School classrooms in most California counties won’t open due to coronavirus surge

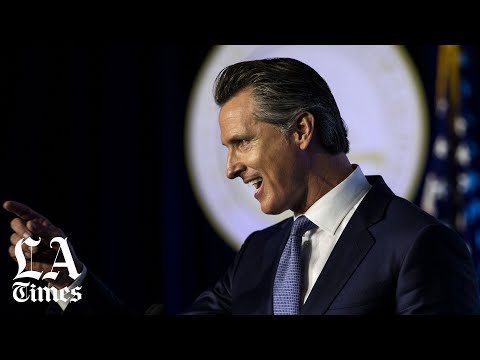

Most California public and private school campuses will not reopen when the academic year begins under statewide rules announced Friday by Gov. Gavin Newsom, shifting instead toward full-time distance learning in response to the summer surge in coronavirus cases.

Schools will remain closed in 32 counties on the state’s COVID-19 monitoring list. Public health conditions in those communities led state officials last week to require a variety of facilities to close, including gyms, shopping malls, hair and nail salons and places of worship. The counties are home to 35.5 million Californians.

“We all prefer in-classroom instructions for all the obvious reasons — social, and emotional foundationally. But only, only if it can be done safely,” Newsom said.

At schools that can open, state officials will require all staff and students in grades three through 12 to wear masks. Younger students will be encouraged to wear masks and students who are unwilling or unable to comply could be asked to switch to remote learning.

The new directives represent state government’s most far-reaching effort to direct the operations of more than 10,500 schools across California during the pandemic. But for at least one-quarter of the state’s 6 million schoolchildren, the mandate only reinforces plans already announced by local officials.

On Monday, leaders of the Los Angeles Unified School District and the San Diego Unified School District announced distance learning for all students returning for the coming year. Other large districts in Southern California, the San Francisco Bay Area and Sacramento also voluntarily agreed to forgo classroom learning because of current health conditions.

Though the practical effect of the Newsom administration’s new mandate is simple, some of the policy’s details are complex. Schools in the counties being monitored for coronavirus spread would not be able to reopen until those counties see at least 14 consecutive days of declining coronavirus cases and are therefore removed from the state’s watch list.

Those schools would be subject to different rules, which will apply in counties with less persistent coronavirus problems. There, the threshold for closing schools is dependent on testing for COVID-19. If a teacher or student in a classroom tests positive, the state will suggest that the class be sent home to self-quarantine.

If multiple classrooms are closed, Newsom said, school officials should close the campus. School districts will be asked to close all campuses if 25% of their locations had enough coronavirus cases to require a shutdown.

The rules for whether schools can open also apply to on-campus after-school programs. And they apply, a state official said, to parochial schools such as those affiliated with the Catholic Church.

Newsom said schools that are allowed to open must, in addition to requiring masks, maintain six feet of physical distancing between students and adults as well as take other health precautions.

“We believe that school days should start with symptom checks, meaning temperature checks,” the governor said. “We have robust expectations around hand-washing stations, sanitation, deep sanitation. Deep disinfection efforts.”

Some education leaders briefed on the proposal questioned whether it is realistic to impose rules that depend on testing when many communities already face a shortage of test kits. The new guidelines also ask for periodic COVID-19 testing at schools.

Newsom’s decision to impose a strict statewide standard comes four days after he suggested the state had already provided ample guidance for schools — a stance that even some of his longtime allies suggested would put students, teachers and school employees at risk while leaving parents and families unsure of what would happen and when.

Last week, the powerful California Teachers Assn. wrote Newsom to say that many schools could not safely reopen under current conditions, — including the lack of sufficient coronavirus testing and personal protective equipment.

Low-income communities, many disproportionately comprising Black and Latino students, face major challenges with distance learning that state and local education officials need to address, community advocates said.

“Things are harder than they were March 16 for our communities ... with the ongoing economic impact of the pandemic and the increase of the spread,” said Maria Brenes, executive director of the East L.A. community organizing nonprofit InnerCity Struggle, and an L.A. Unified parent.

“We’re talking about the essential, the front-line workers that keep our economy going, and this is their children and we’re doing such a grave injustice to them,” she said.

Students with disabilities also face challenges , said Elmer Roldan, executive director of the nonprofit Communities in Schools of Los Angeles, which provides support and case management for about 1,000 L.A. families. Schools need to provide services for students with special needs through distance learning, he said, and must address the existing needs of families who are at a disadvantage with at-home schooling, such as those who speak a different language.

“What do we do to address connectivity issues? Whether it’s the students having a device or having internet that works or having the space where they can do homework? And then what happens when a student needs support that a parent is unable to provide, because a parent may need to work or the parent may be unable to comprehend the lessons that the students are learning?” Roldan said.

L.A. County schools Supt. Debra Duardo said her office is trying to raise funds to address equity and social-emotional needs “so that students and families are able to succeed in a remote learning environment.”

The state also updated its guidance Friday for day-care centers, which will be allowed to remain open but must investigate whether work-related factors contribute to any outbreaks and implement preventive measures accordingly. The new guidance requires day-care centers to provide training for staff and families on personal hygiene and the “proper use, removal and washing of face coverings.”

Previous day-care recommendations include face coverings for staff and for children 2 and older, and health screenings of children and staff before they enter a facility.

Whether school districts are able to fully cover the costs of expanded distance learning remains unclear. The state budget signed by Newsom last month commits $5.3 billion for school needs linked to the pandemic, most of that from the federal relief package enacted in the spring. More than half the money will be allocated to schools based on the number of children who are English learners or come from low-income families.

That amount of money will help and is more than some states have to work with, said Elisha Smith Arrillaga, executive director of Education Trust-West.

“But especially with the announcement that we’re in this for the long haul for long-distance learning, we really need the resources to be able to implement it well and equitably across the whole state,” she said.

Even then, K-12 schools will find their resources stretched. The state budget spreads out the payment of some $13 billion in school funding obligations, to be covered in the short term by local cash reserves or by the school districts borrowing money. Districts have also worried about language tucked into the final budget that seems to require some level of in-person schooling, though lawmakers later insisted that would not prevent public health requirements from completely closing campuses.

Before Friday’s announcement, the new school year seemed to be starting much as the last one had ended — with local officials making their own decisions, on their own timetables. Despite calls for statewide action, Newsom avoided a blanket policy dictating when to close schools as the virus spread throughout the state in the early spring.

The governor, who has four young children, chose instead to approach the issue as a parent, telling reporters in mid-March that he told his daughter that schools probably wouldn’t reopen at the time — framing the comment as a reality check, not a directive from his office.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.