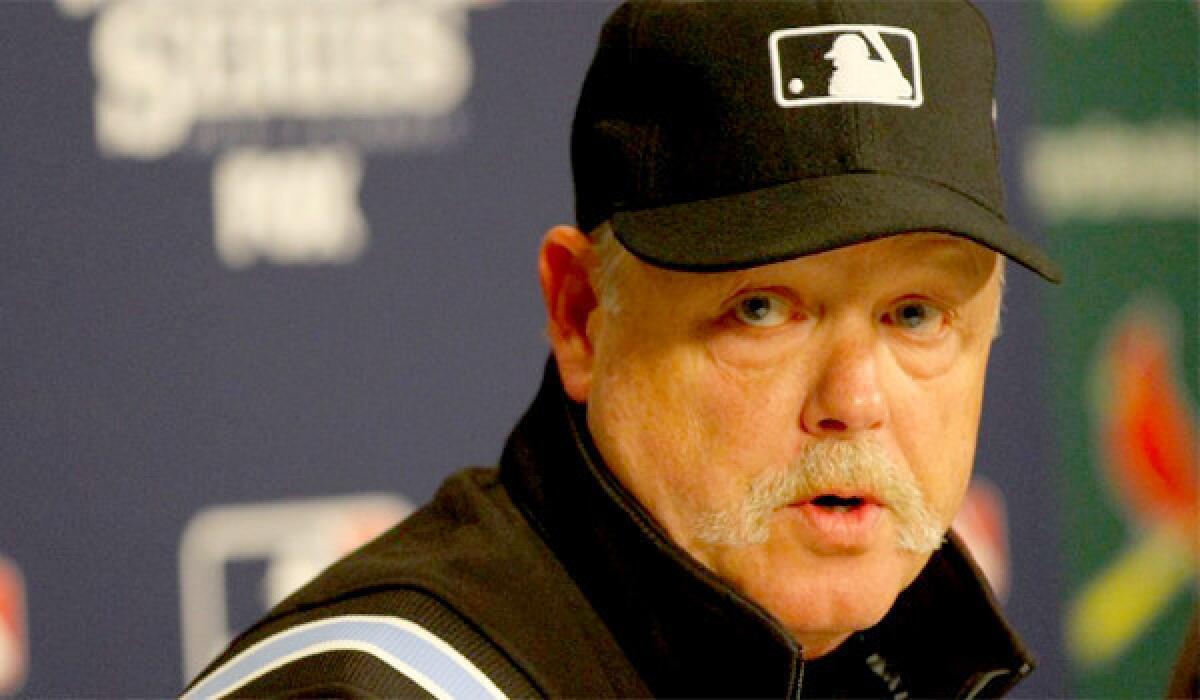

Jim Joyce has been there at some big moments

There is a leftover tidbit to this year’s World Series Game 3, when umpire Jim Joyce called obstruction at third base to end the game and send the Boston Red Sox to defeat.

When Joyce’s father died in 2009, among the things buried with him was a Red Sox cap.

“He was flipping over in his grave when I made that call,” Joyce says.

There are umpires and there is Jim Joyce. He doesn’t want to be special, other than to have people know he does a good job. But a triangle of fate and circumstance has singled him out.

Oct. 26, 2013, St. Louis, World Series Game 3

The Cardinals and Red Sox were tied in the ninth inning, 4-4, when Boston catcher Jarrod Saltalamacchia rose from tagging out Yadier Molina at the plate to see Allen Craig running toward third base. He threw to third baseman Will Middlebrooks, but the throw was wide and went down the left-field line. Craig, barely able to run because of a bad foot, scrambled to his feet and headed toward home.

But at the same time, Middlebrooks, face down near the bag, started to get up. Craig tripped over his legs and went down, then rose and headed for home, where he was thrown out by yards.

Immediately, all hell broke loose. Home plate umpire Dana DeMuth pointed to the third base umpire, who had pointed at the play the moment Middlebrooks and Craig tangled.

That third base umpire, Joyce, had signaled that Middlebrooks had obstructed Craig. Joyce and DeMuth had yelled “obstruction” several times.

“Nobody could hear us in that noise,” Joyce says, “so that’s why the immediate hand signals were important.”

Joyce’s call, and DeMuth’s implementation, meant that Craig would be ruled safe. The run scored and the Cardinals had won. For the first time, a World Series game had ended on an obstruction call.

