Torii Hunter goes into retirement after building quite a legacy in baseball

Torii Hunter smiles at a news conference announcing his retirement in Minneapolis on Nov. 5.

They have said their goodbyes to Torii Hunter in Minneapolis. We need to do the same in Southern California.

Knowing Hunter, if he could have figured out a way, he would have scheduled a series of going-away news conferences. One more in Detroit and another in Anaheim. Not for his ego. For the fans and people he had met, touched and been touched back.

Those are the three major league cities he played in. Also the three places he was most beloved. He would have been beloved in any city he played. If you ever met a person who disliked Hunter, you were meeting a member of the vast minority.

Last week, Hunter sat down in front of the media and most of the Twins organization to break the obvious news, that at age 40, he was stiff and sore and that 17-plus seasons in the big leagues was going to have to suffice.

There were tears all around. There should have been sobs coming from MLB’s headquarters in New York. If there had ever been a better ambassador for the game, it is hard to come up with the name.

Had Hunter sat in front of Angels media and Angels personnel to make the same announcement, even now three years after he left, there would have been tears. Hunter probably doesn’t have Hall of Fame numbers, just a Hall of Fame presence.

The smile that lit up every room he was in, every clubhouse and every dugout, was there at his news conference at Target Field. He went out just like he carried on every day of his 2,372-game career. With a sense of humor.

“Did I say I was retired,” he said, jokingly. “No, I said I was real tired.”

He joined the Angels in 2008. He had been an All-Star twice with the Twins and would be an All-Star three times with the Angels. He was finishing a run of nine years being selected the American League’s Gold Glove Award winner in center field.

When he left the Twins, the tears of Minnesota fans were matched by those of the Minnesota media. When he arrived in Anaheim, grown men and women with microphones and notebooks in hand shed different tears, those of joy, and sank to their knees in gratitude while looking heavenward.

To say he was a clubhouse presence is to say it is often sunny in Southern California. He took over. Not because he needed to or wanted to. He just did. It was his way, something he said he learned from being around the late and great Kirby Puckett when he was a young player and Puckett was the clubhouse veteran.

Hunter was the antithesis of the spoiled, all-about-me pro athlete.

When young outfielders came up to the big team, more often than not, Hunter took them out and bought them a suit.

When it was the first payday for the newbies, those who had ridden the buses of the minor leagues and lived on team per diems that were maxed out at McDonald’s, Hunter assumed the role of mailman.

He would gather as many teammates as he could find to watch as he handed the first major league paycheck to the youngster. Even an MLB minimum check would knock the youngster on his back. The look on the young player’s face was priceless, and Hunter’s joy at that look was the same.

One who opened his first MLB paycheck amidst Hunter’s group-gathering was Peter Bourjos, the young outfielder who could run like a deer. In 2010, partly because of Bourjos’ presence, the Angels moved the league’s best center fielder to right field.

Controversy? Not a hint.

“I’ve got a 100,000-mile warranty on my legs,” Hunter told ESPN’s Tim Kurkjian, “and the warranty is up.”

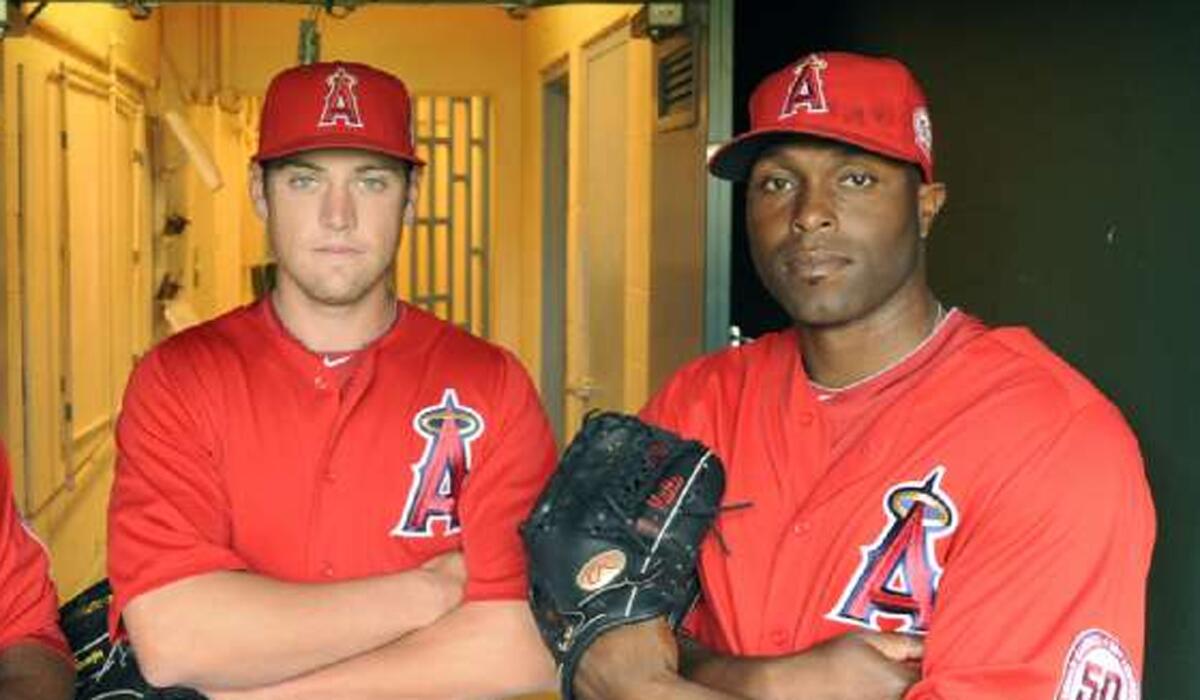

Bourjos was a wide-eyed, 23-year-old then, who, as anxious as he was to play the position he loved the most, was slightly traumatized by being the one to force a legend to move. Hunter took care of the trauma immediately.

“He came to me,” Bourjos said, “and told me to let him know what he could do to help.”

Torii Hunter, right, often took young outfielders under his wing, including Peter Bourjos , right, during his time playing with the Angels.

Another young outfielder who spent part of two seasons with the Angels was Chris Pettit. Hunter took Pettit out and bought him a suit. Always looking for the best laugh and most fun, Hunter tried a different twist on Pettit with the paycheck routine.

“He handed me his pay envelope,” Pettit said, “and asked me to open it up and read it to him. He said something silly about not being able to see the numbers. I opened it up, looked at it and left out one digit. I said something like, ‘It says $70,000.’

“He panicked for a minute, but then he laughed. He loved a good joke. He was just a great guy.”

Hunter was drafted by the Twins, came up in 1997 and stayed through 11 seasons. He was with the Angels from 2008 to 2012, had two seasons in Detroit and, fittingly, went back home to Minneapolis for 2015 and his last hurrah.

The Twins were, unexpectedly, in the playoff race until the last week of the season. In his final season, Hunter played in 139 games, hit 22 home runs, drove in 81 runs and batted .240. No going out with a whimper for the pride of Pine Bluff, Ark.

In his 2,372 major league games, he had 2,452 hits, 1,391 RBIs, 353 home runs, a batting average of .277 and an on-base percentage of .331. He once had a 23-game hitting streak. He also once hit three grand slams in one season.

But in this case, statistics don’t make the man. Not even close.

To Torii Hunter, the ultimate, consummate, unmatchable big league person, Southern California says goodbye and good luck.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.