Girding for the Big One : Disaster: Doomsday scenario predicts devastating effects in San Diego if an earthquake registering 6.8 on the Richter scale should hit.

It could be any gorgeous day in San Diego County, where 2.4 millionpeople go about their business with the false notion that devastating earthquakes strike only other parts of California.

From the top of Mt. Soledad, the city looks resplendent, the buildings and bustle of human activity set amid the sheer beauty of natural topography. Immediately to the west, the colored dots of cars glide undisturbed along Interstate 5. To the south, man-made Mission Bay beckons tourists and residents alike. Three miles farther down the coast, a booming downtown is securely nestled against crescent-shaped San Diego Bay.

One reason for the awe-inspiring scenery is something that lies deep within the crust of the earth:

The Rose Canyon Fault.

Eons ago, the geological fissure groaned and gave birth to 822-foot Mt. Soledad, the enviable hills of La Jolla, the sweeping drop to the ocean, the bay. Yet it has been relatively quiet for 100 years, prompting most seismologists to regard it with little more than benign neglect.

All that will change radically in a few seconds. On this otherwise unremarkable day, the fault gives San Diego a swift kick.

For 15 seconds, a southern strand of the fault reverberates with a force registering 6.8 on the Richter scale. With that wrenching power, the city and its thriving environs are thrown into devastating chaos.

So predicts a doomsday scenario being prepared by state Department of Conservation geologists, who were asked by local disaster officials to help plan emergency response to a major earthquake. An undated draft copy of the 167-page scenario, obtained by The Times, uses historical data and scientific theory to describe a shaken and battered post-quake San Diego.

The imaginary quake is smaller than the 7.1 jolt that rumbled through Northern California in October, 1989, killing 63 and causing more than $7 billion worth of damage. Even at its worst--an estimated 6.8 on the Richter scale--the Rose Canyon Fault is not thought to be able to cause nearly as large a quake, nor act up as often, as the San Andreas and related faults in Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Yet, at its worst, the hypothetical event is strong enough to deliver a succession of blows worthy of a well-trained terrorist, group--snapping transportation corridors, crippling utilities, knocking over structures and playing havoc with tens of thousands of residents.

Landslides would destroy La Jolla homes and cave in on Mission Valley hotel guests. Historic structures in the Gaslamp Quarter would topple and newer high-rises tilt. Weakened to the point of failure, area dams would threaten to unleash tidal waves upon San Diego Jack Murphy Stadium, Interstate 8 and Sea World.

Lindbergh Field would be inoperable and the San Ysidro border crossing shut down. The ground around Mission Bay and San Diego Bay would seem to melt. Hundreds of motorists would flee an impassable I-5, where the pavement would be twisted and cracked like days-old licorice. The earthquake’s force would break windows, jam doors and rain ceiling tile on horrified students and teachers in area schools.

Emergency crews would be forced to negotiate a maze of cracked surface streets, a harrowing task complicated by the raw sewage, water and natural gas bleeding from broken mains.

“It should be assumed that there will be numerous persons with injuries requiring medical treatment,” the draft report says. “Sufficient medical facilities should be functioning to care for the injured, but damage to the road network will hinder movement of the injured to those facilities.”

The draft report is the fifth such scenario written by the conservation department’s Division of Mines and Geology. The others focused on major earthquakes in San Francisco and the Los Angeles area. The lead author of the San Diego report is Michael S. Reichle, a former UC San Diego researcher who is now supervising geologist in Sacramento in charge of the state’s geohazards assessment program.

Joseph I. Ziony, assistant director for the Division of Mines and Geology, said the final draft of the San Diego scenario will be discussed at a press conference next month. He declined to discuss the final draft, which has not even been seen by local disaster planning officials and urged The Times not to run a story about the report before state officials are prepared to interpret its conclusions for the public.

“My main concern is that the report doesn’t unduly alarm the public, and that the people responsible for emergency response get a copy of it first,” Ziony said.

The draft report obtained by The Times was circulated to seismic experts for peer review. It is missing several maps that delineate the areas of San Diego that would suffer the greatest damage, as well as the locations of schools, hospitals and public buildings closest to the epicenter of the hypothetical quake.

