Quakes Not Only Fear at Shabby Units : Tenants Leave Tents, Return to Building

The good news is that more than 150 people are moving out of the parking lot where they have been camped since the Oct. 1 earthquake. The bad news is that they are moving back home.

Home is a four-story, 60-year-old brick and masonry building on the edge of the Garment District where many of them work. Above all, it is gloomy, its dark hallways lined with old, torn linoleum floors, its small apartments crawling with cockroaches, mice and fleas that bite children in the night no matter how much Raid one sprays.

“Not even in Mexico did we live outside like this,” said Flora Bruno, who was camped out with four children under a tarp in the parking lot of the L.A. Mart across the street for two weeks. “But when we go inside, it is to the same place we left. They always promise to make it better, and sometimes they make repairs. But they don’t really fix anything. It is always the same.”

Declared Safe

A week after the earthquake, city seismic inspectors declared the building safe to re-enter. Yet, during most of the past decade, city health, fire and safety inspectors have issued citations to the owners for literally hundreds of code violation.

Hence, the building is considered officially safe to live in--but in violation of city habitability codes.

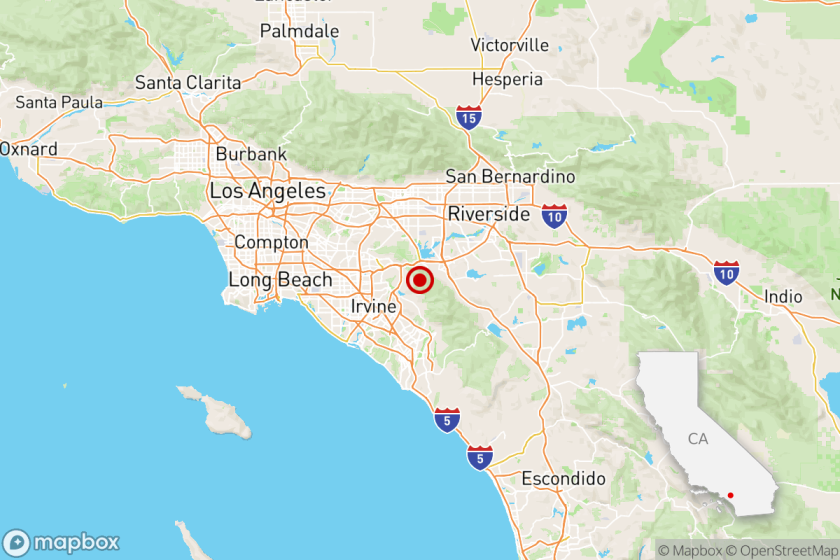

Throughout Central Los Angeles, thousands of residents, many of them newly arrived immigrants with memories of devastating earthquakes in Mexico and Central America, have been returning to buildings that are far different than the dream homes they imagined when they left for the United States.

Few buildings, however, are as notorious as this one. For nearly a decade, the block-square complex has been the target of almost constant surveillance by officials and Legal Aid attorneys seeking to help the tenants of the building, which has entrances at 1821 and 1839 S. Main St.

In 1979, then-City Atty. Burt Pines led TV crews through the hot, dingy corridors to “send a message that we mean business” to slumlords. The owner, Beverly Hills neurosurgeon Milton Avol, was fined $3,000 for fire code violations.

Since then, Avol has been the defendant in two civil suits filed against him by tenants and a variety of criminal complaints and probation violations filed by the city attorney’s office. In 1983, Avol settled his first civil suit and made repairs on the building.

“I watched heaters go into rooms that had never had heat and screens go on windows that had never had screens, and I thought, ‘Well, here is one success,’ ” said Gary Blasi, a Legal Aid Foundation attorney who represented the tenants.

Repairs Short-Lived

The repairs were short-lived. In 1985, attorneys started all over again, filing yet another civil suit against Avol with familiar complaints on behalf of new tenants. That same year, he was sentenced to 30 days in jail for problems at another building and another 30 days of house arrest in one of his own buildings.

Shortly after he was sentenced to yet another nine months in jail for probation violations last year, he sold the Main Street complex for a reported $2.25 million. At the request of tenants’ attorneys, it was placed in receivership and some of the profit went into an account for future repairs.

Michael Bodaken, a Legal Aid attorney in the case, said about $50,000 has been spent for badly needed hot water heaters. But nearly $200,000 more earmarked for repairs just sits in the account.

A principal reason for the delay is that Avol is contesting the need for repairs he claims he already made. The new owners, Hyoung and Sook Pak of Rolling Hills, contend that Avol did a slipshod job on the repairs he did make and did not make other repairs at all. Each dispute must be settled in court.

On Tuesday, Pak pleaded no contest to nine counts of various code violations and was sentenced to pay $8,500 in fines, $3,700 restitution to city agencies and $5,000 to a neighborhood center that works with the tenants.

In the meantime, the earthquake struck and most of Pak’s tenants moved outdoors. Stringing blankets and tarps between cars and a chain-link fence, they said they preferred to camp outdoors despite proclamations by city inspectors that the building was safe.

Owners of wholesale furnishing and gift stores inside the L.A. Mart raised about $800 for food and clothing to give the dislocated tenants camped in their parking lot. The owner of the gas station on a nearby corner opened his restroom to them. Everyday the tenants organized work crews to sweep the site clean.

They pointed to plaster hanging loose from the ceilings of corridors and a rubble of bricks that fell from a parapet and questioned the safety of the building.

“I was going upstairs and a brick fell right down in front of me,” Bruno said. “They say the building is safe. But it didn’t seem safe to me.”

Finally, by Wednesday, most of the tenants agreed to move back in after the Paks tore out the hanging plaster and promised tenant attorneys they would hire security guards to protect the building from gang members who frequent it at night.

Tenants’ attorneys have encouraged them to return, pointing out that they are on the verge of court hearings they expect will result in repairs to the building once and for all.

Unless the earthquake complicates matters.

“The fact is that the earthquake only loosened plaster in most of this building because it needed to be repaired in the first place,” said Barry Litt, one of the tenants’ attorneys. “But God’s a convenient person to blame, and you’re going to have a hard time suing him for damages.”

Though no one has yet proposed it, attorneys say there is a slim possibility that the needed repairs are so costly that the building may be torn down instead of being repaired, ending nearly a decade of lawsuits.

Tenants’ attorneys say they will oppose demolition of the building because low-income housing is so scarce in Los Angeles. But, should it be demolished or converted to another use, city law requires landlords to pay families up to $5,000 in relocation benefits.

Some tenants said they will stay simply because they cannot afford the deposit and first and last months’ rent for a new apartment. Rents at this building run about $270 for a one-room apartment with a tiny kitchen and bath. For tenants who make $100 a week sewing at garment factories nearby, other housing is virtually out of the question.

But others say they are thinking of leaving no matter what.

“Before we left Mexico,” Angelica Gandarilla said, “I dreamed that we would be living in a nice home here. Instead, we’re living like pigs.”

Not exactly. Her two children, though covered with flea bites, were clean and neatly dressed with bows in their hair. Her apartment, though cracked and filled with tiny cockroaches, was tidy.

“My husband and I thought our life would be better here,” she said. “But I think this earthquake may be the last straw. We haven’t decided yet. But I think we may go home.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.