From the Archives: At the Northridge Meadows apartment complex, hours of terror in the rubble and dust

Editor’s note: This story originally published in the Los Angeles Times on Jan. 24, 1994.

Steve Langdon rolled over at 4:30 a.m., eyed the clock groggily and pulled himself out of bed, half an hour earlier than usual, but ready to brew some coffee.

Three doors down the hall in Apartment 101, mechanic Pil Soon Lee was already up, quietly brushing his teeth to avoid waking his wife and their two sons.

And in the northern alleyway of the Northridge Meadows apartment complex, Cary Erdman guided his car slowly toward the electronic security gate, heading to his supermarket job in Hollywood.

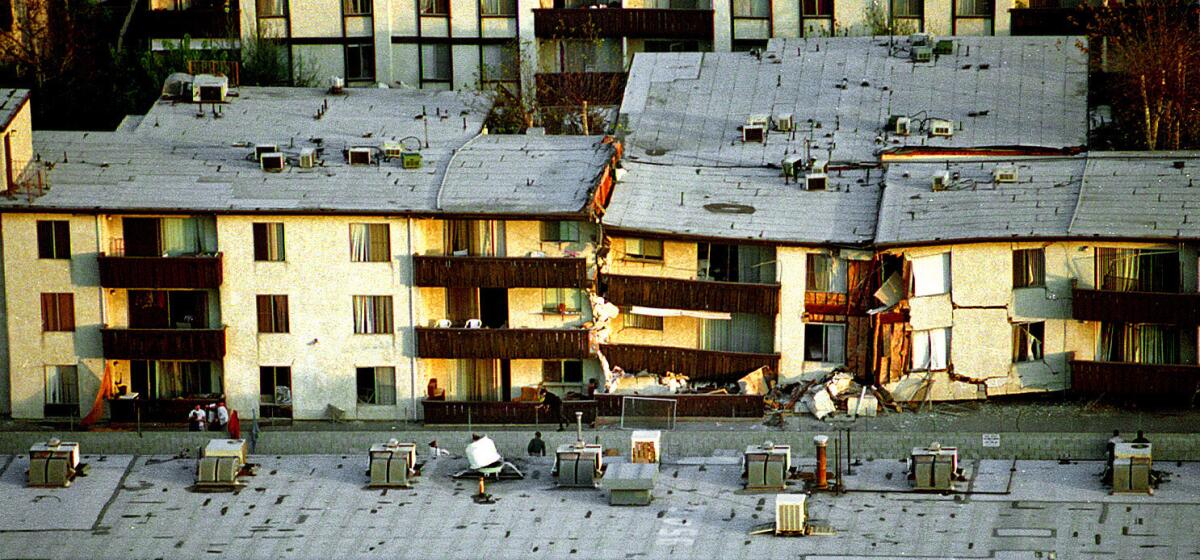

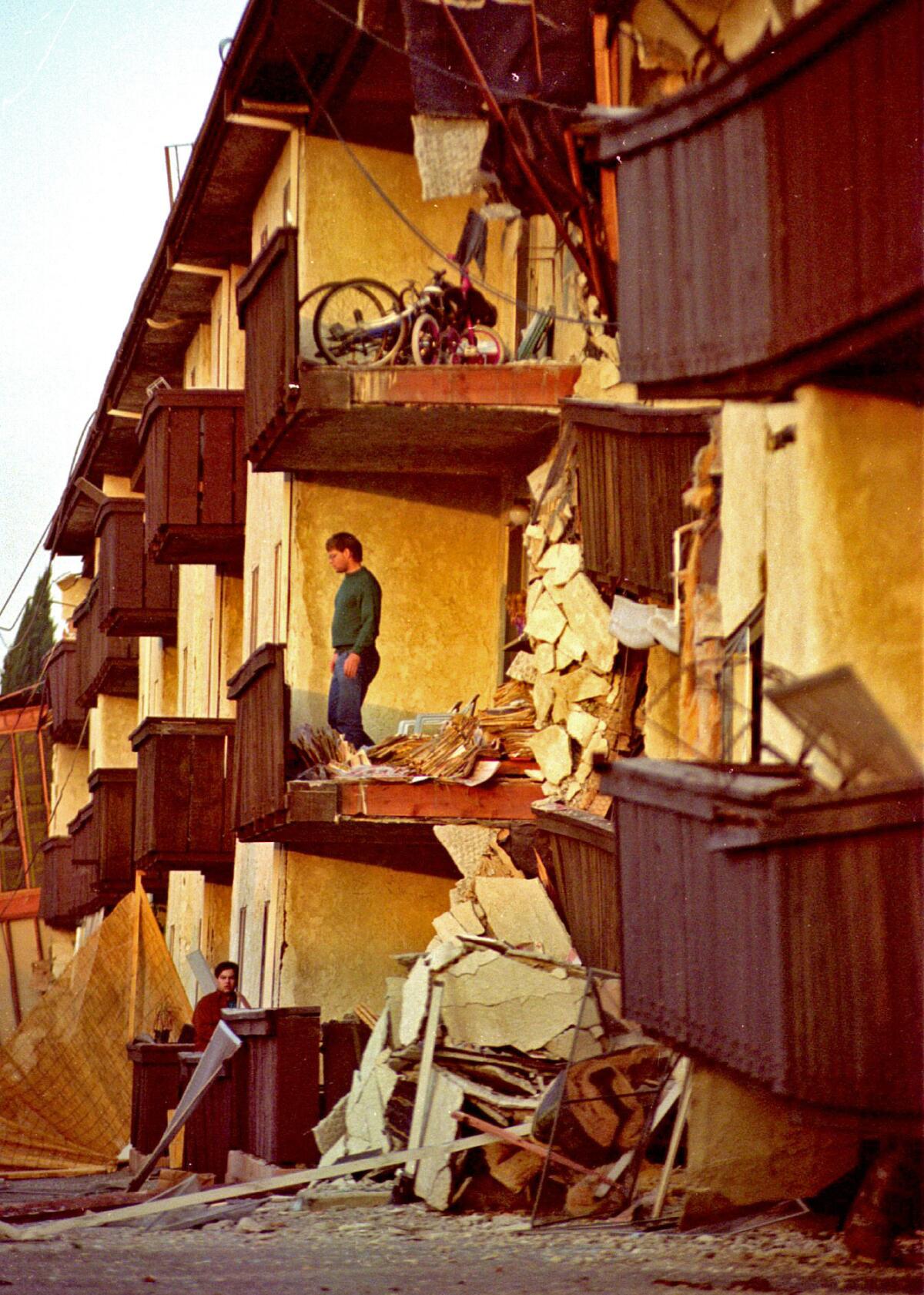

Then, as 4:31 popped up on clock radios throughout the building, daily routines came crashing down with a roar — along with the walls, stairways, floors and ceilings of a typical beige stucco San Fernando Valley apartment complex.

Erdman, 49, watched in the yellow glare of his headlights.

“I’m in the car shaking,” said Erdman, a six-year resident, “and the next minute the right side of my building is coming down.”

Fifty yards away, Scott Bui heard rather than saw as he headed across Reseda Boulevard toward his apartment.

At first “it felt like a wave — like you were standing on a surfboard,” said Bui, 20, a Cal State Northridge student who had just pulled up after driving from his girlfriend’s home in Huntington Beach.

But the shaking grew violent. The lights blew out. Dust choked the air. And Bui, knocked to his knees on the asphalt, heard a huge crash — the sound of Northridge Meadows collapsing onto its first floor.

Jolted awake in Apartment 101, Hyun Sook Lee, a nurse, thought her husband was doing something to shake the apartment. She quickly realized she was wrong. A slender woman, she literally flew through the air as the tremors intensified. When she landed, she found the ceiling on top of her. She was bruised and cut across the knee, but alive.

Some people on the first floor never knew what hit them. But others slowly died in their beds, unable to breathe as they were crushed under the weight of two stories.

Second- and third-floor residents had no idea that the complex had crunched down 15 feet and pitched north another 10.

The pulse of auto alarms, and human screams, pierced the blackness.

“Is everyone all right?” “We’re trapped!” “Oh, God, help us!”

But help from the outside would not arrive for almost an hour.