A local disaster official, however, said the descriptions offered in the draft report can be considered gospel for emergency planning.

“It was written by people who are familiar with the type of soil that we have here and the type of surface movement that we expect,” said Jim Phelps, operations officer with San Diego County’s Office of Disaster Preparedness. “It looks as if it is going to be pretty close to what is going to happen in an earthquake of that type.”

When and where will it happen? Nobody knows.

“There are many faults in the area that may be capable of generating damaging earthquakes, and it is not presently scientifically possible to identify which of those will be the source of the next seismic event,” the draft scenario says.

But the once-ignored Rose Canyon Fault is a leading candidate, said Thomas Rockwell, a San Diego State University geology professor whose recent work demonstrated that the rift is not to be underestimated.

The prehistoric force that created San Diego’s beauty is likely to revisit the city with destruction, he said.

“That’s the literary irony,” Rockwell said. “The Rose Canyon Fault made San Diego what it is.”

The earliest record of a damaging earthquake in San Diego was in November, 1800, when a tremor of an estimated magnitude of 6.5 shook the San Juan Capistrano and San Diego missions. Other temblors have rocked San Diego since then, but the region has been “lulled into a false sense of security” in recent times, Phelps said.

“From 1935 to 1985, we didn’t have an earthquake in this county that was over 4.0 magnitude,” Phelps said. “For those of us who lived here all our lives, we didn’t think much of them.”

Then came July, 1986. A 5.3-magnitude earthquake struck 25 miles west of Solana Beach, along the floor of the ocean. It caused $500,000 worth of damage in Oceanside and led to the death of an elderly San Diego man, who was buried under an avalanche of books in his residential hotel room. Meanwhile, SDSU’s Rockwell was shaking up what seismologists had concluded about San Diego in another way. He and two Los Angeles consultants last year reported a startling discovery after excavating portions of the Rose Canyon Fault lying under a San Diego Gas & Electric parking lot near I-5 and Damon Avenue.

The fault in question is actually a series of strands, more or less connected end to end. Starting in the ocean floor west of Oceanside, they generally run down the coast, except for their detour underneath the heart of San Diego.

The strands enter La Jolla Cove, hug the eastern base of Mt. Soledad, then cross between Old Town and Mission Bay. From there, they splay into three separate fingers, which continue through downtown, cut underneath San Diego Bay, bisect Coronado and head back into the ocean toward Mexico.

Seismologists have long thought the fault to be inactive. But Rockwell and his colleagues found evidence that it has disturbed the surface as recently as 1,500 years ago.

Based on that work, state geologists are upgrading the fault to “active,” and another study by Rockwell theorizes that portions of the Rose Canyon Fault could unleash a major earthquake between the magnitude of 6 and 7 as often as every 300 years.

“It could be anytime in the next few hundred years, because we don’t know when the last earthquake happened precisely,” Rockwell said last week. “If the last earthquake was 500 to 1,000 years ago, then another earthquake might be right around the corner.”

The biggest temblor is expected to cause one side of the fault to “slip” about 3 feet. That contrasts with movement of 6 to 7 feet during the San Francisco Bay Area quake last year.

The bleak scene is described in bureaucratic prose in the state scenario. Intended to address the possible physical damage a temblor would cause, the report does not address the potential casualties and fatalities. It also does not specify the time of day or year of the quake, something experts say plays a heavy role in determining the extent of injuries and deaths. A rampaging flood through a shopping center, for instance, would be more dangerous on Saturday afternoon than before dawn on a Tuesday. A quake during a wet season would favor rockslides, while one in a dry season would ignite more fires.

The following description of a quake-torn San Diego presents the worst that could possibly happen when a 6.8 quake hits a part of the Rose Canyon Fault known as the Silver Strand. It is taken primarily from the draft state report, with supplemental material gleaned from interviews and the latest version of San Diego County’s emergency plan.

The state report does not predict a quake, but it does predict the physical damage that might occur should San Diego be hit with a major temblor.

In less time than it takes to watch a television commercial, a southern branch of the Rose Canyon Fault rumbles and slides 2 feet. The shifting earth extends 24 miles from the San Diego Police Department headquarters, 14th Avenue and Broadway, to the ocean floor off the Mexican coast.

