Emergency Network Will Lose Another City; 4 Will Be Left

Everyone involved agreed that the idea was sound: a centralized, state-of-the art computerized police and fire dispatch service for nine South Bay cities and Culver City. By pooling resources, the cities would have access to the latest in communications technology at a fraction of the cost, while relieving crowded emergency radio frequencies.

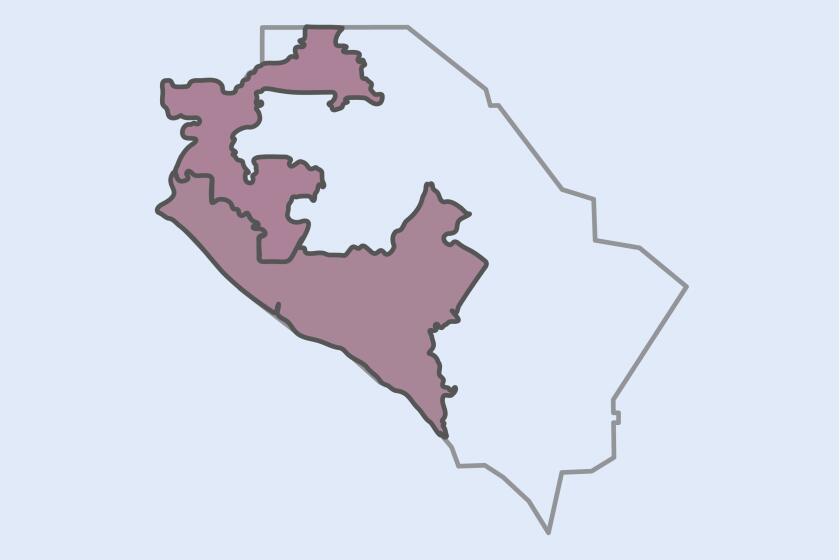

But as with many efforts at regional cooperation, what makes sense in theory has proven difficult in practice. What was planned in the early 1970s as a 10-city South Bay Regional Public Communications Authority apparently will dwindle to four cities next year.

The Hermosa Beach City Council has announced that it will drop out of the agency--commonly referred to as the RCC, for regional communications center--effective July 1, 1988. Although the city’s police union supports the system, city officials believe the city can do its own dispatching just as well and at lower cost.

‘Bottom Line’

“I have no problem with the RCC,” said Steve Wisniewski, the city’s director of public safety, who recommended pulling out of the agency. “The bottom line is dollars and cents.”

But more than money has been involved in the shrinking participation in the regional system headquartered in Hawthorne.

Over the years, the issues of response time of emergency vehicles, local control and even psychology--whether residents would understand why their call to police was answered in another city--all have come into play.

“Joint power authorities . . . are just fraught with inherent difficulties,” said Redondo Beach City Manager Tim Casey, whose city pulled out of the system in 1983. “It’s natural for cities to pride themselves on their individuality . . . so it is difficult to compromise on things even if such compromises contribute to the greater public good.”

“It is extremely hard to get cities together on most things,” said El Segundo City Councilman Carl Jacobson, who represents his city on the agency’s board of directors.

Seven-Year Pact

Despite the latest defection, the agency, with its remaining four cities--El Segundo, Gardena, Hawthorne and Manhattan Beach--is almost certain to continue well into the next decade. Officials of those cities have met twice in the wake of Hermosa Beach’s announcement May 26, and in the next few weeks they are expected to make a seven-year commitment to the agency and to authorize the purchase of new equipment.

“We could do it cheaper,” Hawthorne City Manager R. Kenneth Jue said, “but not at the same level of service.”

Gardena City Manager Kenneth Landau said that even though the four cities will have to pick up some of Hermosa Beach’s cost in fiscal 1988-89, the agency will still be the most cost-effective approach to emergency dispatching for his city, which is larger and has greater demand for emergency services. “It’s not even close,” he said of the cost.

Robert J. Benson, the agency’s executive director, said Hermosa Beach is making the wrong decision by pulling out, but that the move won’t damage the system.

“In some ways this is a step forward,” he said. “Since 1982, we have operated on a year-to-year basis. Without long-range planning, you can’t be as effective.”

Having four cities committed for seven years will give the agency more stability than it’s ever had, he said.

There were some area officials who questioned whether the RCC, which dispatches police, fire and paramedic vehicles, would ever survive a troubled beginning.

Almost immediately after police chiefs from the 10 cities began talking in 1971 about pooling dispatch services, Culver City officials pulled out, saying their city was too far north to participate in the program. Torrance officials withdrew the same year, saying they were happy with their own dispatching service.

In 1975, Inglewood abandoned the program after a majority of the city managers involved voted to locate the center in Redondo Beach rather than in Inglewood.

When the $5-million center, funded primarily by federal and state grants, finally went on line in August, 1977, it was beset with problems.

The system is designed to feed information from callers into a computer that pinpoints the location of the incident and finds the nearest available emergency vehicle. Dispatchers then relay the information electronically to digital terminals in the vehicles.