“At the moment you are making the call,” Joyce says, “it doesn’t occur to you how big this is. Yes, it is a World Series game. But it is only a call.

“I’m not thinking there, I’m reacting. I’m only looking at what is in front of me.”

The aftermath was predictably hectic and stressful.

“I went to the plate where Dana was explaining the call to [Boston Manager] John Farrell,” Joyce says. “To his credit, Farrell never even raised his voice.”

Eventually, Joyce and his five umpiring teammates headed to their dressing room, where they were greeted by several Major League officials, including Joe Torre, executive vice president of baseball operations.

“The first thing they said, to the entire crew,” Joyce says, “was ‘nice call.’”

And so it had been. The obstruction rule doesn’t factor in intent. Soon, with the exception of hard-core Red Sox fans, Joyce’s call had been universally accepted as correct.

“The next game,” he says, “I went to work second base and nothing was said, other than the usual hellos. Nobody said a thing to me about it the rest of the Series.”

Which, of course, the Red Sox won.

Still, there seemed to be some sort of aligning of the planets that put Joyce at third base that night. We flash back.

June 2, 2010, Cleveland at Detroit

Joyce was the first base umpire. Detroit’s Armando Galarraga was one out from pitching a perfect game. He induced a routine ground ball, dashed to first base to cover, handled the play perfectly and got his foot on the bag before the runner.

Only one thing was wrong. Joyce called the runner safe. No perfect game.

Then, a funny thing happened on the way to the usual angry explosion. Sure, fans cursed, the media criticized, a couple of Tigers players slammed their gloves in disgust, but Galarraga saved the day. He shrugged, finished the game and told the media afterward that he felt bad, but knew Joyce felt worse.

Which he did.

“The kid worked his butt off all night,” Joyce said, “and I blew the call.”

The next night, with Joyce scheduled to work balls and strikes, he walked to home plate for the meeting with managers and the lineup cards. But Detroit’s Jim Leyland wasn’t there. Galarraga was, ready to hand the card to Joyce. It was an all-time gesture of sportsmanship and class. Joyce lost it.

“I cried,” he says now. “It was the defining moment of my career.”

As he left the plate, Galarraga patted Joyce on the shoulder.

“I have a picture of that hanging in my home,” Joyce says.

Shortly after the blown call, a survey asked major league players and managers to name the best umpires. Joyce finished first.

From that day in Detroit, we flash forward.

Aug. 20, 2012, Chase Field, Phoenix

In the tunnel before the Diamondbacks-Marlins game, a food service employee named Jayne Powers collapsed. There were more than a dozen people nearby, but one, Jim Joyce, on his way to his locker room, reacted the fastest.

“My degree was in health administration at Bowling Green,” Joyce says. “I knew what to do.”

Powers wasn’t breathing, had no pulse. Joyce did CPR and continued even after paramedics arrived. Her condition was so critical that the paramedics, while rolling her on a stretcher and into the ambulance, had to shock her heart six times to restart it.

Joyce’s crew tried to dissuade him from working the plate that night. He responded that the constant focus of balls and strikes would be his salvation. His wife, Kay, who had been with him, warned others against giving any updates on Powers’ condition.

But in the fifth inning, he was called to the screen behind home plate and told Powers’ condition was stable.

Jayne Powers is back at work at the stadium now. She walks three miles a day.

When she was fully recovered, she held a party and Joyce was there. Before she allowed anybody to enter, she had each person sign a pledge that they would learn CPR in the next six months. All signed.

And the calls go on

Joyce, 58, lives in the Portland suburb of Beaverton, Ore. He and Kay have son Jimmy Jr., 30, and daughter Keri, 26.

Joyce has had more than his allotment of 15 minutes of fame, and he even addressed that shortly after the Galarraga incident: “I certainly didn’t want my 15 minutes of fame to be like this. I’d rather have it come in a World Series game.”

Now, he says, “I wish I hadn’t said that. I don’t really want 15 minutes of fame. I don’t like the attention. I’m proud of my career, proud of major league umpires and what they do. That’s enough.”

Torre was approached recently in the paddock at Santa Anita, where his horse, Game On Dude, was to run in the Breeders’ Cup Classic.

There are rumors that Jim Joyce might retire, he was told. Any truth to that?

Torre got a stricken look on his face and said, “God, I hope not.”

This week, Joyce confirmed that, when it is time to play ball in 2014, he will be found near a base or behind a plate.

It will be his 27th year in the majors. America’s pastime is grateful.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.