Working Hollywood: Writers are the ‘labor’ and ‘leprechauns’ behind TV’s latest Golden Age

There wasn’t much pain in suburbia, but there was enough boredom to set loose a boy’s imagination and send him toward “Monty Python,” Woody Allen, “Saturday Night Live” and the expanding universe of science-fiction. Add Norman Lear, a bit of David Foster Wallace and that boy ends up in Hollywood, writing a sitcom about death and the afterlife.

The roads and whispers that lead aspiring writers to Los Angeles are many, but for Michael Schur, whose credits include “The Good Place” and “Parks and Recreation,” it began trying to make his teenage friends laugh in West Hartford, Conn. Or disappearing into intergalactic movies like “Dune,” which he said “blew my mind because it was such a gigantic world.”

The life Schur and thousands like him have chosen has been re-imagined by streaming, multiple platforms and cultural and aesthetic shifts that have given TV writers and showrunners enormous creative reign. More so than their counterparts in film, where directors still rule, television writers are the scribes of the age, intuitive voices that sense our demons and desires and give us stories that range from the Machiavellian darkness of “House of Cards” to raucous humor of “Brooklyn Nine-Nine.”

The contract reached recently between the studios and the Writers Guild of America avoided a strike that would have paralyzed TV’s new renaissance. But the negotiations highlighted the indistinct terrain between art and commerce, where the romantic ideals of the writer collide with stock indexes and profit portfolios. It has been that way since F. Scott Fitzgerald and William Faulkner wandered here nearly a century ago to drink, toil in bungalows and turn prose into pictures.

The strains between the talent and the money remain prevalent. Marti Noxon, creator of “Girlfriends’ Guide to Divorce,” likened an “executive’s job at one of the television studios as one of trying to figure out how to train leprechauns. They have no idea how to get the desired result. They know procedurally how to get them, but the creativity and mystery of what makes something good is as elusive as ever.”

In a country where unions have lost most of their clout, the WGA remains a powerhouse. It won its nearly 13,000 members increased TV residuals and protected broad health-care benefits. The average TV writer earned about $200,000 in 2015, according to the WGA’s latest annual report. That number was skewed by a small class of writers and showrunners at the top who earn millions. Many in the guild make much less.

While streaming services have exponentially increased opportunities, the days of the long-running network series’ — and their inherent residuals — are dwindling. Writers often cycle from series work to unemployment and back.

“Writers are hesitant to consider ourselves labor because it seems insane, right? We’re not digging ditches. We’re not building roads. We’re writing jokes or words for a living,” said Schur. “It feels very embarrassing to think of ourselves as a labor force. But in our little world that’s what we are. We’re labor and they’re management.”

The cliché about Hollywood “is that it lives in a world apart from the cultural and socioeconomic winds of the rest of the country,” said John Eisendrath, a television writer and executive producer of “The Blacklist.” “But I do think this is an example where it seems like it is in lockstep with what happens in the rest of the country, where capital is what the economy is prejudiced toward, invests in and rewards, and labor is not invested in and isn’t getting the benefits as much as in the past.”

“We’re dealing with a bunch of vampires who can’t be outside during the daytime.”

— Carina Adly MacKenzie, writer “The Originals”

That of course is a relativity parsed in degrees. And, at times, gender.

Female TV writers have made progress in recent years but lag behind men. Women earned about 93 cents for every dollar a white male writer made in 2014. The “2017 Hollywood Diversity Report” by the Ralph J. Bunche Center for African American Studies at UCLA found that women were the creators behind 20.9% of scripted cable shows. They accounted for 20.4% of scripted streaming shows, such as Jill Soloway’s “Transparent,” a 5% jump from 2013-14.

But every writer can point to that moment of epiphany. Schur and Eisendrath, who ventured into TV land in the 1980s with the exercise show “Body by Jake,” are established talents influenced by an earlier Golden Age that included “All in the Family” and “The Jeffersons.” Newcomers like Carina Adly MacKenzie, who grew up watching “Dawson’s Creek” and deciphering the hyperbolic dialogue of Aaron Sorkin, started as a writer’s assistant a few years ago taking home about $600 a week.

“Writers are up against scheduling and budgets and actors who have other obligations,” said MacKenzie, now a writer and producer on the vampire series “The Originals.” “We create a script but there are a million reasons that particular script won’t work. So much of my job is to be a troubleshooter. When the producer calls and says: ‘We’re not going to be able to have this many night shoots. We need to move night later on the episode.’ But we’re dealing with a bunch of vampires who can’t be outside during the daytime.”

The possibilities for a writer to send in a spec script and hopefully — often delusionally — wait for his or her phone to ring, like in the old days, are slim. “You have to have a connection or be promoted internally,” said MacKenzie, who once wrote for The Times. “People don’t want to read spec scripts anymore. TV is an incredibly collaborative medium” that includes the writer’s involvement in camera shots, wardrobe and props.

Eisendrath was working as a journalist for the Washington Monthly in the 1980s when he was struck by the cop drama “Hill Street Blues.” Co-created and written by Steven Bochco, the show foreshadowed how TV would creatively evolve into shows like “The Wire” and “The Sopranos.” Eisendrath said he looked at the credits and “saw that a writer is in charge of all this. That was incredible to me. It inspired me to come out here and try my hand.”