See the Los Angeles Times front pages in the days following the Northridge earthquake »

Sirens approached within the first 10 minutes, but wailed past and faded. Los Angeles City Fire Department Capt. Bob Fickett and his six-man crew saw the damage at Northridge Meadows but did not stop. Earthquake procedures demanded that they first survey the entire neighborhood.

They knew they would be back. But they did not immediately realize that a three-story complex had pancaked.

Inside, Scott Bui’s 18-year-old sister, Diana, wondered why the firefighters kept going. “I think they just drove by and thought, ‘That’s a two-story building,’” she said.

Some residents, such as Langdon and his roommate, Jerry Prezioso, 67, could do nothing but wait. In the southeast corner, in Apartment 106, both men were trapped in their bedrooms, pinned by the ceiling and walls that had splintered and fallen. They were conscious and communicating, but neither could get free.

Nails dug into Prezioso’s abdomen. Langdon’s ribs had cracked, puncturing a lung.

“I was scared, but Jerry said not to worry — that if we were alive, there had to be a reason for it,” said Langdon, 45.

The building nearly crushed Raymond Goodwin, as well as his girlfriend and two friends staying in his first-floor apartment.

“Everything started falling. All of the ceiling was falling on us,” he said.

Miraculously, it stopped just four feet short of Goodwin and his friends, who were able to scramble out.

On the north side of the complex, in Apartment 351, a prime unit overlooking the inner courtyard, Erik Pearson sprang into action. Wearing only sweats and tennis shoes, he dashed to his front door, tramping on glass and debris, and found it jammed shut. Pearson, 27, searched for another way out of the apartment he had lived in for just a month.

“We’re going to die!” his wife, Susan, shrieked.

Pearson, a certified emergency medical technician, switched into rescue mode. He went over the balcony and made his way to the ground. He ran into one of the buildings and punched his fist into a glass-encased emergency cubbyhole, pulling out a fire hose to use as a rope. He then hurried back and used the hose to help his wife escape.

Others followed his example. They flung fire hoses to residents on their balconies, shouting instructions to tie the hoses and shinny down.

Terrified by powerful aftershocks, tenants clambered over second-story balconies now at ground level, leaving behind all their possessions. Those who could spilled into alleys north and south of the complex.

Third-story dwellers groped through darkened hallways, crawling up floors that had buckled three feet high in places. They picked their way down crumbled stairwells into the courtyard.

Some of the older renters, who with college students made up the bulk of the tenants, had to be carried away from the building.

Michael Kubeisy, a freelance photographer who lived on the top floor on the western edge of the complex, relied on faith to escape an apartment riddled with gaping holes in the floor.

“I’m a Christian. The Scripture says: ‘[God] will direct your path,’” Kubeisy, 34, said. “I have no doubt that’s what happened.”

Out in the hallway, he and a friend pounded on doors, called out to those still trapped and shepherded a trembling elderly neighbor onto a hanging ladder thrown up by others.

“He didn’t want to come out. So I literally looked into his eyes and said, ‘Norm, you don’t have an option,’” Kubeisy said.

Then a familiar smell brought him up short.

“Turn off the gas barbecues! Turn off the gas!” he yelled frantically.

Survivors had lighted candles. A few in the courtyard were smoking cigarettes. Tenants aware of the danger ordered everyone to extinguish the flames. Resident Robin Dunn, a gas company employee, scrambled to shut off gas to the building.

Still trapped within the walls of the complex, down the corridor from Kubeisy, Curt Harkless hammered his way out of his apartment, although he had sprained his left hand when the floor of his bedroom fell out from under him. With the same hammer, he freed the woman next door, who pleaded for sugar and something to drink. Harkless handed her a Pepsi, one of three cans he had slipped into his jacket on the way out.

Together they inched down the hall, joined by others who kicked in doors along the way. Within minutes they descended into the courtyard, where dozens of dazed survivors were gathering.

Once a tranquil suburban sanctuary complete with putting green, swimming pool, Jacuzzi and a network of running streams, the courtyard resembled a war zone. Trees had fallen. Shattered glass was everywhere. Older residents huddled in chairs, babies bawled, and young and old hugged each other in consolation.