Since very little of the Silver Strand of the Rose Canyon Fault is onshore, the damage caused by the ground movement itself is minimal. Fewer urban “lifelines” of fuel, gas, water and sewer pipes are instantly severed than if the quake had disrupted the surface farther north on the fault, say through Old Town or in La Jolla.

But that is just a momentary consideration. The fault’s 15-second shrug emits pulverizing shock waves through the soil that deliver a ferocious one-two punch to surrounding areas.

First, the surface shakes, then there are dozens of aftershocks.

The quake triggers landslides down Mt. Soledad, ruining expensive hillside homes and smothering Ardath Road, La Jolla’s main link to the rest of the city. Rocks fall, too, along the commercialized southern wall of Mission Valley; the canyon walls of Otay Mesa; the cliffs of Point Loma, and in the suburban reaches of Murphy Canyon.

Along San Diego Bay, through the Tijuana River Valley and southeast of downtown, the ground shakes with enough power to knock unbolted wood-frame homes from their foundations and to topple old, unreinforced masonry structures.

Other areas are more fortunate: They shake with a bit less intensity, but still enough to take down many unreinforced brick chimneys and knock over a few walls. They include Sorrento Valley, Pacific Beach, La Jolla Shores, Mission Hills, Hillcrest, East San Diego, El Cajon, Santee, the mesas east of National City and Chula Vista, the high parts of Otay Mesa and much of Tijuana.

After the surface shaking comes evidence of the second--and most destructive--punch from the earthquake. The shock waves will precipitate the “liquefaction” of compacted fill, old flood plains and low-lying coastal areas with high water tables.

In layman’s terms, it will rearrange the silty soil and turn it into the geologic equivalent of pudding. Streets, pipes, even “earthquake-proof” buildings, will sag, snap and shift. In places, whole clumps of earth will split or drop.

Most vulnerable are San Diego’s monuments to tourism and commerce--Mission Bay, Shelter Island, Harbor Island, the lip of San Diego Bay, Lindbergh Field, Mission Valley. Other targets are the fringes of North County lagoons, the Tijuana River Valley and areas as far east as the El Cajon-Santee basin.

Liquefaction is instantaneous during the earthquake, but the earth won’t start sagging or cracking until after the first tremor and could continue shifting for hours, especially within 20 miles of the Silver Strand Fault.

Combined, the shaking and liquefaction acts as a particularly menacing force, aided unwittingly by the city’s historic growth patterns and its past ignorance of the Rose Canyon Fault’s potential for mayhem.

Buildings

In the heart of downtown, the historic Gaslamp Quarter is among the most hazardous places in the city.

The reason: The quaint quarter holds the greatest concentration of older buildings considered the most likely to cave in during an earthquake, say city planners. Other imperiled structures dot the mid-city street along El Cajon Boulevard and University Avenue.

In all, there are 760 of these unreinforced masonry buildings, constructed before earthquake standards imposed in 1933. Those buildings that have not since been retrofitted collapse when load-bearing walls buckle and give way during the temblor.

City planners say their current list of older buildings includes the landmark Spreckels Theatre, built in 1912. The landmark has not been retrofitted to protect it against an earthquake, but building manager Colin Stillwagen said private engineers have predicted that it would withstand a temblor of 8.5 magnitude.

A few blocks away, the city’s newest high-rises sustain heavy damage, too. The problem is not internal, but the liquefied ground that causes them to sway, bounce and--in the worst cases--shift. The same is happening in Coronado, Mission Valley and along Mission Bay, where the strength of each building’s foundation is tested as never before.

In public schools, the quake horrifies teachers and students--overturning bookcases, breaking windows, flinging down ceiling tile and jamming doors in at least 10% of the classrooms within 10 miles of the Silver Strand Fault.

Almost all of the schools south of Pacific Beach and Mission Valley are in areas that sustain the heaviest shaking. Those include structures such as San Diego High School, which is within 1 mile of the fault, as well as two schools in the South Bay and three others between Coronado and Pacific Beach.

Those least damaged will be the elementary schools, usually one-story, wood-frame buildings. Two-story secondary schools will have to be inspected by professional engineers to determine whether the structures are safe.

