols to work football games, and demanded the team instead pay off-duty officers overtime to work as security guards.

The Los Angeles Fire Dept. has quick-response paramedic teams on bicycles who carry defibrillators as well as other medical equipment. Meanwhile, an army of traffic officers and L.A. Department of Transportation authorities work to make sure fans can get to and from the game efficiently.

“Nobody wants to sit on southbound Figueroa and listen to the second quarter of a game with a ticket in their pocket,” Moore said.

Whereas Unified Command monitors the entire area surrounding the game, including the streets, Metro line and freeway in the vicinity of the stadium, as well as Exposition Park, Furin and his security team oversee what happens on Coliseum grounds. They have an office in the corner of the stadium, next to the peristyle, where they can see what’s happening inside the venue and respond to security issues, including those texted by spectators.

Much as the Rams are tapping into nostalgia, Demoff said, there’s no reason the Coliseum experience for fans needs to be a throwback to yesteryear.

“It’s a different fan base, a different era, and a different NFL that’s put security protocols in place, and a different franchise,” he said. “I’d be disappointed if at the end of the year people look back and say they had the same concerns as they had 22 years ago. It’s our job as a franchise to make sure the environment is positive and our fans have a safe place to enjoy the game.”

Twitter: @LATimesfarmer

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.