Mary McDonald tried to comfort her friend Elizabeth Plant, who was suffering from chest pains. Both women had managed to break out of first-floor apartments.

Jon Blatt of Apartment 263 became Northridge Meadows’ link to the outside world. With Pearson’s help, he squeezed out of the complex through a gap in the northwest wall, then ran for the fire station at Lassen Street, a mile north.

The firefighters had gone.

“There were two ladies in lawn chairs sitting on the driveway of the fire station, and I said: ‘Where are the firemen?’ ” recalled Blatt, 25. “I said: ‘Look, you have to tell them that 9565 Reseda Blvd. has collapsed. People are dying in there.’”

Firefighters, when they passed at 4:40 a.m., had noticed that the building was in trouble. But they had other problems, too: a mall collapse, several major fires and a multitude of gas leaks. It would be another 45 minutes before they could work their way back to Northridge Meadows.

Related: A big earthquake would topple countless buildings, but many cities ignore the danger »

Back in the courtyard, Beverly Reading hoped that her friend Ruth Wilhelm, 77, a recent widow who lived in Apartment 127, would appear, but she knew hope was slight.

Pearson had tried to save Wilhelm after seeing her leg protruding from a pile of beams and hearing her hoarse cries.

But when he returned with a neighbor, he was met with silence. Desperate, Pearson crawled into the tiny crevice that had been the woman’s bedroom.

“I yelled at her, shined a light in, pushed a leg, tried to get her to respond to me,” he said. “Unfortunately, she had passed away.”

Pearson wept.

Even without tears, it was impossible for anyone to see clearly. The lights were out. The moon had set hours ago. A red glow from a nearby fire brought embers but no illumination. Only a few flashlight beams sliced through the pitch darkness — and until dawn, they were the only source of light.

Worried relatives were converging on the complex.

Angeline Cerone, 80, whom everyone knew as Ann, had lived in Apartment 103 for more than two decades. When no one answered the phone, her grandson, Stephen, 28, rushed over from Van Nuys. When he peered inside what he thought was his grandmother’s unit, he was puzzled to see furniture and personal items that he did not recognize. Suddenly, he realized he was squinting into a second-story apartment, and that his grandmother’s unit was beneath.

Two doors away, Hyun Sook Lee screamed for her sons and her husband. There was no response from Pil Soon or their older son, Howard, 14, but finally 12-year-old Jason answered. His legs were pinned. Unable to move herself, she told him to fight free of the debris. He cried that he couldn’t.

“Keep trying,” his mother commanded. Finally, Jason yanked his legs free, straining so hard that he dislocated his right leg. The toes on his other foot were crushed and bleeding but Jason began crawling in the rubble.

As the dawn broke, Jason squeezed through a 14-inch-wide hole and emerged into the arms of other tenants who, hearing his cries, pulled him free. He had been trapped inside 45 minutes.

It took rescuers 15 more minutes to dig out his mother, who recited Hail Marys until she was freed.

On the other side of the collapsed entryway, in Apartment 104, a young man known to firefighters only as Robert cried out in horror. He was pinned, trapped with three of his friends. Shouting through the walls, he said he had heard them screaming. Then, helpless, he had heard them die.

For the first half-hour, fire Capt. Fickett and his crew worked alone — six men covering 160 apartments.

“We realized as soon as we got back there, ‘Holy Christ, this is major,’” Fickett said of the collapsed building.

The first round of reinforcements arrived about 6 a.m. As soon as he stepped off his truck, firefighter Jim Walter was swarmed by people telling about others trapped inside. The arrival of his company doubled the contingent of firefighters. About 20 minutes later, Battalion Chief Bob De Feo arrived from Hollywood and took charge, along with Station 73’s captain, Steve Bascom.

From their command post, a Ford Escort covered with concrete dust, the 16 firefighters made a dogged stand. They repeatedly tried to summon reinforcements on their radios, but other rescue units were busy.

They would win a few battles, then lose some.

By now it was light — 6:30 a.m., two hours after the quake had collapsed the building.

Splitting into three teams, the firefighters began a methodical search, clearing people from the second and third floors. They carried out a man with cerebral palsy, and an elderly woman who had just had hip surgery.