In either case, teachers must calm their hysterical pupils because the mangled network of roads prevent parents from getting through.

Compounding the chaos is the growing parade of dazed homeless and injured people crowding into some school gymnasiums, converted by emergency officials into mass-care centers.

The quay wall along the B Street Pier fails, as well as the pier itself. The ship bunker fuel tanks at the 10th Avenue Marine Terminal, where Arco also has its fuel storage tanks, take a beating from the settling ground and begin to leak.

The settling snaps commercial storage pipelines along the bay like a heavy boot on dry twigs. The quay wall at the North Island Naval Air Station in Coronado gives way, hampering the military’s ability to load and unload supplies. The base will be forced to build a temporary ramp within a day to help out with relief efforts.

At the border, the quake pummels the collection of federal buildings and bridges at the San Ysidro border crossing, where 10 million cars and 35 million people cross every year.

Unreinforced walls throughout the Old Port of Entry Building, built in 1932, fall and other damage in the federal complex will shut it down for repairs from six months to a year.

Outside, the pedestrian walkway spanning the southbound lanes of I-5 sustains heavy damage and will be closed for up to six months. One of the five bridges over either I-5 or Interstate 805 teeters and falls over like a child’s toy, severely hampering traffic for the next five days.

“Many people will be at the border crossing at the time of the earthquake, and some will be injured, depending on the time of day,” the state report says.

Two police stations and four fire stations within 4 miles of the angry fault are slapped into submission, made useless by the structural damage and abandoned.

Emergency Services

Two hospitals within a mile of the Silver Strand rupture, Harbor View Medical Center and Mission Bay Hospital, must be evacuated.

The move means there are 291 fewer hospital beds to take care of the maimed and injured, but it is not considered a significant shortfall. There are more than 1,000 other beds within 2 miles of the fault, 600 of which are in the new Balboa Naval Hospital.

Yet even the unscathed hospitals and clinics are forced to switch to emergency power, some for as long as four days. And many are critically hampered when their complex electronic equipment and laboratory supplies are jolted from shelves and come crashing to the floor.

One facility must be abandoned for two days after its unsecured liquid oxygen tank keels over and explodes.

The trauma centers in Hillcrest, Mercy Hospital and UC San Diego Medical Center are cut off from vehicular traffic because of road damage and rockslides, forcing ambulances to take injured elsewhere.

Most likely, they will go to shelters set up by the Red Cross.

Or they could settle into nearby open-air “prepackaged disaster hospitals” the county has kept in storage since the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Packed into 20-foot trailers, the county has been holding on to 12 of these urban Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, or MASH, units, since they were parceled out by the federal government for civil defense. Each package contains cots, blankets, food supplies and a water chlorinator big enough to supply up to 400 injured people. They are set up in open fields and next to hospitals.

While the command center for local disaster officials, in the sheriff’s communication center at 5555 Overland Ave., is on solid ground, it can’t be used. Construction crews have been ripping it apart as part of a $200,000 project to install heating, air-conditioning and computer lines. The renovation was supposed to be completed by May.

Instead, the county must try to coordinate the massive interagency response out of an old civil defense bunker, partly hidden in the East County hills overlooking Gillespie Field. It will try to maintain contact with County Administrator Norm Hickey, who will be working from an office on Ruffin Road and has been designated under a joint-powers agreement as the local official in charge during a disaster.

Only 25% of their specially designated telephone lines work during the first 24 hours, and officials in the bunker will use their microwave system. The county’s main feelers to the outside world will be cellular telephones and the network of ham radio operators.

Lacking high-tech equipment, Hickey’s aides will be forced to chart the quake’s fury by using stickpins and grease-pencils on large maps. Ironically, they may be working in the dark, since the batteries to the backup generator could be thrown from their unsecured racks.

Their maps will slowly begin to show what experts already expect: The Rose Canyon Fault has created an urban obstacle course.

Transportation

Viewed from the air, I-5 looks like the victim of a savage brawl, its spine twisted and snapped from the border to North County. Hundreds of frantic motorists are sent screaming from their cars, unable to negotiate areas where the pavement has suddenly dropped 2 feet.

