Experts’ Heads Shake After Quakes

Were last week’s quakes in California connected? Maybe.

Did they relieve pressure on major fault lines? Perhaps, but not much.

Did they make a bigger quake more likely? Possibly.

These are not exactly the answers quake-rattled Californians are looking for.

But the recent temblors involve some of the issues that seismologists most often debate. And the more research they do, the more they sometimes disagree. Even husband and wife seismologists don’t see eye to eye.

The quakes -- including two felt across Southern California and a 7.2 temblor June 14 off the coast of Eureka that prompted a tsunami warning along the entire West Coast, followed by a 6.7 two days later -- didn’t cause much damage or injury.

They captured much attention because they came so close together and hit after a period of less-than-normal seismic activity.

One of the first questions Californians had after the series of temblors was whether there was some connection among the quakes.

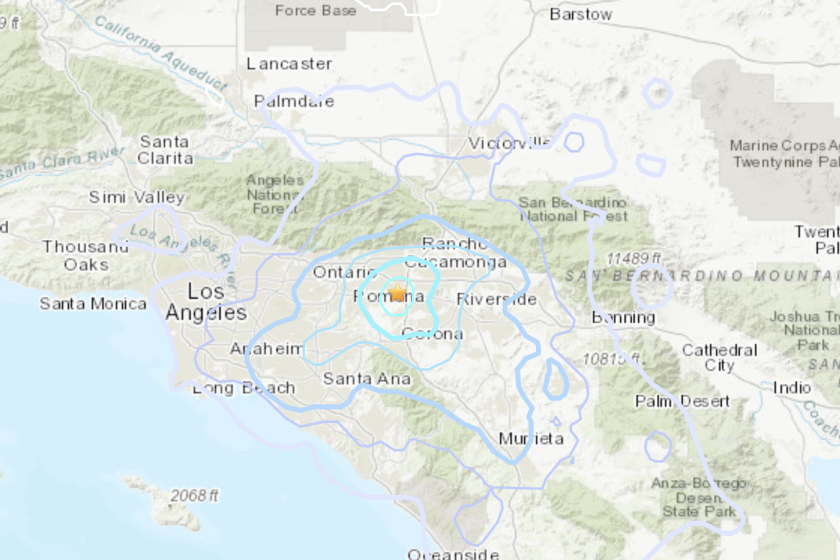

Lucy Jones, a seismologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, believes that the 5.2 Anza quake June 12 probably triggered the 4.9 Yucaipa quake four days later.

She noted that both quakes were within about 25 miles of each other and occurred on secondary faults -- the Anza quake near the San Jacinto fault and the Yucaipa around the San Andreas.

Data have shown that even a modest earthquake can trigger another quake -- even at that distance, she said.

One of her colleagues, Jones added, believes that the Yucaipa event might have been an aftershock of the Anza quake.

But Jones’ husband, Caltech seismologist Egill Hauksson, is skeptical, arguing that the temblors were too small and too far apart to have been connected

“But as you can see, some people disagree with me,” he said with a laugh.

Fellow Caltech seismologist Thomas Heaton also believes that the two quakes may well have been just a coincidence.

There is general agreement that the Southern California quakes were not connected to the ones in Northern California, mainly because of the distance between them.

Another question arising from the quake cluster is whether these temblors make a massive quake more likely.

It has long been held that earthquakes relieve pressure on fault lines, potentially decreasing the threat of a massive quake.

But experts said it was not that simple.

Heaton believes that the quakes last week were too small to significantly reduce stress on major faults.

“Little earthquakes don’t relieve pressure on big ones,” he said. “We’re always more concerned about big quakes when small ones are happening.... Big earthquakes are just small ones that never stopped growing.”

Jones said modest earthquakes do relieve some stress and may redistribute it elsewhere, but not in a significant way.

“The net change is a decrease,” she said. “But there are some locations where there is an increase.”

Jones also urged the public to keep predictions in context. Even with last week’s temblors, the chance of a bigger quake in Southern California soon afterward is still one in 1,000.

Another issue that puzzles scientists is why last week’s quakes occurred in a such a tight cluster over four days. Although the types of temblors California saw last week are not unusual, it is rare for them to occur in such rapid succession, they said.

Seismologists said one reason these quakes had gotten so much attention was because California had seen relatively few major shakers in recent years.

Big quakes have always occurred in unpredictable patterns, they said, noting that the state went through a quiet period in the late 1970s and early ‘80s, then saw several major temblors in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, including the Loma Prieta quake in the Bay Area and the Northridge quake in Southern California.

Do times of quiet seismic activity mean a major quake is coming?

“People have been arguing this for years, and this is where people really are on opposite sides,” said Paul Davis, a UCLA seismologist.

Davis said he was inclined to believe that massive quakes generally were more likely to occur after clusters of smaller quakes than after long periods of relative seismic calm.

“The trouble with these things is we need a lot of results before we feel confident,” he said.

One of the last times a major cluster occurred in California was April 1992, when the 6.1 magnitude Joshua Tree earthquake was followed two months later by the 7.3 Landers quake and the 6.2 Big Bear quake, which occurred within hours of each other.

After years of research, many scientists now believe that the three were connected. Some experts believe that the cluster lasted for years and was connected to the 7.1 Hector Mine quake in 1999.

Still, seismologists aren’t certain exactly how this triggering occurred.

Though California is a rich laboratory for seismic study, scientists are beset by obstacles.

To truly gauge how earthquakes trigger other quakes, they need to understand the state of stress deep underneath the surface of the earth.

“The huge problem is that you need to know how much rocks are stressed at depths down to 20 kilometers, and bore holes only go down five kilometers,” Davis said.

“We can present a theory that cannot be disproved until long after we are dead,” Jones added. “Unlike most scientists, we don’t get to create our experiments. We have to accept what the Earth gives us.”

Heaton said he had a stock answer for anyone who asked him when the Big One was going to strike. “I tell them, ‘You’ll know when I know.’ ”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.