Participants admit that the system did not always work as it should in the early years because of equipment failure, personnel problems, under financing and poor management.

There was a high turnover of dispatchers and low morale. Ineffective management was attributed to a 42-person, six-committee ruling structure that included elected officials, city managers, police and fire chiefs, police officers and firefighters.

Dispatchers were poorly trained and underpaid, earning as little as $15,000 a year in 1981. Police were improperly trained on new equipment and police officers sometimes become so frustrated that they would simply turn off their mobile monitors, forcing dispatchers to use the radio, officials said.

Slow Responses

There were many complaints about slow responses to crimes and fires. And there was the psychological factor of residents dialing the police emergency number and having the phone answered at the center two communities away.

“People are more sophisticated now,” Manhattan Beach City Manager David Thompson said. “They realize that the location of the dispatch center has nothing to do with response time. People can still call their local police station for non-emergency calls.”

The agency had four directors in its first four years. The second director, Tom Moyer, left in the summer of 1980 after it was learned that he had secretly held a similar position in San Bernardino for several weeks while heading the RCC.

Benson, the current director, arrived in February, 1981. He is credited by the participating cities with turning the agency around.

Moved to Hawthorne

Salaries were improved, with dispatchers now earning up to $25,000, and the center, which had been headquartered in a converted underground pistol range in the Redondo Beach Civic Center, was moved to Hawthorne.

Worn equipment was replaced, better maintenance provided and the workplace was spruced up, including the addition of a lunch area with an outdoor patio.

Agency officials say they now dispatch fire trucks in from 12 to 18 seconds after a call comes in, and that police cars are sent on high-priority calls in about 30 seconds.

But the improvements did not come without a high price tag.

Poor Reception

In 1982, a year after Palos Verdes Estates pulled out--citing trouble receiving transmissions because of the Peninsula’s hilly terrain--the remaining six cities received a proposed $2.8-million budget, a 51% increase from the previous year.

That budget was eventually reduced by 10%, and approved by the cities, but the following year Redondo Beach left the system.

Casey, the Redondo Beach city manager, said his city pulled out because the other cities could not afford to pump in more money to pay for the dispatching equipment he wanted. By providing its own dispatching, the city is paying about $200,000 a year more than it would have if it remained in the system, he said.

“We were feeling frustrated that we could not get the more technically advanced equipment,” Casey said. “We wanted to move ahead and didn’t see the RCC moving quick enough.”

Voice System Adopted

Another factor was the reluctance of Redondo Beach police officers to accept the silent video dispatches in which a message comes up on a small television-like screen. After officers complained that the dispatches prevented them from knowing what other patrol cars were doing, the city adopted a voice dispatch system.

Hermosa Beach officials say their decision to pull out is based purely on economics. Wisniewski, who heads both the police and fire departments, conducted a study and concluded that the city could save up to $673,577 over a seven-year period by becoming independent.

Hermosa Beach, which paid the agency $82,000 in 1979, will contribute $241,963 in the fiscal year beginning July 1. Under a system based on the amount of use a city makes of the system, Hawthorne will pay the most, $708,231.

Wisniewski, who intends to hire five dispatchers so that someone will be on duty 24 hours a day, said the cost of high-tech equipment has come down enough to allow a city the size of Hermosa Beach to have a state-of-the-art system.

Savings Diminish

“Back when the RCC went into existence, equipment was very expensive,” he said. “It was cost-effective. But now we have reached the point that the cost savings are not what they used to be.”

Hermosa Beach City Councilman Jim Rosenberger agreed: “We are the smallest member of the RCC. If you look at our analysis, it was the prudent thing to do.”

Palos Verdes Estates Police Chief Monte Newman also argues that a small city may not need mobile digital terminals and other such advanced equipment--although Hermosa Beach does plan to buy such terminals.

“At our level, we don’t really need it,” he said. “Our workload is not that high.”

Among the critics of Hermosa Beach’s pull-out is the police officers’ union. Detective Wally Moore, president of the Hermosa Beach Police Officers Assn., said officers were not consulted on the decision.

He would not explain all the reasons that the officers don’t like the move, but said the union intends to send the City Council a letter outlining their concerns.

‘Is Cheaper Better?’

“We know we can do it cheaper, but is cheaper better?” Moore asked. He said that if a police chase begins in Hermosa Beach and extends into other cities, dispatchers will have to notify neighboring agencies one by one by telephone. The regional center can notify police in several cities at once via the video terminals, he said.

“Communication is the most critical thing in police work. We have to get rid of this isolationist attitude,” Moore said. “We have to share information with these other police agencies. If we need assistance, we don’t need it in five minutes or two minutes. We need it now.”

But regional cooperation in emergency communications is not likely to get better, most city officials say.

The bottom line is control, according to Torrance Mayor Katy Geissert.

“It’s a question of whether we relinquish control to a regional body or if we think we can do a better job ourselves,” she said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.