At I-5’s intersection with Interstate 15, traffic is halted for two days because of liquefaction under the moorings.

From Palm Avenue on the south to Balboa Avenue on the north, the temblor has twisted the pavement and weakened bridges in several places. Even the abutments that appear undisturbed can be traps, their internal strength sapped.

Visible damage is done to I-5’s crucial interchange with Interstate 8, where liquefied ground has cracked the on-ramps. They will be shut for at least three days.

In Sorrento Valley, the I-5 interchange with Interstate 805 has been weakened to the point that motorists dare not use it. Caltrans crews will be forced to open a small, one-lane detour for no less than three days.

It could also be three days before highway crews can repair the portions of I-5 that have fallen through the squishy earth of North County. There is unpassable settling at the San Dieguito River, the Batiquitos Lagoon, the Agua Hedionda Lagoon and the Buena Vista Lagoon.

The majestic San Diego-Coronado Bridge remains undisturbed over the bay, but it does motorists no good: Settlement, again, has opened a gaping wound in the pavement leading to the structure. Motorists bailing out of Coronado and the North Island Naval Air Station will inch their way along the one open lane of the Silver Strand Highway. Up the coast, sinking lagoons make California 101 useless.

The quake quickly seals off some of San Diego’s best-known places.

Youngsters and their parents who linger at Sea World will be surrounded and cut off when Sea World Drive, Ingraham Street and Mission Bay Drive droop into liquefied soil, unable to be used for at least three days.

Commuters hoping to outsmart the freeways will get no help from the rails.

San Diego trolley service from downtown to the border must be halted for three weeks, because the tracks are bent by extreme settling.

Amtrak trains from Los Angeles to San Diego--the only money-making route in the railway’s national system--are thwarted by rockslides along the coastal bluffs and along the steeply cut railbeds south of Oceanside. It will take at least four days to dig out the debris.

From Mission Bay to the Sante Fe rail station, highly liquefiable fill translates into extensive track “disruption,” knocking out use of the tracks for at least three weeks.

At crowded Lindbergh Field, where more than 11 million airline passengers land ever year on former marshlands, liquefaction also begets transportation meltdown.

Flights are immediately halted because the airport’s lone runway is bowed, maybe cracked. Federal Aviation Administration rules prohibit the use of runways with breaks wider than 3 inches wide.

Lindbergh’s control tower withstands the shocks but loses electrical power. Frenzied air-traffic controllers try to switch on the auxiliary generator but it won’t respond; the unanchored unit was too badly shaken, its starter batteries thrown from their racks.

Since there is no provision for emergency power to the terminals, patrons and employees are on their own, with only corridor and exit lights to help. The baggage conveyors freeze, and computers shut down at the ticket and rental car counters.

The entire eastern terminal and the lower concourse of the newer western terminal take a big hit, since they are built on “spread” footings, the kind that have failed in other recent quakes. There is heavy structural damage.

Outside, Harbor Drive, the only way in and out of the airport, is tilted and cracked. Hundreds of people have no transportation away from the airport.

It will be at least 10 days before the heavily traveled surface street is passable enough to permit repair crews and fuel trucks into Lindbergh. Meanwhile, as many as fifty passenger planes are grounded at the inner-city airport, which will reopen in two weeks, at the earliest.

Emergency supplies and equipment must be diverted to relatively unscathed Miramar Naval Air Station and Brown Field. Even at that, highway damage will make ground access to Brown Field extremely difficult.

Smaller aircraft will have to be diverted to Montgomery Field in Kearney Mesa or Gillespie Field in El Cajon.

Communications and Utilities

Electricity is cut to at least 25% of the homes in San Diego, with the heaviest outages ranging from Mission Bay down to Rosarito in Mexico.

SDG&E;, which has engaged in an aggressive earthquake-proofing campaign, is able to maintain its relatively undisturbed Southwest Power Link and Encina Power Plant, where five units continue to churn out power.

But its South Bay Power Plant in Chula Vista is immobilized for three days when the pipes carrying sea water for cooling and fresh water for steam generation are shorn by the settling earth. It will take more than a week to bring the plant up to speed. Substations built on fill soil will be knocked out and burn, cutting electricity for three days to the areas around Lindbergh Field and up to two weeks throughout the Tijuana River Valley.