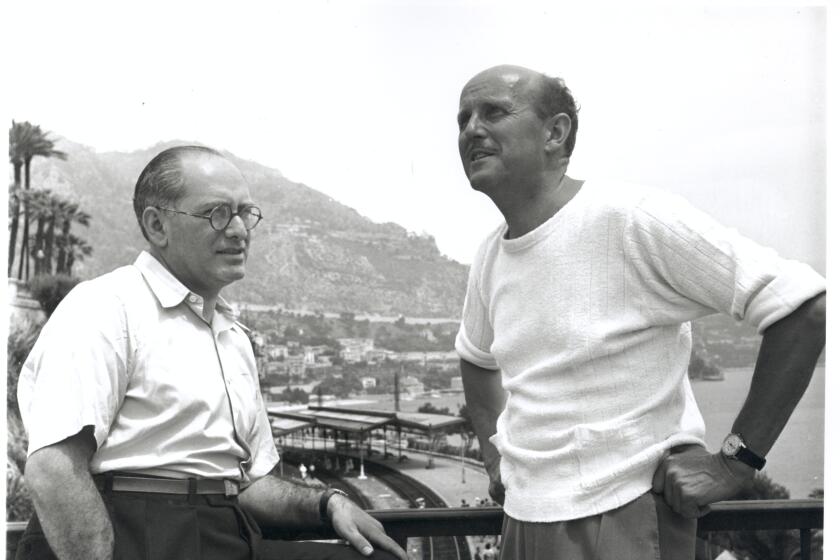

He wrote a series about TV news called “WIOU,” which brought him into the orbit of Grant Tinker, head of MTM Enterprises, an influential independent production company that developed “Hill Street Blues” in an era before the studios were bought by corporations and the industry consolidated. Eisendrath went on to write and produce for “Beverly Hills 90210,” “Alias” and “The Blacklist” starring James Spader, an internationally roving criminal who leads the FBI to terrorists, black marketers and serial killers.

“One of the greatest gifts to writers in the last 40 years in TV was Grant Tinker,” said Eisendrath. “He was a singular figure in the lives of writers then and a shadowing presence over writers today, most of whom don’t even know who he was. He was that rare executive who stepped back and promoted the writer. He created the environment for the showrunner we know today.”

Much has changed since Tinker’s day. Back then, said Eisendrath, streaming and multiplatforms were in the future and a show receiving a 23% market share was a disappointment. “Now you get 3% of the people and everybody’s thrilled,” he said.

The pace once production starts is frenetic; a script is produced every eight days, and shows like “The Blacklist” draw writers from different genres to tap out plots, subplots and back stories.

“It’s like writing a novel,” he said. “You’re letting each episode get unpacked and unfolded in certain ways that hopefully can surprise you and take you in unexpected directions.”

Noxon has made a career out of the unexpected and, she said, “not to just grow where I was planted.” A child of Los Angeles, Noxon, whose filmmaker father told her he took care of the MGM lion, is a creator and writer whose credits include “Buffy the Vampire Slayer,” “Mad Men,” “UnREAL” and the upcoming “Sharp Objects” for HBO. Despite her success, she has found that the writer’s life is one of gaps, risks and doubts.

“It’s been only recently that I’ve started to feel like, ‘Yeah I’m probably going to be allowed to keep doing this,’ ” said Noxon, whose themes often center on women in challenging predicaments. “It took years of getting jobs and another job and the next job. You go from one circus tent to the next. You’re constantly wondering how long it’s going to last and how long will you play this town.”

Much of TV’s current golden age, she said, is propelled by cable and streaming services that “allow what’s going to be provocative. Whose stories haven’t we told?”

When it comes to scripts, Schur, who like Noxon is among the industry’s more insightful writers, is a talker, needing to bounce phrases and ideas off others. “A blank page almost every writer will tell you is the scariest part of the job so I try not to do it until I’ve talked out loud with other people,” he said. “Sitting in a room is really hard. You’re trapped inside your own brain. But accessing other people’s brains helps a great deal.”

Such banter was prevalent in his early days as a writer for “Saturday Night Live.” Since then Schur, who wrote for “The Office” and was an executive producer on Aziz Ansari’s “Master of None,” has explored the existential and the afterlife in “The Good Place,” a comedy that would likely have intrigued David Foster Wallace, one of his favorite novelists.

Schur said these days in TV “in terms of your imagination there’s no idea that’s too insane or outlandish that won’t at least get considered. You have shows dealing with every aspect of society. Politics, race, gender. ‘Transparent’ wins Emmys. That’s incredible. The transgender community wasn’t represented at all in the entire landscape of entertainment for years, for its entire history, and now suddenly is a gigantic hit.”

The new television landscape has created targeted universes for viewers and writers, allowing each to pick and disappear into genres and specifics from superhero to murder mysteries. “It’s incredibly tailored to your interest and type of experience. The question is whether that’s homogenizing in its own weird way,” said Noxon. “You can take a constant diet of whatever genre you’re fascinated by. It’s becoming so tailored that sometimes I wonder whether you have to try something new.

“I’m always trying a new experience. That’s why I haven’t burned out, I think.”

See the most-read stories this hour »

Twitter: @JeffreyLAT

ALSO

Acting teacher Elizabeth Mestnik wants to know what you would die for, and please no phony tears

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.