They broke down the door of one apartment to free an elderly man, who had started to vacuum his carpet. They persuaded him to leave, hurrying him up a corridor that tilted at a 60-degree angle.

Fickett paced the perimeter of the huge building, questioning residents who were pulling each other out of the courtyard and into the alleyway: “Do you know of anybody that’s trapped? Have you heard any voices? Have you gone around and yelled?”

Pearson and other residents struggled to finish the work they had begun, digging into sunken first-floor apartments inside the courtyard, trying to reach those still trapped. But at least five times, Pearson discovered a lifeless limb jutting from the rubble.

“Everyone keeps asking me, ‘You’re a hero, Erik, how do you feel?,’” Pearson said. “I don’t feel like a hero, because I had to see five people dead.”

Robert — firefighters never learned his full name — was freed in about an hour and taken to Northridge Hospital Medical Center. That night he was so terrified, he refused to leave the hospital. He slept in the lounge.

Prezioso had lived in Apartment 106 for 20 years, but he said two decades felt like nothing compared to the five hours he spent trapped.

He joked with his roommate that the next time they moved, “let’s get an apartment on the top floor.”

Prezioso watched as firefighters used a jack to clear away bricks.

“I can see the blue sky!” he exclaimed when freed. “It’s beautiful!”

To get to Langdon, rescuers tunneled 15 feet deeper inside the building.

They found Langdon beneath another collapsed wall, wedged underneath a chest of drawers, his head hanging off his bed and painfully pinched by rubble.

The rescues of the two men were cheered by onlookers and boosted the firefighters, who by then had seen too many bodies.

“For a while there, it was, ‘There’s another dead body. Here’s another one. Here’s another one. When’s it going to end?’” De Feo said.

Alan Hemsath, 37, trapped beneath his refrigerator in Apartment 110, was the last tenant they found alive.

His parents, Rusty and Verna, waited anxiously in an alleyway, where they knew their son would be carried out to an ambulance.

“Fifteen minutes,” they were promised over and over, but the wait seemed interminable.

“It’s the longest 15 minutes in the world,” Rusty Hemsath said.

After Hemsath was carried out, the rescue mission turned to a body recovery.

Thirteen of the 16 dead were found lying in their beds.

Many died like Sharon Englar, 58, and her husband, Phil, 62, who were found holding hands.

Jaime Reyes, 19, spent his final moments trying to shield his girlfriend, Myrna Velasquez, 18, from the collapsing walls and ceiling of Apartment 104. In the other bedroom, roommate Manuel Sandoval, who had moved in only the day before, was crushed to death.

Cecilia and David Pressman, both 72 and married for 51 years, died in an embrace in Apartment 105.

Those who slept alone covered their faces, their expressions painful proof that death was not always instantaneous.

Firefighters said these operations were particularly difficult because as they worked, crowds of friends and relatives looked over their shoulders, clinging to hope when often there was none. The aftershocks rattled nerves, and the work was arduous.

But nothing was as difficult as Fire Capt. Dave Thompson’s grim task: informing Hyun Sook Lee that her 14-year-old son, the boy who aspired to be a priest, had died in his bed.

Thompson, a veteran who flew a medical evacuation helicopter in Vietnam, approached Lee as she stood silently by the tree.

“Ma’am, listen to me. Your son, how old is your son?”

She began to cry.

“You have to talk to me. It’s very important,” Thompson gently urged. “How old is he? 14? He’s 14? Is there anyone else in the bedroom?”

She said her husband might be in there.

“Ma’am, your husband is not in the bedroom. He’s not in the bedroom. It’s just your son.”

Then, as chain saws continued whining, Thompson’s voice dropped and he delivered the bad news:

“This son is dead, ma’am. He is dead. There’s nothing we can do for him. We’ll look for your husband next.”

Pil Soon Lee’s body was the 16th, and last, to be carried from the building at 10:50 a.m. Tuesday, more than 30 hours after the earthquake.

Times staff writers Miguel Bustillo, John Johnson and Julie Tamaki contributed to this story.

From the Archives: An emerging Northridge earthquake death toll »

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.