Power is knocked out to the 32nd Street Naval Station and won’t be restored for a week.

“Realistically, power is unlikely to be restored to many areas for extended periods of time, possibly up to two weeks,” says the report. The failures will have an unfortunate domino effect, interfering with firefighting, sewage treatment and the water supply.

The Rose Canyon quake also knocks telephones off receivers all over the county.

Within minutes, Pacific Telephone’s main switching facility on 9th Avenue is inundated with calls from relatives, friends and the curious throughout the world. The switches freeze and are out for at least six hours. It will take three days to restore full service, depending on how long harried repair crews can keep up their frantic pace.

The tower at KCBQ in Santee, one of the two stations on the emergency broadcast system, is unaffected but its backup generator is out because it has been nudged from its mooring. The main station, however, is KKLQ in Kearney Mesa, which has links to disaster officials.

San Diegans hoping to learn about the extent of damage must search frantically along the radio dial, since 10 of the area’s AM radio stations are down due to battered buildings, antennas and towers. Television stations suffer the same problems.

Rescuers scattered throughout the area use portable radios for 12 hours, but it is difficult to get through to the sheriff’s command center in Kearney Mesa. The microwave system is working at only 20% capacity. Meanwhile, heavy damage to equipment impairs the use of emergency communication systems in the city’s police headquarters and operations building, both situated near the fault.

As they were in the 1985 Mexico City quake, HAM radio operators are San Diego’s only sustaining link to the outside world. Rehearsal and military coordination allows the informal network of HAM radio buffs to make contact more than half the time.

Throughout the region, there are cries for help because of the numerous fires that burn in neighborhoods from ruptured gas mains and toppled hot water tanks. Most of SDG&E;’s natural gas transmission system survives inland, but major lines along the northern part of the fault are mutilated by liquefaction or landslides.

A major pipeline in Sorrento Valley, rained upon by a slide from Torrey Pines, is out for five days; mains leading to Pacific Beach, Point Loma and downtown are snapped and out of service for at least three days, with complete restoration possible within a week or two.

And those are the lucky ones. Coronado residents lose their pipelines snaking underneath and along the San Diego Bay. They must wait up to four months for gas service to be restored.

The same kind of problems beset the pipelines bringing petroleum products to San Diego. The primary sheath transporting crude from Los Angeles is in for double-trouble at the huge petroleum tank farm just northeast of the stadium in Murphy Canyon. A combination rockslide and liquefaction lead to a booming explosion and to a potentially uncontrollable blaze.

Sewer and Water

The region’s sewage system begins to hemorrhage profusely, spewing untreated human wastes and other effluent from myriad crushed pipes and facilities. The cascade of sewage will head downhill toward San Diego Bay.

On Point Loma, where more than 180 million gallons of sewage a day are treated before being shot out through an ocean outfall, a landslide ruptures the line bringing the effluent directly to the plant. Repair time will be four weeks, during which the sewage will flow unchecked into the open.

A little farther down the line, there is instant devastation at Pump Station 2, situated near Lindbergh Field. The station is responsible for collecting all of the system’s sewage before sending it along to Point Loma. Intake pipes are sheered by the settling, and it will take 45 days to fix them.

A huge sewage tunnel running as deep as 90 feet underneath downtown has the misfortune of crossing the fault itself. It is wrenched open, and a third of the system’s contents are let loose. Fixing it is a massive job and will take at least four months.

The region’s water supply, piped down through two major aqueducts out of Riverside County, is spared by the quake, although one of them will brave potential landslides just north of Lake Murray. Most of San Diego will receive its drinking water.

Except, of course, for the low-lying coastal areas, where two to four pipes will burst per city block. The sudden loss of water pressure makes firefighting futile for at least three days. Parts of La Jolla, Pacific Beach, Ocean Beach and Mission Beach will be without drinking water for at least a month, if not longer. In the meantime, residents will have to boil their water or rely on visiting water trucks.

“For planning purposes, it must be emphasized that the water supply is the single most critical element in the study area,” the draft report says. “The criticality of the problem increases exponentially if the scenario earthquake occurs after a dry year, such as 1978. . . . Restoration of full service could take months.”

Shaking, liquefaction and aftershocks deliver yet another irony to dazed San Diego--the potential that area dams will give way and cover people under walls of stored drinking water.

“The water retained in a large reservoir has enormous potential energy,” says the report. “When released uncontrollably, it can cause extensive loss of life and damage to property downstream. In fact, few activities of man pose greater potential for destruction.”

San Diego has known such sorrow. In January of 1917, a bulging Lower Otay Dam opened “like a pair of giant gates,” sending a flood 20 feet high down the Otay Valley. Despite warnings and evacuation, the flood claimed 30 lives and leveled everything in its way.

Mindful of that, disaster officials immediately dispatch inspectors to the reservoirs closest to the fault. Their quick work reveals fatal weakening of several dams, and the alarm goes out to evacuate major portions of the population in the path of the potential floods.

The largest mobilization takes place downstream of the El Capitan Dam, which in wet times stores nearly 113,000 acre-feet of water. That is enough to supply the needs of 226,000 average families.

Lying in the path of El Capitan are heavily populated areas including four elementary schools, three high schools and two convalescent homes. A torrent unleashed from the sagging dam would wipe out El Monte Road and claim the Las Colinas jail in Santee before heading for the stadium, parts of Mission Valley, Old Town, Sea World and development around Mission Bay. Its victims would include Friars Road, I-805, Mission Gorge Road, Midway Drive, I-5 and California 163.

People are ordered to leave their homes and businesses downstream from an ominous Lake Murray, which adds to the El Capitan flow. The 213-bed Alvarado Hospital Medical Center is immediately in its path.

Other dams that could be of concern include Sweetwater, Savage, Hodges and Wohlford.

By itself, the failure of any single dam would cause its own, special horror story. But in the wake of San Diego’s earthquake, it rates only a chapter in what planners fear will befall the region if the Rose Canyon Fault suddenly comes to life.

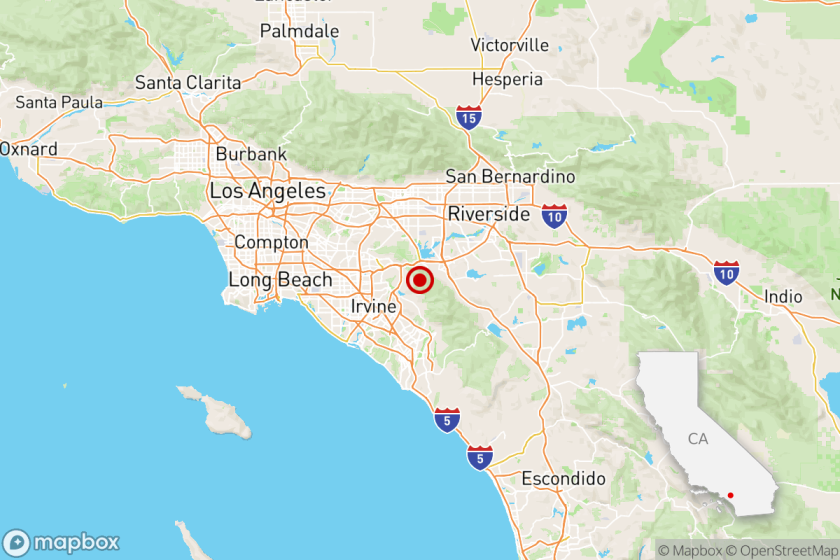

THE FAULT

The Rose Canyon Fault is a series of geological fissures that start in the Pacific off North County and veer through the heart of San Diego before heading back out to sea and along the Mexican coast. The fissures come onto land through La Jolla Cove, hug the eastern edge of Mt. Soledad, run between Old Town and Mission Bay, splay into several fingers around downtown, travel under San Diego Bay, and bisect Coronado Island.

This map is based on a draft copy of an earthquake planning scenario prepared by the Division of Mines and Geology in the California Department of Conservation. The final report will be released next month.

SAN DIEGO BAY

The entire bayfront, including Harbor Island, Shelter Island, Lindbergh Field and much of the downtown waterfront, is built on fill. “Widespread and serious damage anticipated.”

The quay wall north of the B Street Pier will fail, as will the pier.

SEWAGE

1. Pump Station No. 2 handles nearly all of the city’s sewage. The station will suffer serious, long-term damage. The mains leading into the station will be sheared, and they are 36 feet underground. Sewage will run into San Diego Bay. The station will be functionally impaired for about 45 days.

At the Point Loma Wastewater Treatment Plant, landslides are expected to rupture the 108-inch-diameter lines leading into the plant. Sewage will ooze into the ocean. Will take about a month to repair. The sewage tunnel under downtown San Diego will rupture 90 feet underground, and will take four months to repair.

TRAFFIC

2. The I-5/I-8 interchange will suffer heavy liquefaction damage and will be closed at least three days.

On I-5 from Palm Avenue to Balboa Avenue, pavement will be distorted, bridges damaged, hundreds of vehicles trapped and abandoned.

In the lagoon areas of North County, the freeway will settle more than 2 feet.

Bridges at the San Dieguito River, Agua Hedionda Lagoon and Buena Vista Lagoon will not be damaged but the highway will have “severe fill settlement.”

The Coronado Bridge will be closed, not because of damage but because the approaches to it are built on fill and will sink.

The I-5/I-15 interchange will suffer heavy liquefaction damage, though it might reopen in 48 hours.

Harbor Drive, the most heavily traveled surface street in San Diego, will be closed because of liquefaction for 10 days.

AIRPORTS

3. Lindbergh Field will be closed. Large portions of the runway and taxiways are on hydraulic fill and on old marine deposits of depths to 100 feet. Liquefaction is a distinct possibility.

North Island Naval Air Station will have limited operation, but access will be extremely limited because the Coronado Bridge will be inoperable. Limited use is predicted for Montgomery Field, Gillespie Field and Imperial Beach Naval Air Station. Brown Field Municipal Airport, Tijuana International Airport, and Miramar Naval Air Station will be open.

NATURAL GAS LINES

While gas supplies to most of the coastal area will be restored rapidly, some areas could be without gas for as long as several weeks.

4. Pacific Beach, Point Loma, and downtown gas mains will suffer damage due to ground failure. Repair completed in 72 hours. Complete restoration (including relight) completed in one to two weeks.

5. Coronado distribution mains will be damaged due to ground failure beneath and along margins of bay. Coronado could be without natural gas service for two to four months until a new pipeline is installed.

Southern California Gas Co. pipeline at Soledad Valley will be damaged due to liquefaction in Soledad Valley and landslides on Torrey Pines Grade. Shut for an estimated five days.

GASOLINE PIPELINES & STORAGE

6. Murphy Canyon tank farm, northeast of the stadium and operated by Unocal Corp., is on ground subject to liquefaction and landslides from the walls of Murphy Canyon. If there is a fire, “whether the fire can be controlled by oil company personnel is unknown.”

The Navy fuel pipeline will be damaged where it crosses the Mission Bay-Loma Portal area. No hazard, but it will be inoperable for several days to weeks. Also runs through Soledad Valley. The Navy pipeline is connected to the Arco Oil Co. terminal at the 10th Avenue pier, which will be severely damaged, as it is built on artificial fill.

MASS TRANSIT

7. The San Diego Trolley tracks from downtown to the border will be damaged and take three weeks to repair.

The Santa Fe Railway line will be damaged by landslides around Oceanside. The tracks on the eastern end of Mission Bay, through Old Town and near San Diego Bay will be closed for three weeks.

RESERVOIRS

“Likely to be exposed to intense and significantly long-duration shaking.”

The critical period could last 36 hours.

8. Sweetwater Reservoir is upstream from Plaza Bonita shopping center, residential areas, and I-805 and I-5.

9. Lake Murray is upstream from residential areas and Alvarado Medical Center.

El Capitan Reservoir failure would damage four elementary schools, three high schools, a mobile home park, the Las Colinas Jail, most buildings in Mission Valley, San Diego Jack Murphy Stadium, Old Town, Sea World.

Failure of the reservoir at Upper and Lower Otay Lakes would affect Otay Valley agricultural land, some residential areas, and major thoroughfares in Chula Vista, South San Diego, Coronado and Imperial Beach.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.